By a Thread

Cambodian refugees, severely tortured 40 years ago, are suffering from trauma-related diseases today. A team of UConn professors is helping them here and in their homeland.

By Julie (Stagis) Bartucca '10 (BUS, CLAS)

Illustrations by Michelle Kondrich

After years of civil war, Pol Pot's Khmer Rouge regime invaded the Cambodian capital city on April 17, 1975. Dressed in black uniforms, the communist soldiers forced two million Phnom Penh residents from their homes, saying they were being evacuated briefly to avoid American bombings. Instead, they walked in droves for days. Some recall being separated from family members; others remember being tied together by sewing thread and warned that if the thread broke they would be shot.

The evacuation was, of course, not about protecting the Cambodians but about serving the Khmer Rouge mission to create collectivized farms. Those Cambodians who survived the journey were brought to work camps in the countryside and tortured and starved for more than three years.

Lila Plawecki was 10.

The tears flow easily as Plawecki, now 53, describes the abuse she and her parents endured. Her father, once a dignified soldier, was yoked like a cow, forced to pull carts through the fields.

"After that, I never see him," Plawecki says. "They kill him."

They walked in droves for days ... tied together by sewing thread and warned that if the thread broke they would be shot.

They walked in droves for days ... tied together by sewing thread and warned that if the thread broke they would be shot.

"The genocide continues," says Thomas Buckley, UConn associate clinical professor of pharmacy. "It manifests itself now as chronic disease."

In a regime focused on agricultural revolution, those from the city, "new people" such as Plawecki's mother, were tortured particularly harshly and in many ways, including through starvation. While reaching into a hole in the ground, trying to catch crabs for her family to eat, Plawecki's mother was bitten by a venomous snake. She died two days later.

The orphaned Lila was taken to a work camp for children and forced to labor in the fields from sunup to sundown with hardly anything to eat. The Khmer Rouge berated her, telling her she wasn't working hard enough. They rapped her fingers with bamboo, breaking her hands and permanently damaging her nerves.

Still not a teenager, Lila was jailed and raped and starved. The Khmer Rouge ate in front of their prisoners, giving them nothing. Lila and the others stole any food they could find — even if that meant bugs or putrid, rotting rice — and hid it to eat when the soldiers were gone. Sent to get meat from dead cows or elephants for the Khmer Rouge to eat, they would gnaw on the tough skin.

Though Lila Plawecki survived the reign of Pol Pot, which ended in January 1979, her anguish endured. Sponsored by her sister, she came to the U.S. in 1990.

And then, for 26 years, she suffered in silence.

After the Trauma

An estimated two million people died during the Cambodian genocide. But millions like Plawecki survived the trauma. All these years on, they still suffer.

"The genocide continues," says Thomas Buckley, UConn associate clinical professor of pharmacy practice. "It manifests itself now as chronic disease."

The prevalence of depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the Cambodian-American immigrant/refugee population is more than 10 times the national average, and they experience hypertension, heart disease, diabetes, stroke, and death from diabetic complications at a rate six times that of the general population.

"When you have such astronomically high rates, it shows this population has been ignored. They have low BMI [body mass index], yet they're dying of strokes and cardiovascular disease. It's so unexpected," says Buckley. "Khmer Health Advocates considers this a manifestation of genocide because the American health care system has not addressed the ramifications of genocide. Who would've thought you'd get diabetes from a high level of cortisol that happened over 40 years ago?"

Buckley, along with S. Megan Berthold, School of Social Work associate professor, and Julie Wagner, UConn Health professor of oral health and diagnostic sciences, have dedicated their work to battling this phenomenon, not only in Cambodians but in other refugee populations.

The three faculty members, all principal investigators at UConn's Institute for Collaboration on Health, Intervention, and Policy, have worked with West Hartford, Connecticut"“based Khmer Health Advocates (KHA) since 2006, developing programs that improve health care for Cambodian refugees in Connecticut and Massachusetts. KHA is the only Cambodian-American health organization in the U.S.

