I Wouldn't Have Listened to Me

The I-84 musings of famed sportswriter Leigh Montville '65 (CLAS)

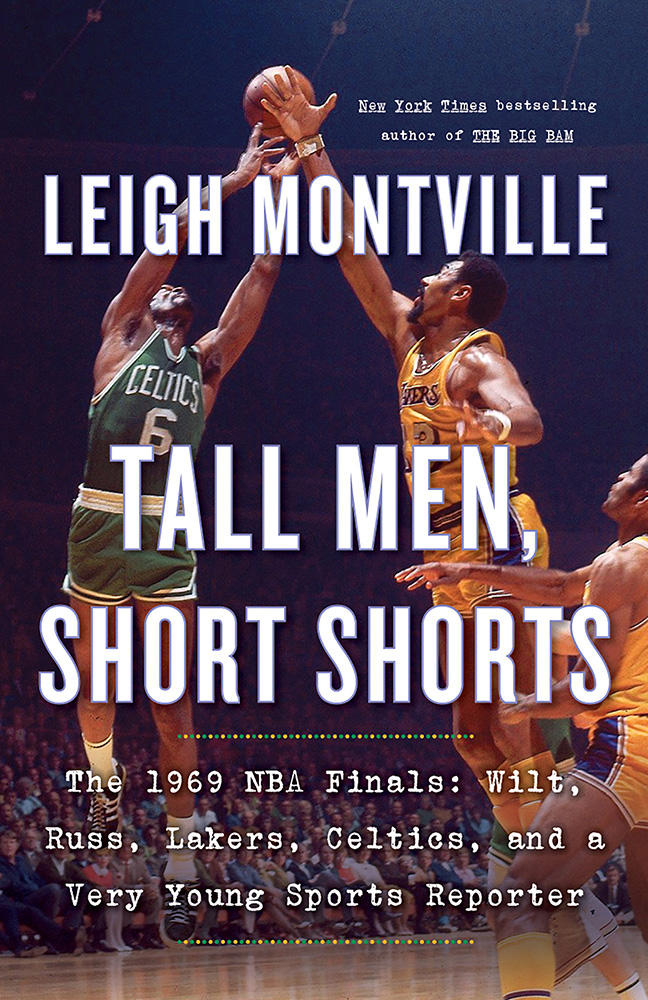

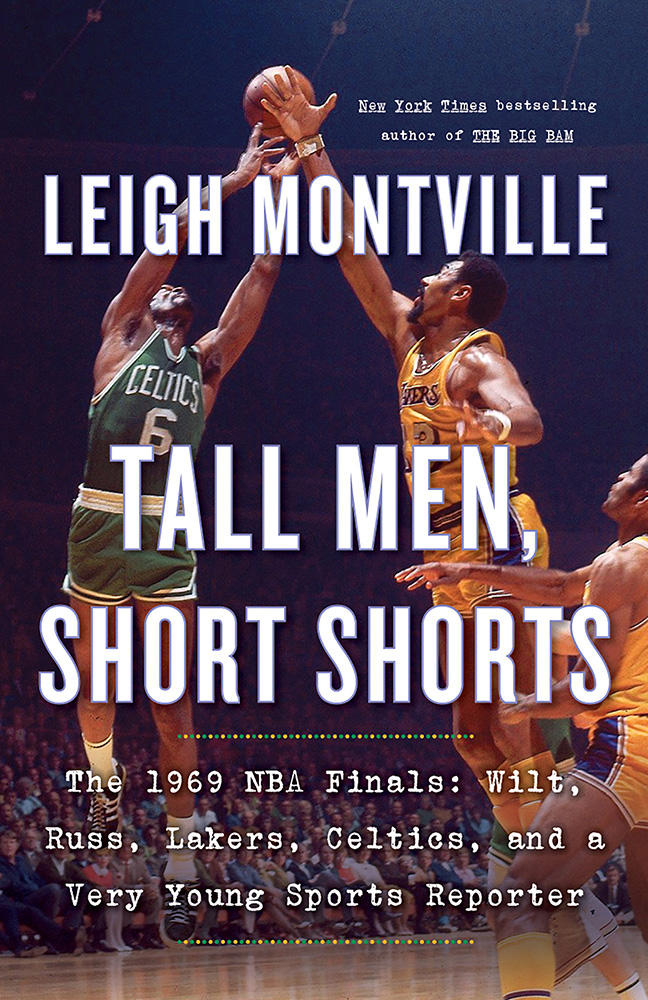

Montville in his Medfield, Massachusetts, home office in April. His latest bestseller chronicles the story of both the '69 Celtics versus Lakers series and the jumpstart of his own now-legendary writing career with the Boston Globe.

