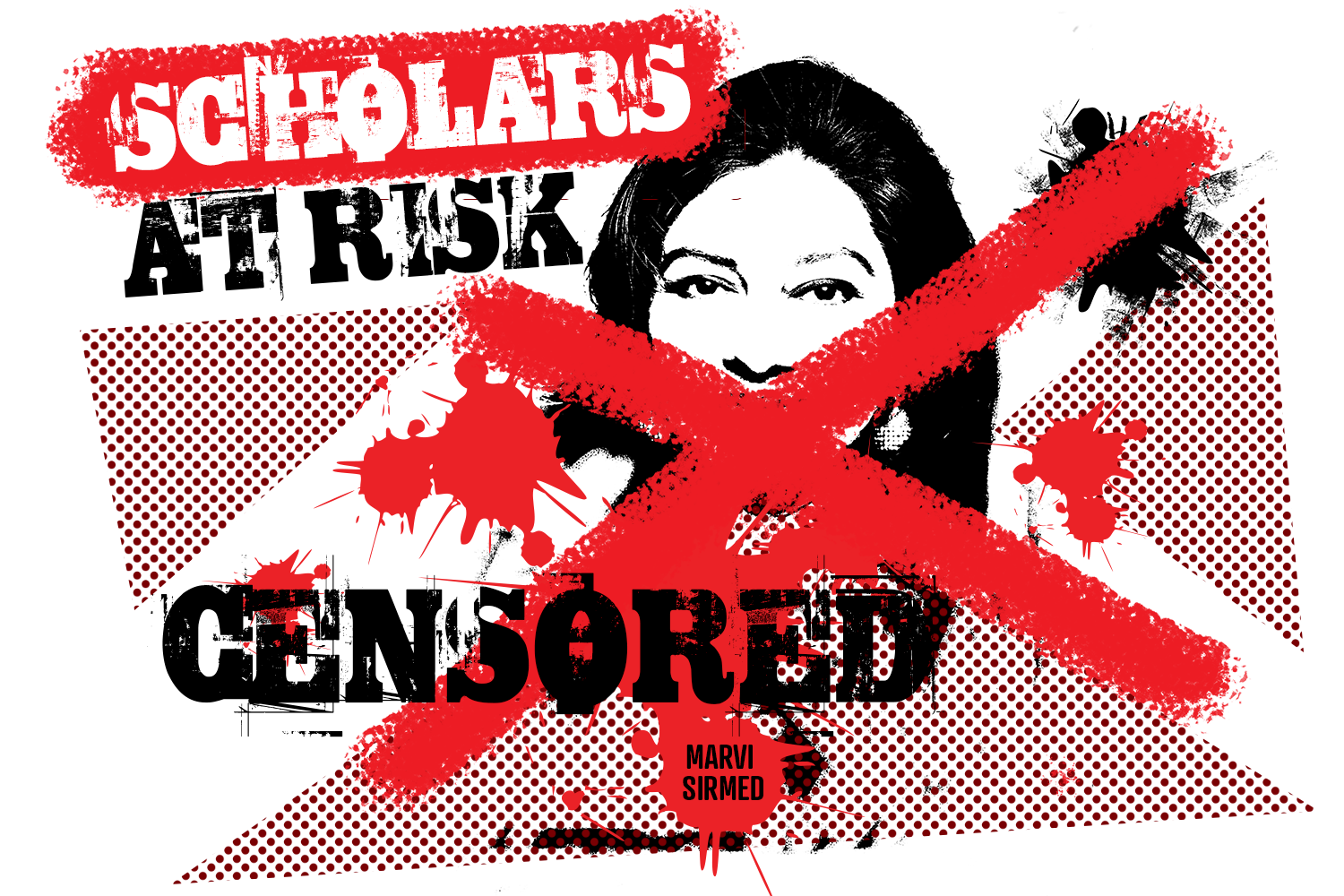

"There was suddenly a fatwa on my head"

For reporting on terrorism, extremism, and atrocities against women in her country, Marvi Sirmed found herself under the most serious of death threats and escaped an assassination attempt. The Pakistani journalist found the freedom to live — and to work and teach — at UConn.

