The Instructor:

Despite her decades in the classroom, Doreen Simons never planned to be a teacher. She wanted to be a social worker, so studied sociology at Gaulladet University in Washington, D.C., a private university for the education of deaf and hard-of-hearing people. But while she was a student there a professor noticed how well she used American Sign Language (ASL) and asked her if she would teach it to hearing students at an area high school.

Simons was, at the time, relatively unusual — a native speaker of ASL. Unlike most deaf children, 90% of whom are born to hearing parents, Simons was born deaf to deaf parents, both of whom signed. So she learned the language from infancy just as a hearing child would acquire English. This was also before ASL had become the predominant language of American deaf people.

Simons gave teaching a try and liked it well enough that she taught on the side while pursuing degrees in deaf education and deaf rehabilitation. That brought her to UConn, where Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor of Linguistics Diane Lillo-Martin, who researches how ASL is acquired, recruited her for a study. Simons was shocked to learn that, despite the research into ASL, there were no classes in the language at UConn.

"If you are going to have graduate students researching it then they should know it," she says. "I volunteered to start teaching."

Simons taught UConn's first ASL course in 1986, when very few American universities offered classes in the language. She eventually finished her master's in deaf rehabilitation and a certificate in deaf education at New York University but kept teaching at UConn as demand for the courses grew, joining the faculty full time in 2002.

Now there are nine sections of the Intro to ASL course each fall, which readily fill up, as well as a long list of other courses, including classes on deaf artists, deaf women's studies, and ASL literature, which Simons also teaches. Moreover, as of this fall students can earn a bachelor's degree in ASL Studies at UConn, making it just one of a half dozen or so schools in the country to offer that — and the only one in Connecticut.

The Class:

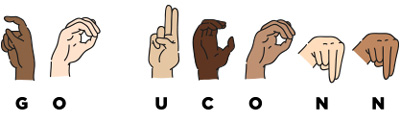

Simons uses a full-immersion approach in Intro to ASL class, starting from the very first day when she invokes her one rule — no talking, ever. The class is taught in silence. Students can only communicate by signing.

"They have to turn their voices off," she says. "Sometimes I see them trying to mouth certain words. That's them holding on to the English, and they need to focus on ASL."

ASL is truly a foreign language for English speakers. It has its own grammar and syntax, which is completely different from English. Some signs do not even translate into English, says Simons. That is why students need to approach it like any other language they are learning.

They also have to let go of listening, she says. ASL is a visual language that they have to watch. Simons also teaches them to use their facial expressions and body language, which are key elements of ASL. Without them, the language loses much of its meaning, she says. Even how your hand is oriented, whether your palm faces someone or not, can change the meaning of a sign, she says.

"Some people will have the signs on their hands but it doesn't match what they are trying to say because it's not on their body," she says.

Teaching Style:

When asked to describe herself as a teacher, Simons says, "Pushy." She has her students stand up when they sign. She stops them when they whisper to each other. She points out when a signing student is not using their facial expressions, which she equates to a speaking person using a monotone voice. She pushes the students, she says, because it is the only way they will ever learn the language.

"Students get frustrated, and I'll ask how often they practice. If it's an hour or two a week that's just kind of a joke, honestly. You have to work at those skills."

She also describes herself as blunt, which she says is typical of deaf culture. When hearing people might equivocate, deaf people get straight to the point, she says. If you've gained weight or gone bald, a deaf person is likely to say so, she explains. That is part of deaf culture, which she also teaches about in the class, so students understand better the world the language comes from.

Why We Want to Take It Ourselves:

ASL is now the third most studied language in the U.S., behind Spanish and French, says a 2016 study by the Modern Language Association. Its popularity speaks to the long list of reasons anyone might study it. Some students plan to use it professionally in fields such as interpreting, education, social work, and speech pathology. Simons finds that students often have a family member or friend who is deaf. To communicate well with our deaf community members we need to learn a new language, a challenging thing for an adult. We need a teacher who's pushy and blunt to help us get it done and get it done right.

By AMY SUTHERLAND

Photo by Peter Morenus

I have a teen very interested in learning ASL. Sadly our local school insists we pay $600 for the class even though it is a hardship and the teen has a hearing loss. She was unable to take the course. Perhaps next year, for she does aspire to attend UConn and work with children with hearing and speech difficulties like herself.