"Sister"

For more than two decades, Plawecki worked on engine pistons at a machine shop. The detailed work required manual dexterity, but the incessant pain in her once-broken fingers made the task difficult. Suffering on the job and severely depressed, she nonetheless worked 14-hour days.

In October 2016 she suffered a bad fall at work. "After that, I just wanted suicide because I couldn't work for a living, no income," says Plawecki.

But while she was in the hospital, a friend told her about Khmer Health Advocates and the woman Plawecki affectionately calls "Bong Vy" — Theanvy Kuoch, also known as "Vy" (pronounced "vee"). The founder and head of KHA, Kuoch is also a survivor. Bong means "sister" in Khmer, the Cambodian language.

"My friend said Khmer Health can help. That's why I came straight to Bong," says Plawecki, who lives in Burlington, Connecticut. "I don't have appointment, I don't know what Bong Vy look like. I just came straight here, and now I have another life."

In her new life, Plawecki is comfortable talking about her past. Though sometimes she struggles to find the words in her second language, she just needs a minute to think through what she wants to say. Speaking in an office at KHA, Plawecki sometimes turns to Kuoch to say certain things in Khmer first. Then she either lets Kuoch translate or she takes Kuoch's encouragement and says it herself, this time in English.

It's a complete turnaround from the person she was less than two years ago: withdrawn, depressed, and scared to talk, says Kuoch. Now, "If she wants to cry, she cries; if she wants to laugh, she laughs. She's not afraid. And she's very brave."

Eat, Walk, Sleep ... is being widely implemented by UConn researchers, whose studies have proven it is particularly effective for traumatized patients with diabetes or pre-diabetes.

Eat, Walk, Sleep

When she arrived at KHA, Plawecki was not on any medication. Her doctors had never asked her about her history, and like many Cambodians, she didn't share it. Berthold, Buckley, and Wagner have developed programs to educate doctors on caring for survivors. For a long time physicians would look at refugees' symptoms separately, not understanding that PTSD and the related cortisol spikes were causing many of their patients' chronic physical ailments, Buckley says. The researchers have taught many to ask the right questions.