The thought arrived on that mindless stretch of I-84 between Boston and Storrs. You know where I mean. You're heading past what once was RedArt's garage on the right, then a sign for the Ashford Motel, then the Ruby Road turnoff for the TA Truck Stop in Willington, then the billboard for exotic dancing at the Electric Blue Café, all in preparation for Exit 68 and that seven-mile straight shot on Route 195 back in time to the UConn campus you once knew so well.

"Will these kids pay any attention to me?" I wondered.

I was scheduled to speak to Mike Stanton's Newswriting I class in a lecture hall in the Nursing School in an hour or so, describing a career as a sports columnist at the Boston Globe, a senior writer at Sports Illustrated, and as the author of nine books, plus a tenth that I had just started. I certainly had enough experience to talk, but maybe I had too much experience.

You know what I mean.

I graduated in 1965. This was 2019. The difference was 54 years. Suppose some character showed up in the office of the Connecticut Daily Campus at the Student Union in 1965, some wizened graduate from 54 years earlier, ready to impart some journalistic knowledge to the young editor-in-chief. The visitor would have graduated in 1911. Would I have paid any attention to someone who graduated in 1911?

"Not a chance," I decided.

Would these kids pay any attention to me?

Born in 1943, I always have considered myself as being in the first shock wave of the baby boomer generation. We, as a group, always have thought we were eternally young, eternally cool and up-to-date. Hip. (A word that, when used today, translates as un-hip.) This new thought about the 54-year age difference, about the visitor from 1911, was an unsettling reminder of the effects of growing older.

There is a point, somewhere around a person's 65th birthday and certainly above, where describing how it is becomes describing how it was. Technology moves along on its own impatient clock. Relevance is switched into stories, history. What was new, alas, has become old.

The names on buildings, for instance, become people from your past. Homer Babbidge is not the president of the University, the well-dressed and smooth, dignified, Yale roommate of New York mayor John Lindsay and actor James Whitmore — he is the name of the school library. Don McCullough is not the pleasant guy running the Student Union. There is a plaque remembering him in the Student Union. The Daily Campus has an entire building of its own. Has had it for years. The Field House was where the basketball team played? When was that? There was no women's basketball team? There were no women's sports? None? [True! There were no varsity women's sports from 1938 to 1974.] "Tall Men, Short Shorts" is the book I had just begun when I made that visit to the journalism class in 2019. The subtitle is "The 1969 NBA Finals: Wilt, Russ, Lakers, Celtics, and a Very Young Sports Reporter." The very young sports reporter is me.

I look at myself, four years out from UConn, 25 years old, covering this transcontinental series of seven games between the Boston Celtics and Los Angeles Lakers for the Boston Globe. I am interviewing Bill Russell and Wilt Chamberlain, tall and talented men I had watched not much earlier on a black-and-white television in the lounge at the Phi Sigma Kappa house in the fraternity quadrangle. (There is no fraternity quadrangle any more? There is no Phi Sigma Kappa?) I had never been to California, never seen the Pacific Ocean, never traveled on a plane long enough to see an in-flight movie. Now I am flying to California and back three times in two weeks. The in-flight movie is "Bullitt."

I use a typewriter, an Olivetti Lettera 32, the one all reporters use. I send my stories back to Boston by Western Union. I call on a pay phone to see if my stories have arrived. There are no cellphones. They have not been invented. There is no Twitter, no Facebook, no social media at all. The interviews are conversations, not staged events with an ad for some bank in the background. Only two of the seven games are on television in Boston, only three in LA. The written word is king. The delivery of a newspaper is an important daily event.

The world is so different. I watch my young self bound through it all. I wince at his combination of great confidence and greater naivete. Turn back the clock to then and I would have great tips, great advice to a journalism class at the University of Connecticut.

Now?

I try to tell some of it, tell the stories, try to capture the romance of that time. There are maybe 60 kids spread out in lecture-hall tiers in front of me. Each kid has a computer open. Some are typing. Maybe they are taking notes on what I say. Maybe they are playing Donkey Kong. Hard to tell. I do my hour, answer a few questions at the end. The kids head off to their next class. I head back to Boston.

It was all OK.

It was fine.

Says the visitor from 1911.

By Leigh Montville '65 (CLAS)

Photo by Peter Morenus

Good morning, Lisa.

I enjoyed the most recent edition of UConn Magazine, especially Leigh Montville’s piece.

The visitor from 1911, Leigh Montville, still has much to teach us… and not just about journalism from a bygone era. He shows us how to give back, to share his time and talent with UConn students – as he did with me in 1975 when I was editor in chief of The Daily Campus. Montville’s mentoring ways are reminiscent of those of Wallace Moreland ’26, a former editor in chief of the Connecticut Campus and my own visitor from a bygone era. Thankfully, this kid listened.”

— Arthur M. Horwitz ’76 CLAS