Doctor Who?

Dexter Gabriel, aka P. Djèlí Clark, was born in Queens, New York, but his first memories are of Trinidad and Tobago, where his immigrant parents sent him to live with his grandparents at age 2.

He describes himself as a typical kid growing up in the West Indies, in “the cultural milieu of African and Caribbean music and folklore, and Hindu culture and foods.” He ate lots of roti and curry chicken, and he loved it. During Carnival season, he watched costumed and head-dressed dancers line the streets to calypso and soca music. He’d scamper around, collecting dropped sequins. “I thought they were magical,” he says.

When he returned to New York at age 7, he found a toddler girl clinging to his mother — his younger sister — and an urban Staten Island a world away from his former strong Black Caribbean community. And in contrast to his lenient grandparents, his parents were more firm with work ethic and rule following.

His mother was firm in other ways, too. The public elementary school wanted to hold Gabriel back a grade, assuming his West Indian education had been poor. “My mother marched me in to see the principal, took a book from his wall, and told me to read it.”

Gabriel, who had learned to read at age 4, read every word. The principal allowed him to enter second grade.

He also recalls his mother sitting him in front of “ABC World News Tonight” and ordering him to listen and learn. “‘People will think you are less intelligent with your accent,’ she’d tell me. She could always code switch easily back and forth, dropping in and out of her Trinidadian accent easily. But my father never did.”

Both parents cultivated a love for science fiction in their son, whose childhood was filled with “Dark Shadows,” “The Twilight Zone,” the BBC’s “Doctor Who,” and other sci-fi favorites. But his mother forbade him to watch the “Star Wars” movies — because there were no Black characters. “I think it was because of her early like of ‘Star Trek,’ with its diversity, that she had problems with ‘Star Wars’ lack of diversity. ‘What are they trying to say?’ she would huff. ‘That there are no Black people in the future?’” Still, Gabriel read all the sci-fi, fantasy, and horror books he could get his hands on at the local library. He loved immersing himself in the alternative universes and histories.

“For years now, P. Djèlí Clark has quietly been cranking out short fiction that is as fantastical as it is attuned to social justice. Through captivating characters unlike any we’ve ever seen before and sumptuous worldbuilding that twists the familiar into something exciting and new, Clark works his own magic.”— Alex Brown of Tor.com, in a 2019 review of “The Haunting of Tram Car 015”

When Gabriel was 11, the family moved to Spring Branch, Texas, so his father could seek work in a developing oil boom. Gabriel dreaded leaving New York and all his cousins there. And when they arrived in Texas, he says, the race-related problems began immediately.

A pickup truck in Gabriel’s apartment complex had a Ku Klux Klan sticker on it. People drove by their family in the daytime, shouting the n-word. Gabriel’s mother ran home at night from her job as a telephone operator at Southwestern Bell, for fear of being accosted. Students in his school made racial jokes, and the one other mixed-race student in Gabriel’s class was labeled a “problem child,” and was regularly suspended.

“There was an enduring racial animus there,” he says. “These were things I didn’t understand at the time, and I didn’t have words for it.”

As soon as his family could afford it, they moved to the southwest side of Houston, which at the time was predominantly Black and Hispanic. For high school, Gabriel’s mother got him into an arts magnet school. He remembers feeling conflicted: The local public school had lots more Black and Hispanic kids, but the magnet school had a better curriculum. He remembers a Black chemistry teacher and, while Gabriel admits to not caring much about the subject, the teacher set a powerful example. “He did not suffer fools lightly. He was there to be your teacher, not your friend. As a Black male, to run the classroom that way was fascinating to me.”

After high school, Gabriel studied political science and history at Texas State University. One of his history professors there noted his keen interest in the subject, telling him he had a knack for it, and asking if he’d considered going into academia. “It seemed like something in the sky,” scoffs Gabriel, who didn’t think anything more of it. He just couldn’t see himself as a professor. So after graduation he got a job as an IT systems analyst at a small corporation, where he spent much of his time “helping people reboot their computers.” It wasn’t long before he felt the academic world calling him back. “Turns out I liked the academic world more than I thought I did,” he says. “It shaped my understanding of life, especially my own. I was drawn to cultural anthropology, and the history of scientific racism.”

Gabriel returned to Texas State for a master’s in history. His thesis examined the last surviving ex-slave narratives from the Works Progress Administration. Although his thesis focused on violent acts by enslaved women to protect themselves from abuse, it was clear that some slaves were concealing the truth, depending on who the interviewer was. Some believed that they would be compensated if they told mostly white interviewers what they wanted to hear.

“It became necessary at times to read between the lines for cleverly disguised meanings, or to make note of the shift in tone when there was a Black interviewer,” says Gabriel. “I found them heavily informative.”

Throughout his education his love for New York never waned, so after he graduated he moved to Brooklyn and took another break from academia, accepting a “weird temp job” on Wall Street. For the next four years he worked at Standard & Poor’s, entering and analyzing data on securities. In 2007, he says, he began to notice many more mortgage-backed securities than usual. “We would get stacks of them, all with AAA ratings. I would see it every day, and people were like, ‘Wow, another AAA+ rating.’ Everyone was flying high. Then, well, the bottom fell out of housing.”