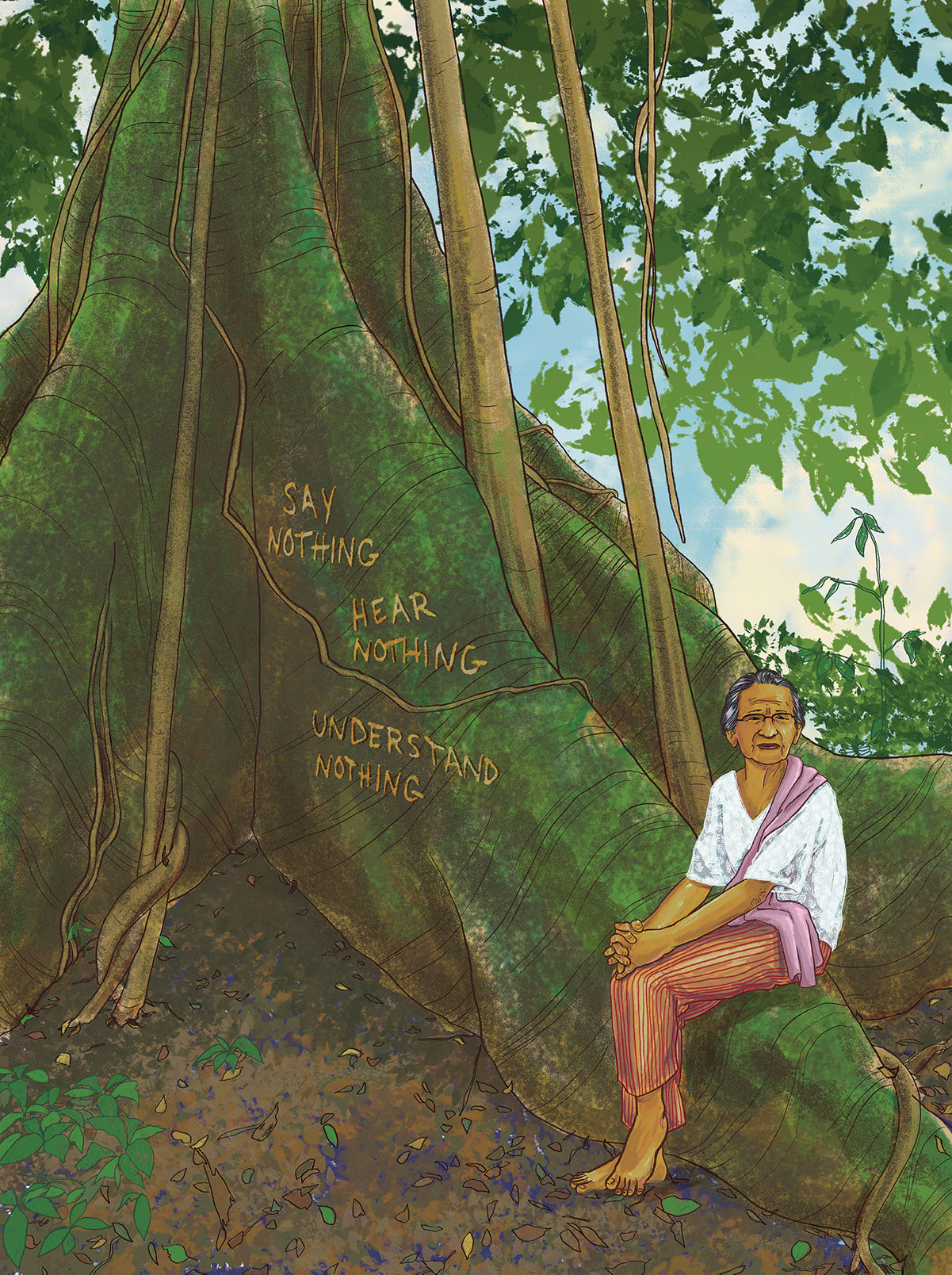

"There's a tree in Cambodia called the kapok tree. When the wind blows, the leaves remain silent," Buckley says. "The Cambodians were taught to be like the kapok tree and to remain mute to survive the Khmer Rouge.

"Physicians have a hard time breaking through," he says. "The refugees won't talk to health care providers about their trauma — and U.S. health care providers don't ask."

