CSI Boston

The Boston Police did not have quite enough evidence to charge a suspect in a horrific 2013 murder of a young woman. They turned to one of the department's forensic scientists — Joe Ross '04 (CLAS).

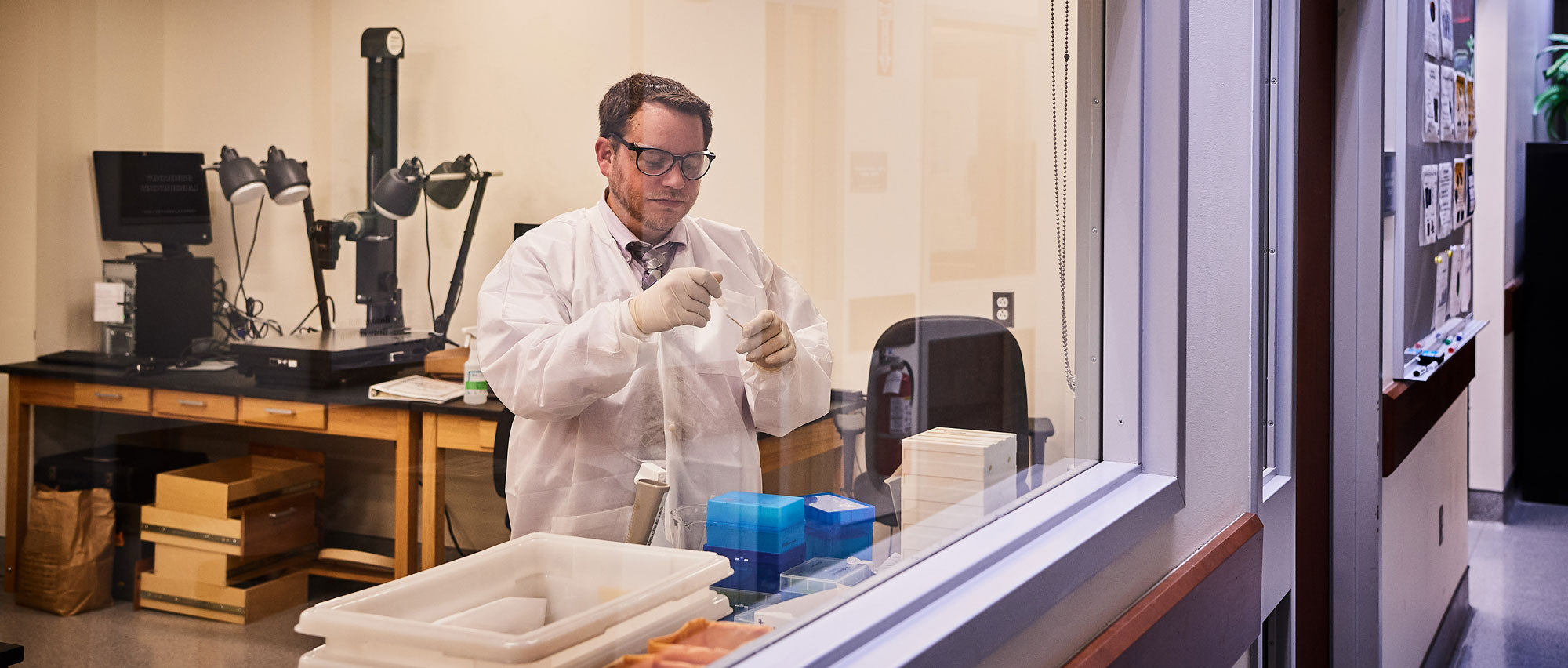

Photo by Peter Morenus

CSI Boston

The Boston Police did not have quite enough evidence to charge a suspect in a horrific 2013 murder of a young woman. They turned to one of the department's forensic scientists — Joe Ross '04 (CLAS).

Photo by Peter Morenus

When you ask Joe Ross '04 (CLAS) what the popular TV show "CSI" got right about the jobs of investigative forensic scientists he looks at the ceiling and thinks for a few beats. "Hmmm," says Ross, a forensic scientist now in his 10th year as a member of the Boston Police Department. "They get a lot wrong. They think everything gets done in a day. It can take us a month."