By Jaclyn M. Severance

Illustrations by Sean Flynn

In 1991 in Pakistan, there was a surge of women being burned.

A stove would burst, the official report would say — a terrible accident — and only the young bride of the family would be injured or, more often, killed.

"It was very intriguing for me," says Marvi Sirmed, a journalist and activist who was one of the rare young women working at a newspaper in Pakistan at the time.

"When I started digging, first they said, 'Oh, you know, because in the kitchen, only the daughter-in-law works, so everyone else remains unhurt.'"

Most newspapers in Pakistan at that time employed only one woman, says Sirmed, and that woman was known as the "lady reporter," who would exclusively write for women.

Articles about the latest fashions or recipes or romantic short stories were the sorts of topics that women in the patriarchal society should be reading, according to the men who ran the newspapers.

Sirmed, who was working as the editor of her newspaper's weekly women's edition, felt otherwise. "I kept digging for four or five months for this story, and some of these incidents would be accidental," she says, "but most of it was because the daughter-in-law did not bring enough dowry. So, it was a dowry killing, or an honor killing, concealed into accident."

Her enterprising journalism was not welcomed.

"I brought several stories of the survivors of these 'accidents,' and my editor just refused to entertain that," she says. "He said that women buy the women's edition because they want to read more about the pleasant subjects. But what you are doing is exactly what they don't want to know and what we don't want to put in our publication, because these are not pretty faces. If you want to do a modeling session with a high-ranking model girl who would display good apparel, we are all for it. But these faces of burned women, it's absolutely a 'no' story."

The stories of the burned women were far from the last time Sirmed would face opposition, controversy, harassment, personal attacks, and outright violence for the stories she wanted to tell and the light she aimed to shine on some of the darkest corners of Pakistani life and governance.

In fact, she's still telling those stories and working as an activist for change in Pakistan and other South Asian countries, though she's now more than 7,000 miles away from her home country, in the United States — teaching at UConn through the University's longstanding and unique partnership with the international network Scholars at Risk.

A Network to Safety

"It's at the very heart of a university's mission to advance knowledge and to advocate for academic freedom," says Kathryn Libal, an associate professor of social work and human rights at the UConn School of Social Work and the director of UConn's Human Rights Institute (HRI).

Since November 2010, UConn and HRI have worked to help support that mission as part of the Scholars at Risk Network, or SAR. Established in 2000, SAR assists academics who face persecution by arranging short-term positions for them at host universities around the globe.

"The scholars hosted through SAR represent all disciplines," explains Libal, a champion of the network who also serves on the organization's steering committee for the U.S.

"They might be physicists. They might be political scientists. They might be molecular cell biologists. And in their home countries, they are persecuted because of their research or teaching. SAR is a global institutional response that supports scholars and practitioners so that they have the freedom to think and exchange knowledge."

Since becoming a part of the network, UConn has hosted scholars from Mexico, Iran, Syria, Ethiopia, Turkey, Nicaragua, and now Pakistan. They can stay two years or more, which gives them time to address a number of unmet needs, while gaining their bearings in a safe place.

"It's not just about having a scholar figure out how to write for U.S. journals," says Libal. "Many haven't had access to good health care for some time. Some have experienced trauma and have latent health challenges. So having a couple of years to address health needs is really critical."

UConn can offer this support to its SAR scholars, Libal says, because the entire University community — from the president and provost to the faculty and students — has embraced the network's mission and goals, and has put the structure and resources in place to make the program successful. "UConn is deeply committed to our human rights mission, with this program serving as a powerful example of the impact we can have," says provost Carl Lejuez.

UConn is one of the most active and committed hosts of SAR scholars in the country, says Rose Anderson, SAR's director of protection services. "We have frequently asked UConn to participate in workshops for SAR hosts and scholars to impart their perspective on host support needed for a visit to be as successful as possible," Anderson says. "In this way, UConn inspires other campuses to become involved."