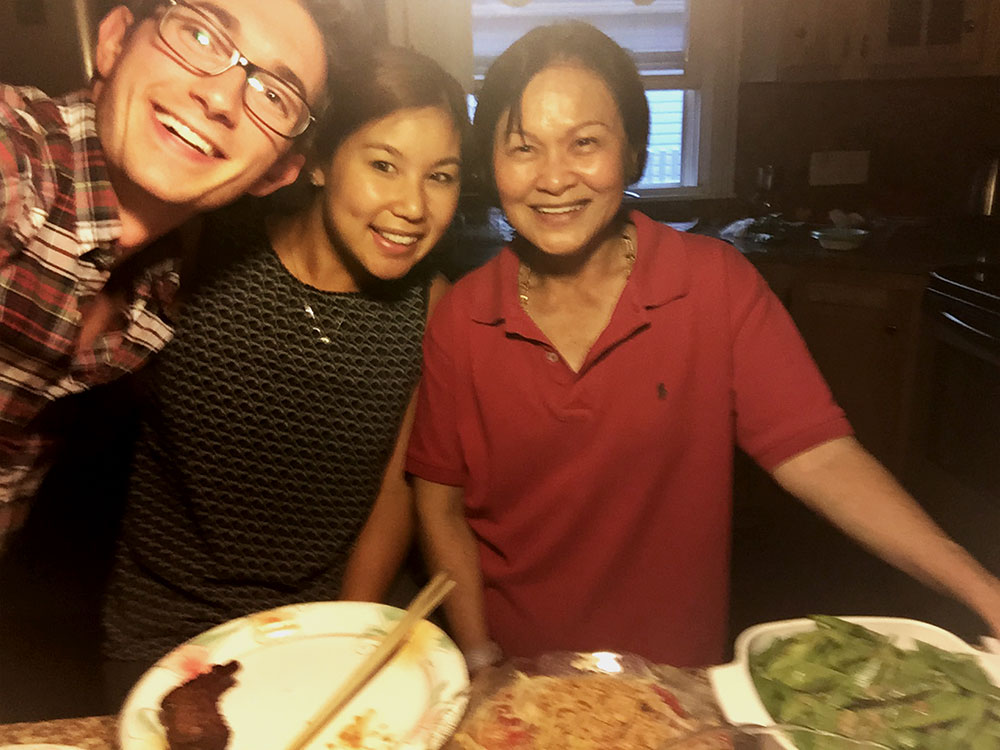

Plawecki now visits doctors with graduate students Connor Walker and Celeste Cheung (both '18 Pharm.D.) in tow to make sure all her questions get answered. Between that and the intervention from Buckley and others at KHA, she is now treated for her PTSD, depression, pain, and hypertension, and is learning the Eat, Walk, Sleep curriculum prescribed to prevent diabetes.

Initially developed by KHA, "Eat, Walk, Sleep" is a culturally specific framework promoting evidence-based dietary and nutrition guidelines, exercise routines, and sleep hygiene practices. The program is being widely implemented by UConn researchers, whose studies have proven it is particularly effective for traumatized patients with diabetes or pre-diabetes.

Through the 18-month program, Plawecki has picked up several healthy habits, like eating many more vegetables and brown rice instead of white. She walks 30 to 40 minutes every day, and has learned to meditate and not to watch TV before bed. "It helps a lot, relax my mind and I don't have bad dreams," she says.

But perhaps the most important piece of "Eat, Walk, Sleep" — and all the support offered through KHA — is the social component. The curriculum is delivered in group sessions, designed to combat the social isolation that studies have shown can be a stronger predictor of death than clinical risk factors like heart disease.

Plawecki views the people at KHA as family. The students who visit the doctor with her also took her on a 20-mile bike ride along the Farmington Canal Heritage Trail and occasionally attend her Buddhist temple in Bristol. They call her their "Cambodian mom," and gave her a ticket for their pharmacy school graduation.

In two hours, she expresses her gratitude for all of them by name — Bong Vy, Mr. Tom, Mary [Scully, clinical director of KHA], Dr. Miller, Connor, Celeste — no fewer than seven times. She says she prays for them every night.

"Broken Courage"

Over the past 12 years, the UConn researchers and their partners at KHA have discovered many ways to break through the particular roadblocks to treating these refugees. In addition to their fear of speaking about their problems, Cambodians suffer a specific iteration of PTSD, named baksbat or "broken courage," by Cambodian psychiatrist Dr. Sotheara Chhim.

Those who survived the genocide experience symptoms including fear of fear, wishing that the trauma would go away, remaining mute, an inability to speak about their fears, and loss of a sense of togetherness, according to Chhim's published research.

The population-specific symptoms and other cultural factors means "having ethnically specific community health workers has been critical to getting people to understand and accept treatment," Buckley says.

