Walk This Way

An alum and Guggenheim Fellow whose art is about nature, adventure — and sneakers

By Jackie Fitzpatrick Hennessey '83 (CLAS)

Photos by Matthew López-Jensen '08 MFA

T

he first thing Matthew López-Jensen '08 MFA needs is a pair of shoes. Not just any shoes, but shoes for climbing fences, tromping in and around marshes, and walking 20 miles. He laces up his latest pair of New Balance sneakers, grabs his camera, notebook, and a backpack and sets out.

The first thing Matthew López-Jensen '08 MFA needs is a pair of shoes. Not just any shoes, but shoes for climbing fences, tromping in and around marshes, and walking 20 miles. He laces up his latest pair of New Balance sneakers, grabs his camera, notebook, and a backpack and sets out.

López-Jensen speaking to participants on Collecting SoHo artist walk, 2013.

That is how, at the beginning of the pandemic, you'd find López-Jensen. He had been asked by Mary Miss, the director of City as Living Laboratory — a nonprofit that works with artists, scientists, and residents of urban communities to find solutions to environmental issues — to create a virtual walk along Tibbetts Brook. So he followed the brook from the Bronx to Yonkers, mapping out a path that could serve as an online respite for people stuck indoors.

"I ended up in a field of marsh marigolds, and it's swampy, and there are no planes overhead because it's in the middle of Covid, so it's super quiet," he says. "A great blue heron emerges out of the grass up ahead, and it flies off, and I'm sitting there by this little muddy trickle of a stream in the middle of what feels like nowhere, but it's the middle of New York City. I have versions of that experience in almost every landscape. It's quiet. I'm alone, and nature's being nature, and it's wonderful."

A Guggenheim Fellow, López-Jensen is an "interdisciplinary lens-based artist" whose pieces are part of the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Brooklyn Museum of Art, the New York Public Library, and the Center for Fine Art Photography. His projects have received National Endowment of the Arts funding.

He takes photographs and gathers into artful bundles the flora he finds along Brooklyn's Flatbush Avenue or the banks of a winding river — common mullein, ragweed, couch grass, sycamore, or seaweed, entwined with treasures he's discovered. One such treasure, a porcelain cane topper in the form of dice from the 1920s is "sort of symbolic for walking and chance," he says. "I'm trying to build a subtle portrait of a place with objects and plants."

As much as he loves exploring, he also loves research. "I try to learn about the folk histories, medicinal uses, and ecological realities surrounding the plants and trees that feature in my work," he says. "I'm always reading one natural history or another. Every tree has its own book or books. And every weed cures something."

The Bronx-based artist tells the story of a landscape in words, photos, video, and found-art sculptures. He also makes extensively detailed maps, thousands of which have been available at museums and parks for people to use on their own walks. It all "begins with looking," he says. He searches for beauty in seemingly inelegant or even destroyed places. "And I always find it."