They don't carry guns or drive Humvees, and you can't get DNA from absolutely everything, he adds. He knocks on the table between us. "This wouldn't work for example." You can't get it off something someone only touched. The DNA he looks for is found in body fluids. Finally, as if he's fallen on a small shred of evidence at a crime scene he exclaims, "The science. They get the science right."

The science happens to be Ross's favorite part of his job, the part that not even the TV series manages to make look all that sexy. But Ross loves nothing better than to work in his lab, listening to early aughts hip-hop on the radio as he searches for microscopic bits of DNA.

"I'm a science nerd," he says. "I like knowing what's going on at a molecular level."

Knowing what goes on at the molecular level is how Ross helps the Boston Police solve crimes. He most often works on sexual assaults, and breaking-and-entering cases, but also homicides. Last year Ross worked on 28 of those, including the horrific double murder of a couple in a South Boston luxury condo. Four or five times a year, Ross is on-call to go to crime scenes, and that happened to be his week. He and a fellow scientist were some of the first people to arrive. There was so much blood it took them 18 hours to collect all the evidence.

"Crime scenes certainly stick with you, especially the ones where the bodies are still there. I could picture all the victims I've seen in my head. But you know you are working. You get on with your job."

Sports In His DNA

Though Ross, 36, jokes that everything about his job is "morbid" you'd never know that by his upbeat manner and certainly not by his desk, what with the Star Wars bobbleheads and raft of photos of him, wife and two young sons at sports game after sports game. Ross has tacked up the season schedules for the Red Sox, Bruin and Celtics. Above those our three childlike paintings that Ross made in an art class held in a bar, where you paint with one hand and drink a beer with the other. One is, of course, of Fenway Park, with little red dots for the fans. Ross laughs as he scans his artwork. "I'm getting better."

Ross was an avid sports fan growing up in Guilford, Connecticut, but nothing on the scale like he became at UConn, where he was obsessed with all things Huskies. He was a fixture in the stands with his face lacquered blue and white. For hockey games, he also pulled on a hat that made him look like he had a bone sticking through his head. He became known as the bonehead hat guy.

When bonehead hat guy wasn't cheering in the stadium, he was in the lab studying cellular and molecular biology. He had visions of becoming a research scientist, toiling away on new drugs for biotechs. Then in his senior year he signed up for a criminology class taught by two adjunct professors, both working forensic scientists at Connecticut State Crime Lab. He found their enthusiasm for their work inspiring. When Dr. Henry Lee, a top forensic scientist in the country who has worked on a long list of famous cases including OJ Simpson's, spoke to the class Ross revamped his career plans. With his UConn diploma in hand, Ross went to Lee's graduate program at the University of New Haven.

Ross was lucky he decided to become a forensic scientist when he did. Not long after people inspired by the CSI and it's ilk flooded the field, making it nearly impossible to find a job. At 36, Ross says he is of the last generation who had relatively no trouble starting their careers. Still it took him more than six months to find his first job, working with the Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in New York City, which provides genetic testing for the police. There he was one of 200 scientists and worked exclusively in the lab. That changed when he joined the Boston Police Department in 2009. There he is one of five scientists and works directly with detectives, including on some of Ross's favorite cases -- cold cases.

In 1980 a man had been killed in his apartment, and though police had a suspect, they did not have enough evidence to charge him. They had pieces of his clothing but those could only be examined for fingerprints then and nothing consequential was found. By 2012 it was possible to swab clothing, what is called "wearer" samples, for DNA. Ross began testing the items. He didn't find DNA on anything except a shirt. It belonged to the suspect. Finally, the police could charge him.

"Solving one that hasn't been solved for almost 50 years is incredibly satisfying," Ross says.

Since Ross became a forensic scientist DNA testing has become increasingly sensitive so that genetic material can be found where it once couldn't. In 2013, a man abducted a young woman, drove her to ATMS around the Boston where he forced her to withdraw money, and then stabbed and strangled her to death. Ross processed the suspect's shoes, which appeared to have been wiped clean. Still the scientist found about 30 droplets of blood, each about the size of a pinhead. In those he found the victim's DNA. With that key evidence, the police were arrested the suspect.

"Research scientist do research their entire lives and can have nothing ever happen," Ross says. "I feel like I make a difference on a daily basis."

—amy sutherland