With some 550 members in 42 countries, the SAR network each year places more than 100 at-risk scholars. An increasingly high demand forces SAR to focus its efforts on scholars facing the most immediate and severe threats, including threats of violence, torture, and wrongful imprisonment or prosecution — scholars just like Marvi Sirmed.

When the Threats Come

When, as a budding journalist, Sirmed asked to start reporting on politics, she was harassed by the male reporters who worked in the newsroom.

"It was very difficult, because if you are sitting in the newsroom with all the male reporters, they would be 100 percent sure that you are making yourself available for them, and you are fair game," Sirmed says. "Sexual harassment was not even a word back then. It was considered a fact of life that a woman has to endure — to tolerate harassment — if a woman decides to move out of the four walls of the house."

Sirmed left reporting and started working as a columnist, because it didn't require her to go to a newsroom — she could instead work on her stories on her own time. She spent the next 20 years working as a columnist, often writing about political issues and terrorist organizations and advocating against human rights abuses in Pakistan.

She also worked for the United Nations Development Program in Pakistan as an expert on democracy and parliamentary institutions. And while she says the U.N. was supportive, Sirmed's outspoken activism did not earn her many friends from within the Pakistani government, the military establishment, or the active extremist groups in the country.

In 2012, Sirmed survived an assassination attempt, when unidentified gunmen fired several shots at her and her husband, Sirmed Manzoor, who also is an investigative journalist, in the capital city of Islamabad. They were unharmed.

"That was one point in time where we seriously considered leaving Pakistan," she says. "But we did not. Even at that time, we did not."

She did ultimately leave her position at the U.N. and began working as a consultant, offering research and writing services to international organizations and using any profits to support victims of terrorism, especially women.

"There were very many destitute women who were left because of the terrorism in Pakistan," she says. "For lack of education, skills, and job opportunities, many of them were pushed to abject poverty or were left at the mercy of the extended family —when they were not opting for suicide."

And Sirmed kept writing. In 2017, she began working as a special senior correspondent for the Daily Times, an English-language newspaper, covering topics such as human rights, violent extremism, and terrorism in Pakistan.

"That was a hard area to report for women reporters," she says. "Women had started reporting on politics, but terrorism was an area that was considered a male domain. Reporting on that area makes many enemies, and that's where I made my very strong enemy of the Taliban."

Her home was ransacked multiple times with computers, passports, and other personal items taken. She was publicly slut-shamed while simultaneously being called an angry, sexless feminist. Threats were made against her family, including her young daughter. Her personal phone number and email were posted online, leading to harassing and threatening messages. Personal details about her family members, including her parents, were also distributed online, alongside calls for them to be attacked.

"They were not only threatening my life, they were attacking my integrity," she says. "Living in Pakistan and working as a journalist and an activist was a continuous trauma."

Threats were also made against the publications that she wrote for. Sirmed began to self-censor what she published in the newspaper, she says, out of fear of what might happen to others within the organization.

"When the threats come, it's not just you," she says. "It's not about you always. It's about so many other people, and you feel responsible. If there is an attack on you, it's still a concern. But if there is an attack on someone else because of you, that's something so torturous that you can never live with yourself."

"Learning that lives with you."

Jarred Riel '24 (CLAS), a double major in human rights and human development and family sciences, was one of the students in a human rights class co-taught by Marvi Sirmed and Kathy Libal.Â

"It was Marvi who drew me to that course," Riel says. "I read her story, and it was just so captivating, what she had been through and all the accomplishments she had, but also what she was facing in Pakistan. That she would be teaching this course — I thought it would be something that, honestly, I wasn't ever going to get an opportunity again to have this type of experience with a professor."Â

What is the national origin, demographic and academic background data for SAR scholars. The article is interesting but only a sample of 1 and, accordingly, is not very informative.

Please see the links below the story for more information on the SAR program.