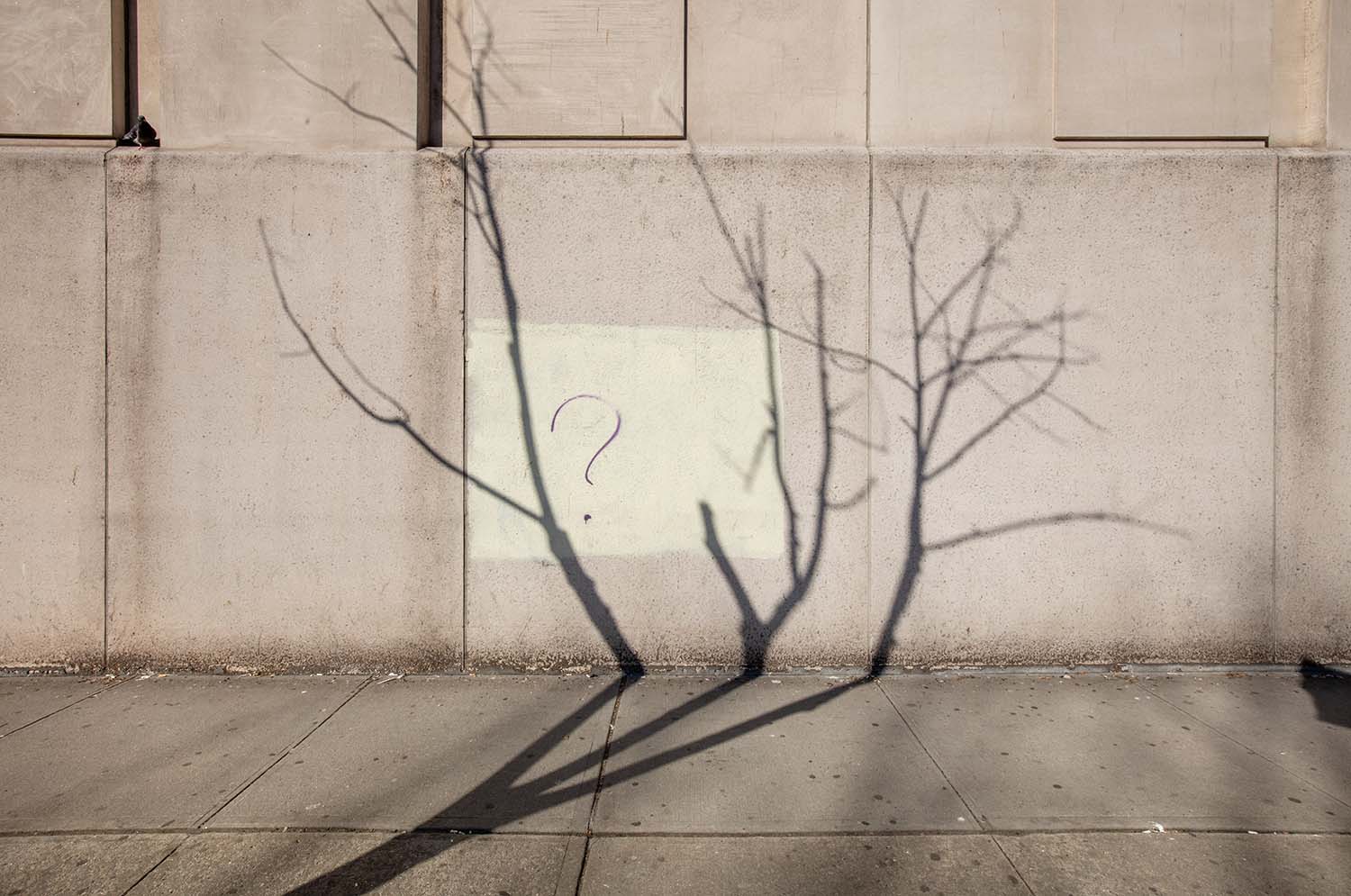

Shadow of a Dead Street Tree, Chelsea, Manhattan, from Tree Love series, 2020.