He arrived one morning and instead of the usual stack of hundreds of securities to enter, he had one. “That was the moment when I was like, ‘Okay, I’m out of here.’” Taking the stock market crash as a sign, he applied and was accepted to the Stony Brook doctoral program in history.

In line with his previous interest in the process of emancipations, he began studying the Black Atlantic: the history of the movements of people of African descent from Africa to Europe, the Caribbean, and the Americas (primarily through the transatlantic slave trade) and their many cultures and communities. For example, Britain abolished slavery by decree, and in its wake, pamphleteering both for and against this method of emancipation proliferated in the U.S. “Abolitionists said: We know this can be done. We can end slavery by decree. It’s the safe way and the right way,” says Gabriel. But the movement was thwarted, he argues, by exaggerated evidence that these steps had collapsed Britain’s Carribean economies.

His work in this arena earned him a Frederick Douglass Institute fellowship at Indiana University of Pennsylvania for his final year, which helped him to the finish line for his dissertation — a line he crossed while feverishly checking his phone for updates on his newly published fiction.

A Double Life

Gabriel’s life had been influenced at the outset by his West Indian upbringing, rich in folklore and mysticism. He later dove into those Western science fiction book and television classics. But much of his beloved sci-fi and fantasy fiction didn’t pass, or barely passed, his mother’s litmus test: It lacked Black and Latino characters, women, and LGBTQ people at the center of the stories.

Gabriel had from a young age written fiction as a hobby, loving the idea of world-building, of dystopias, of a kernel of history spinning out into a new alternative reality. And the absence of people like him in those stories colored his writing from day one.

“I felt a need for more diverse tales with more diverse characters drawn from more diverse sources,” he says.

Thus was born Phenderson (P.) Djèlí Clark.

“My sibling book club picked ‘Ring Shout,’ by P. Djèlí Clark. It’s the story of a Black woman in 1920s Georgia who discovers that the KKK is actually composed of demons. It’s paced wonderfully so it will not be over too soon.”— Stacey Abrams, author and voting rights activist

The pseudonym stems from family history: Phenderson was his grandfather, Clark was his mother’s maiden name, and Djèlí is a take on a West African word for “storyteller.”

Gabriel says that writing fiction was always his reward for completing some other “serious” task. Finished your dissertation proposal? Now finish that story and send it out to a magazine. Passed your generals exam? Make some “night coffee” and have a 2 a.m. writing session.

“All my creative writing happens when the sun is down and everyone is in bed,” he says. “I always kept them separate because I was doing the fiction writing for fun,” he adds. “I never expected to publish anything — I would send something off and forget about it.”

However, as the years progressed, and he began publishing short stories on speculative fiction websites, Gabriel realized the themes were not nearly as separate as they seemed.

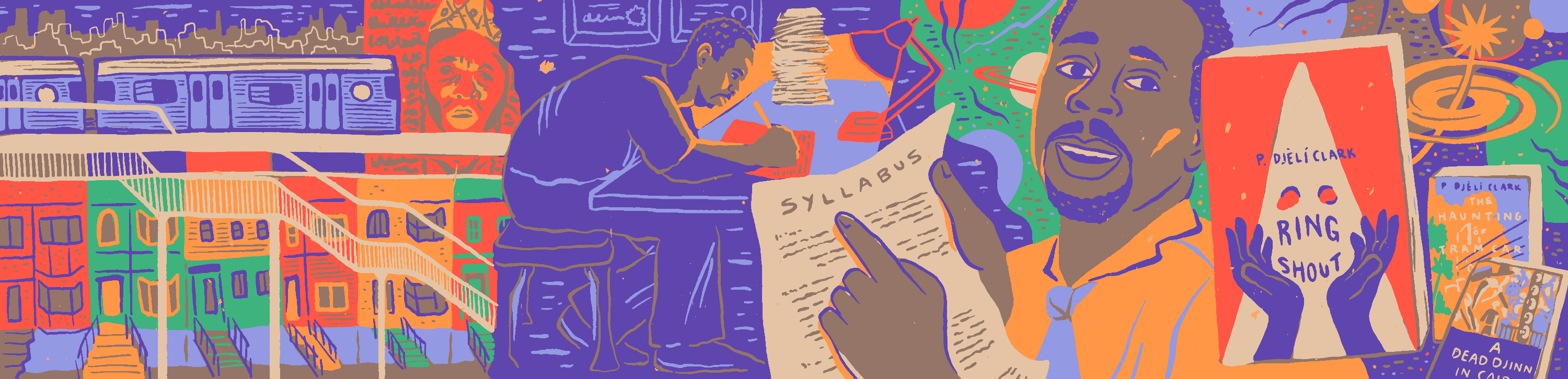

His first published short story, “The Machine,” is a 600-word tale about a contraption that “keeps the world going,” and the groups of people trying to worship, fix, or destroy it. But fast-forward to 2015 — six years of graduate school and eight published stories later — and you find him with a 10,000-word story called “A Dead Djinn in Cairo.”