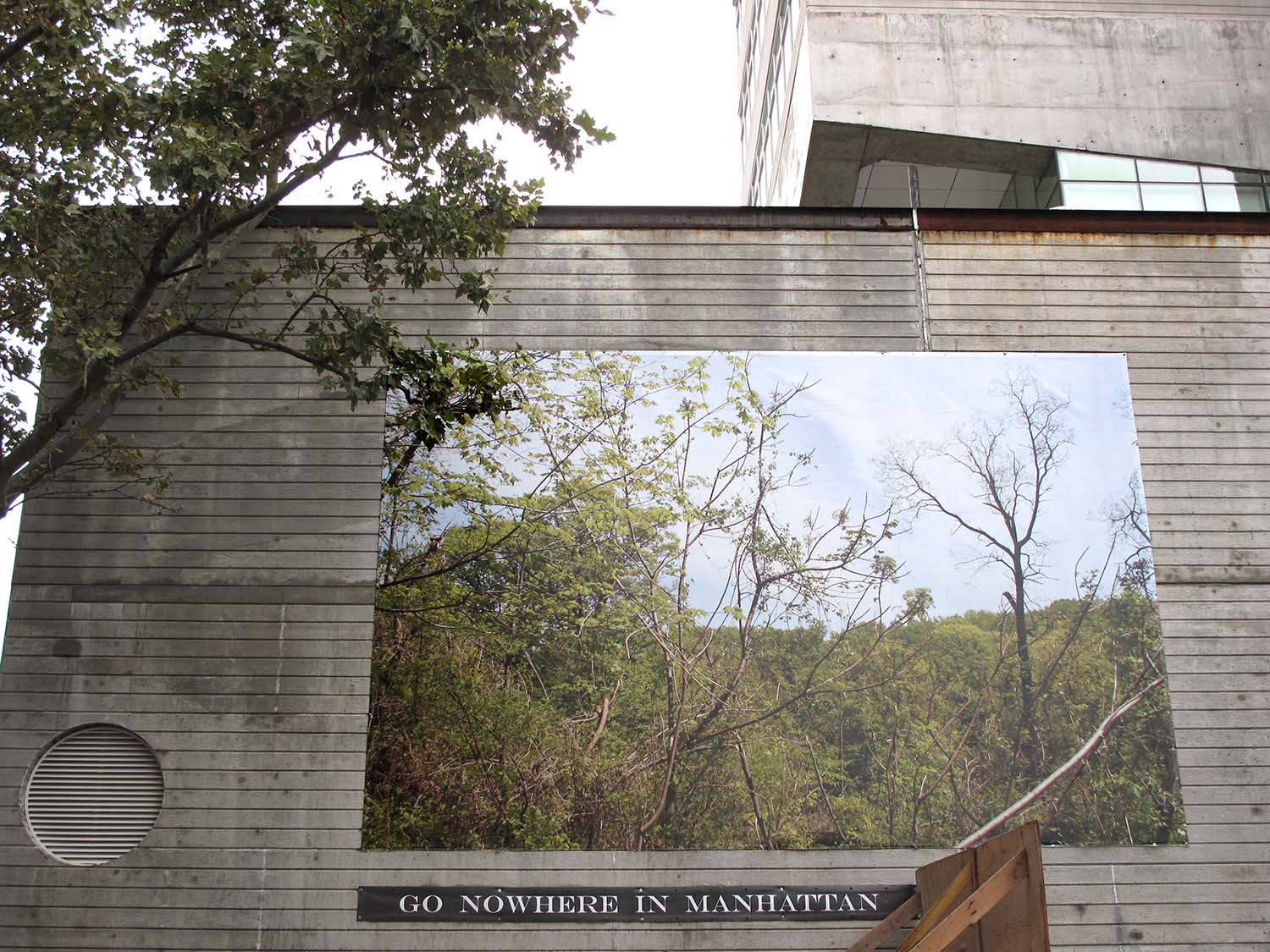

Inwood Vista from Nowhere in Manhattan series, installed as a 26-foot-wide billboard on Thompson Street in SoHo in 2010. (The work is still installed, but the color has faded).

A Tree Climbing Kid

He's had this spirit since he was young. Sugar maples, white oaks, spindly tall trees in the woods — how high could he climb? How far could he see into the world? Those were his summer days, as seen here trimming a yew at age 11. "I spent all my time back in the woods, up in the trees," López- Jensen says. "I was good at climbing, and I liked heights, so I was a bit of an adrenaline junkie. If I found the right spot in a tree, I could read a book or bounce around or just look out."

As luck would have it, Killingly High School had a photography program with "a photo professor who knew his stuff and fought for funding." López- Jensen bought a 35-millimeter camera he could afford and took every class he could. "I was always in the darkroom," he says. He walked around Killingly and surrounding towns, stopping to explore and take photos of old, abandoned mills and barns.

"It was what I would end up doing for the next 20 years, focusing on the place where nature and the history of the landscape collide," he says.

Still, during undergrad at Rice University in Houston, Texas, he wasn't ready to believe that art could become his career. "When you grow up in a certain realm without an exposure to art, the idea of being an artist doesn't exist, so I thought 'I'll major in photography — which I love — and political science — where I'll get my job.' I didn't know how to make money or survive as a photographer or an artist."

After graduating, he worked for about five years on political campaigns, which eventually took him to New York City. He was about to pursue a master's in public policy, "When I said, 'Wait a minute.'" Instead, he decided to work on his photography portfolio, applied to MFA programs, and chose UConn.

Shadow of a Man and a Honey Locust, Norwood, Bronx, from Tree Love series, 2020.

Becoming an Artist

He had space at UConn — two whole studios — and time to return to the landscapes he knew, this time with a more critical, discerning, artistic eye. It was important to him, too, that UConn had a teaching program. "I knew I wanted to teach," he says.

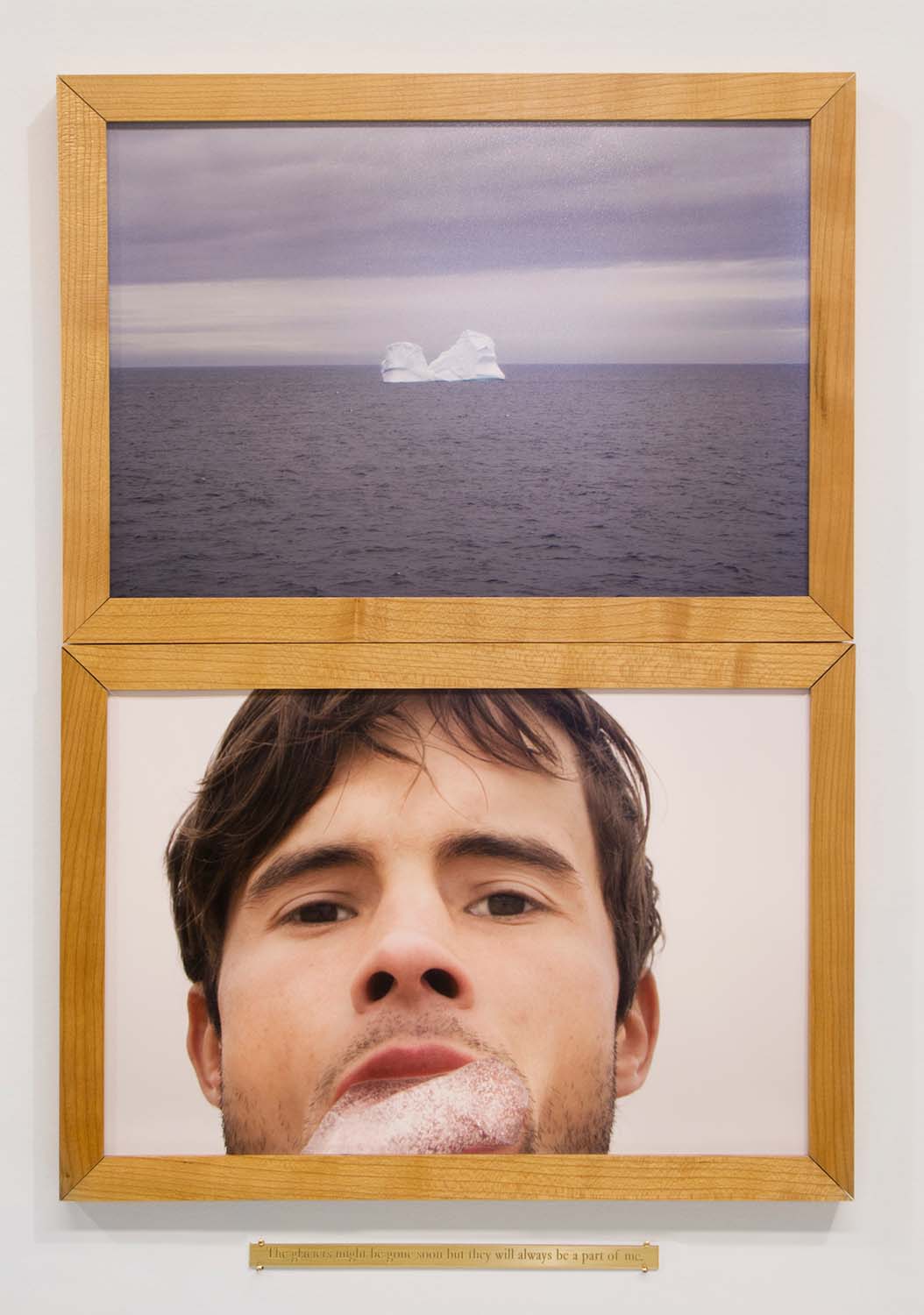

The Glaciers Might Be Gone Soon but They Will Always Be a Part of Me. For this work from 2007, exhibited in 2013, he traveled to Labrador, Canada, to see an iceberg and take a selfie eating a bit of a bergy from the shoreline.