By then, it had become obvious to Gabriel that his history work was influencing his speculative fiction. “I was just immersed in the things historians think about, and it came out on the other side. In history we speculate when we don’t know things. But we wouldn’t speculate there would be, for example, werewolves,” he jokes. “That’s the fun of speculative fiction.”

And so more years passed, with Dexter Gabriel working down his windy path toward an academic career, while P. Djèlí Clark came out at night to write about racist demons and supernatural disturbances. So separate were his worlds that when Gabriel landed an assistant professorship at UConn in 2016, he didn’t tell a soul about his fiction.

Since then, a few of his colleagues have uncovered his double life, with versions of the same reaction: “Why didn’t you tell me you’re a fiction writer? That’s so cool!”

The answer is complicated, he says, and wrapped up in academic, class, and race issues. “I’m a first-generation college student, and I took it all the way to a Ph.D., so I really don’t have a role model to look to,” says Gabriel. “My issues of identity, of being a Black man, an immigrant, and a first-generation college student, all weighed in consideration of how I should present myself.”

Academia has not always been kind to people who publish nonacademic writing, let alone people of color who do so, he says with frankness. So he used a pen name, and proceeded with caution. He says he knows professors at other universities who write fiction, but may never go public with their pen name. And to top it off, he says, being in academia and being a man of color are both obstacles in the sci-fi writing world.

He might even have kept things relatively under wraps for many more years — at least until he achieved tenure — if not for the great success of his most recent novella, “Ring Shout.”

In the story, Maryse, a monster hunter in a dystopian Macon, Georgia, leads her band of resistance fighters through a world where white supremacists conjure demons from the Earth, called Ku Kluxes, to spread fear, violence, and hate. The book takes its name from rituals performed by African slaves, in which worshipers move together in a circle, stomping, shuffling, and clapping.

The novella was a finalist for the 2021 Hugo prize, received national Nebula, Locus, and Alex awards for 2020, and was a finalist for more than seven other national and international awards, making it one of the most decorated new works of speculative fiction this year.

It was a New York Times Editor’s Choice book, was reviewed by NPR and Publisher’s Weekly, and was recommended by Stacey Abrams, whose book club read it in May. And it’s currently in development as a television series with producer Skydance Media, known for its production on “Star Trek,” “Terminator,” and “Mission: Impossible” films. “Technically I’m an executive producer, but I don’t really know what that means,” says Gabriel with a laugh.

Gabriel loves hearing interpretations of his fiction, even those that reach beyond his intended connections to history. Some readers have likened scenes from “Ring Shout” to the Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol. It’s made for good discussions in his classes this year, especially in his “Slavery in Film” class. “I like to hear how people make connections between my stories and the real world,” says Gabriel, who also teaches “Comparative Slavery in the Americas” and “Making the Black Atlantic,” both courses he created when he arrived at UConn. He’s also taught a graduate course on the Black Atlantic, and a senior seminar on historical craft and writing.

Next Up

Gabriel — or should we say Clark? — has come full circle with a full-length novel that takes place in the universe of his first big story. “A Master of Djinn” came out in May, with themes of colonialism and the history of the Egyptian city, along with mystery, fantasy, and romance.

Gabriel hasn’t used his fiction in class (although some colleagues have used “A Dead Djinn In Cairo” in their courses), yet somehow, he says, his students figure out that he writes fiction. And he’s become OK with that — geek culture is popular now, he says, and anything that helps him look cooler to his students can only be a good thing.

Doubling up as ever, Gabriel also has an academic book in its final stages and planned for publication later this year, “Jubilee’s Experiment: The British West Indies and American Abolitionism.” After that comes out, he’ll of course deserve a reward — perhaps another Djinn book, written in the wee hours?

“It’s been an unorthodox ride,” says Gabriel/Clark.

“But a good ride, a very good ride.”

I majored in history and economics in Kansas City, Mo. and have read a lot of history and thought White have become a specialist in black history. I grew up on an 80 acres farm north of Oskaloosa, Iowa but my family moved to Fayette, Mo. in 1956 when I was a freshman in high school. They school were integrated in 1955 but Jim Crow was everywhere in town. I encounter Jim.Crow and I had no real information of how complete it was . My mother graduated from high school in 1926 Oskaloosa and blacks were in her high Year book. Only one black family were in my brick two story school in small community of Lacey three girls older than me but top students. I did labor history for 25 years and read what books on blacks history that I could find including American history but many books I could find until I discovered Thrift books then old books were cheap. So I have a house full of books but started out as a chemistry major but got a chance from a neighbor son in Labor Relations at a General Motors Assembly Plany in Kansas City a guaranteed job so my older brother and I accepted after just one year of college. So I finished by going 6-9 hours a semester and summer classes. Company reinmersed me. Came across 15 books recommended by you that was in the Washington Post. First I had heard of you so looked you up and read about your fiction writing plus your books on history which I will buy and read. Worked 44 years and retired in 2006! Will be 81 on July 8, 2023! Thanks and congratulations for what you have achieved. -Wlllard BolingerbKansas City, Mo.