For his first major MFA project, he decided "to walk every street in Willimantic and photograph every spruce tree," he says. "The first wave of immigrants was from northern Europe, and they brought their love of spruces here and planted them everywhere."

He liked the connection back to this history. "Spruce trees are the last living link to the industrial revolution in that town," he says. "I also love trees, and it was a way to photograph trees."

He carried a paper map and crossed off each street as he went. He wore down his walking shoes traversing neighborhoods; it turned out there were some 3,000 spruce trees in the city. He culled thousands of photos into "Every Tree in Town," a book and an exhibition at the William Benton Museum of Art and in downtown Willimantic.

"'Every Tree in Town' is a stunning and committed book. I remember the project for many reasons, but first and foremost because it was so Matt," says Janet L. Pritchard, a professor and graduate advisor in UConn's School of Fine Arts. "With this work and his companion piece, 'Hometown Stones,' I felt Matt had come into his own."

It was UConn, López-Jensen says, "that brought me to that sublime place, walking far and suddenly finding a ruined red brick building in the midst of a forest of white pine, having these beautiful experiences that I want to share, that are an extension of an art practice."

"Block after block, I was spurred on by each new instance of people caring for trees."

Finding Wonder in the Ordinary

"Wonder — that's the word Mary Birmingham, curator of the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey, says truly captures López-Jensen's work.

"It's an innocent wonder, unspoiled by the world, and it begins with unbridled curiosity," she says. "Matthew has given himself permission to be in awe of what he discovers as he walks — about nature and man's interaction with nature. Once you give yourself that permission, there's so much to see and wonder about."

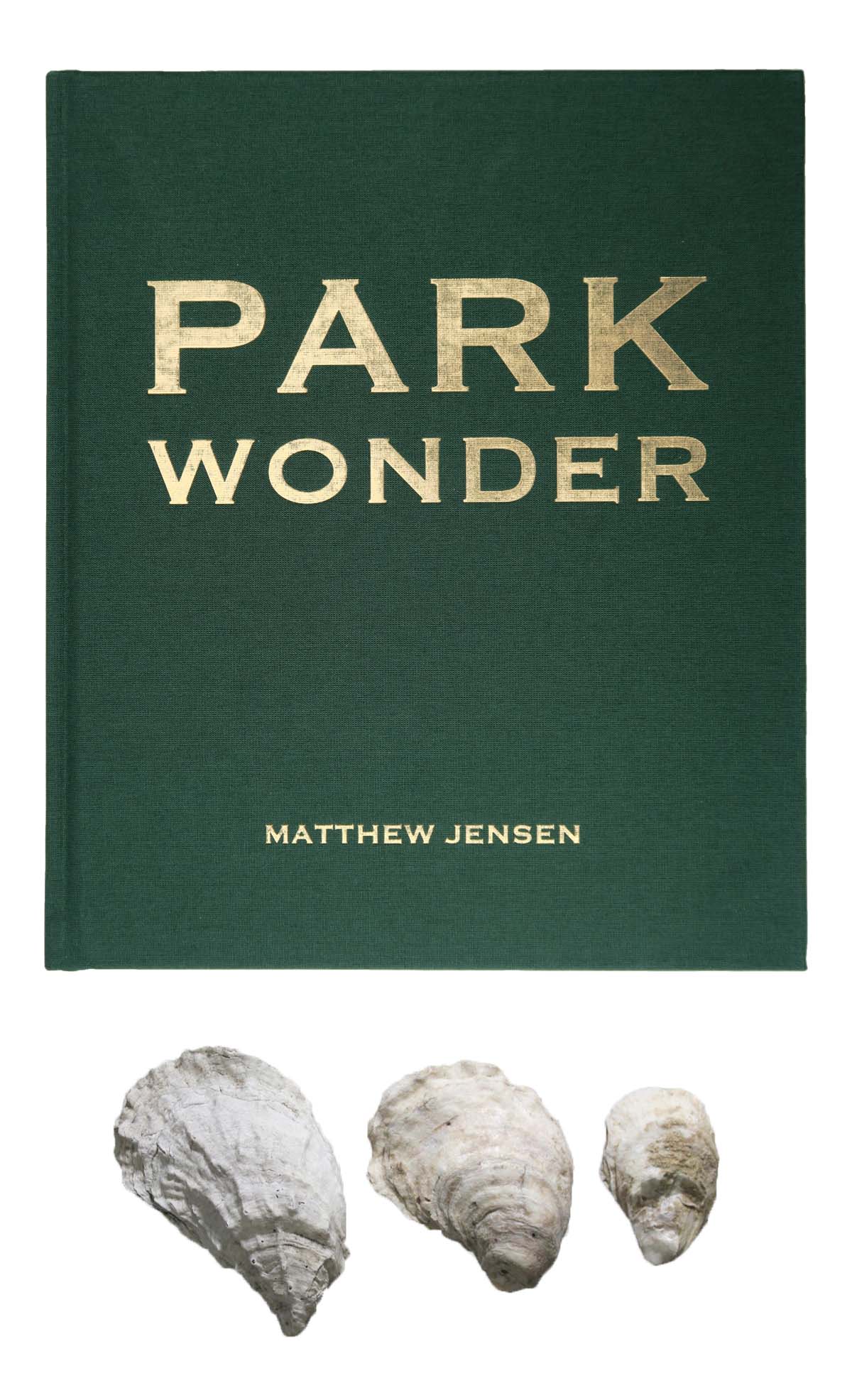

Birmingham worked closely with López-Jensen for almost two years as he developed "Park Wonder," a project exploring four historic New Jersey landscapes — the Passaic River, the Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, the Watchung Reservation, and the Gateway National Recreation Area at Sandy Hook, in a 2017 exhibit, a book, maps, and a series of public walks.

Pin Oak, Red Hook, Brooklyn.

During that time he applied for, and was awarded, a Guggenheim Fellowship in photography, "which was huge," Birmingham says. "The fellowships are so hard to get. It enabled him to go the extra mile and do exactly what he wanted to do."

Adds Pritchard, herself a Guggenheim Fellow, "A Guggenheim Fellowship is a special honor and rare opportunity, which is widely recognized and can open doors. I imagine Matt's beautiful and genre-challenging book 'Park Wonder' would not have come about otherwise. I am proud to have a copy from him in my library."

Sometimes All It Takes Is One Tree to Turn a Person into an Environmentalist

While his eyes are trained on beauty, López-Jensen can't help but notice the blight on so many species of trees as he travels along the Taconic Parkway or up into Connecticut, the effects of warming winters and climate change"“related pestilence. "It's depressing," he says.

But he's heartened by the next generation of emerging artists and environmental activists. He teaches art and photography at Parsons School of Design at The New School and at Fordham University, where he created the course "Art and Action on the Bronx River," working with the university's Center for Community Engaged Learning (CCEL) and the Bronx River Alliance.

The 49 States, a landscape series on exhibit behind Blue Lake Pass by Maya Lin for the show Surveying the Terrain at CAM Raleigh in 2014.

"Matt incorporated hands-on experiences — walking, boating, collecting, and performing ecology and clean-up activities — into a visual arts course," says Julie Gafney, executive director of the Fordham CCEL. "Another similar course might have seen students spending nearly all of their time in the studio. These hands-on experiences better acquainted students with the ways that the neighborhoods near Fordham adapt, grow, and build solutions, and provided inspiration for students' original visual art projects."

All it takes sometimes to get people to care about the environment is the chance to engage with nature up close, says López-Jensen. "By getting people more engaged through the arts in a specific landscape, I hope they become engaged in all things landscape."

López-Jensen takes action another way — as a member of Citizen Pruners, part of Trees New York, which trains volunteers in tree care, biology, identification, and pruning. He's inspired, he says, by the tender ways people tend to an urban tree in their midst. For "Tree Love: Street Trees and Stewardship in New York City," a recent photo series featured on Terrain.org, he walked hundreds of miles in neighborhoods all over the five boroughs.

"Block after block, I was spurred on by each new instance of people caring for trees," he notes. "Old growth, self-planted, stunted, scarred, broken, coppiced, blighted, blight-resistant, rare, overpruned "¦ each tree exhibits time and circumstance in its own way."

In one photo a precariously leaning small red plum tree stands in the Woodlawn section of the Bronx. Someone cared enough for this tree to cut a two-by-four to the exact size that would perfectly prop it up, marvels López-Jensen, finding hope in that "small gesture."

It's a lovely way to fashion a working life, he says — walking, creating, teaching, and forever looking.

Park Wonder, 140-page book of essays and photographs, available online at Guttenberg Arts.

Honey Locust and Scaffolding, East Village, Manhattan, 2019, from Tree Love series.

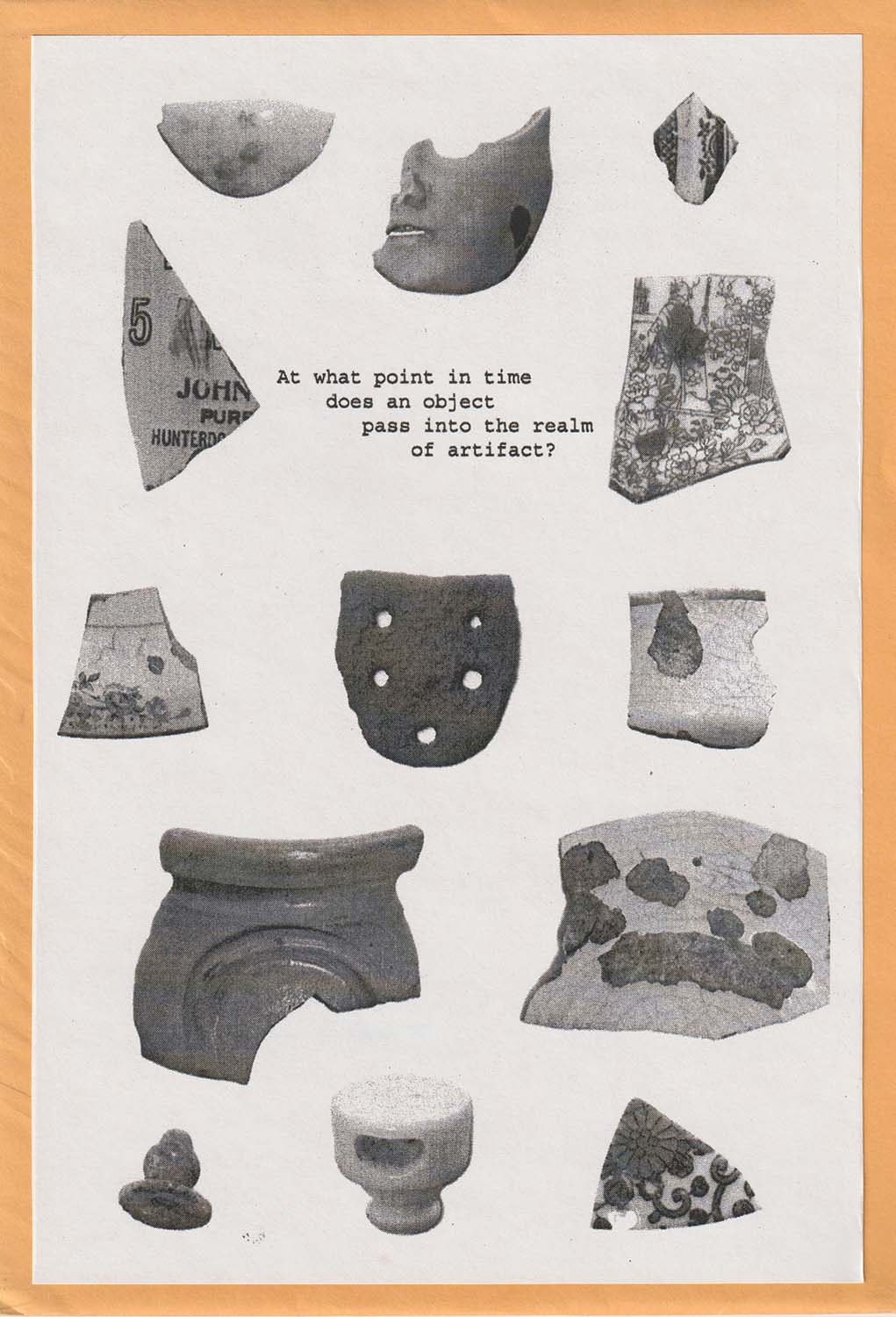

A page from Walking Inwood, 2011, an artist book featuring artifacts collected on walks in Inwood Hill Park.

I’ve been fascinated by trees for many years. So, this is very interesting.