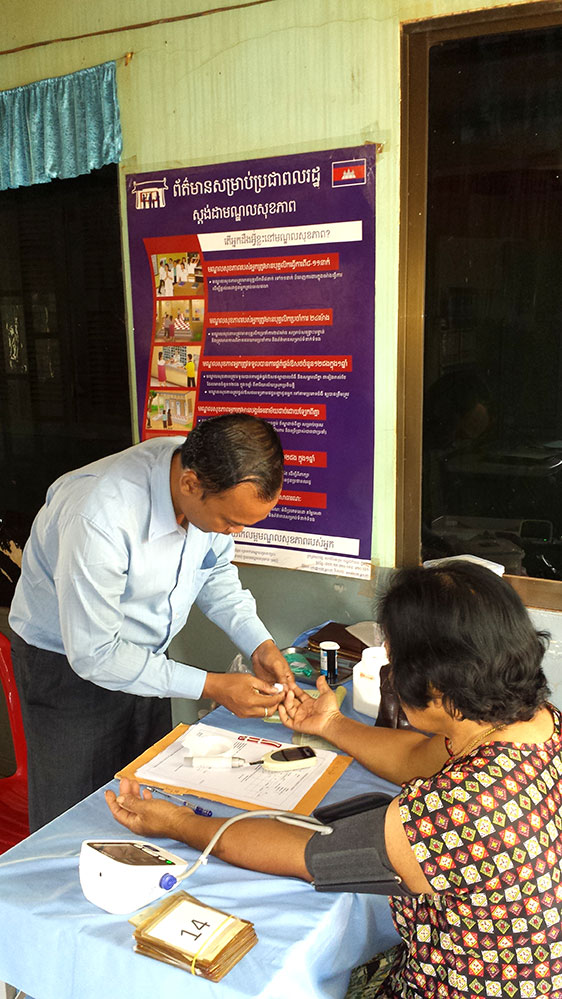

The researchers' latest collaboration, funded by a UConn Health Research Excellence Program Convergence Grant and called PLUS CamboDIA — Remote Peer Learning for U.S.-Cambodia Community Health Workers Managing Diabetes — brought Buckley to Cambodia on sabbatical. He spent this January through March in Cambodia's second-largest city, Siem Reap, setting up a program with the Cambodian Diabetes Association and KHA.

Having laid the groundwork, Buckley will oversee U.S.-based community health workers as they deliver a curriculum on "Eat, Walk, Sleep" to workers in Cambodian villages via videoconferencing this summer. The six village health workers on the ground will work with 60 new patients in remote villages who were not previously engaged in treatment and will be tracking their outcomes into next year.

"There's a tree in Cambodia called the kapok tree. When the wind blows, the leaves remain silent. The Cambodians were taught to be like the kapok tree and to remain mute to survive the Khmer Rouge."

The goal of PLUS CamboDIA is not only to reach patients on the ground in Cambodia but also to leverage the expertise of health aides in both places to improve treatment in the future.

Additionally, Buckley has long emphasized medication management in his work with refugees, and he also studied medication adherence during his time in Cambodia this spring. When he first connected with KHA, they had realized patients were not following their prescribed medication regimens.

"People were getting over-the-counter things, going to emergency rooms [to treat chronic diseases]; they were all screwed up," Buckley says. KHA hadn't realized a pharmacist could play such a large role in their efforts.

Today, though KHA has implemented programs to deal with these problems in Cambodian-Americans, similar issues persist back in the home country.

"Cambodians have a misconception that diabetes is a short-term disease. They'll take medicine for a week, like an antibiotic," he says. "We're trying to promote treatment adherence overall."

Many patients live with symptoms for many years before seeking treatment, and once they do, more hurdles prevent them from being properly treated. According to Buckley, optimal medications are often too expensive for the poverty-stricken locals, so cheaper, less effective treatments are used. Lack of knowledge and proper education about their conditions furthers the problem.

One patient Buckley met in Cambodia this year was a 52-year-old man from a remote village who has diabetes, hypertension, pain and gastrointestinal issues, and a long history of PTSD and depression.

The man's only access to medication is when the Cambodian Diabetes Association's mobile clinic visits his village, which might occur only once every few months. It's impossible to provide patients in the villages enough medicine in one visit to cover them until the next, Buckley says. And this man, like other patients of his in Camboda, is generous with his medication — too generous in fact.

He continually sacrifices the treatment that could save him to help others in his family and village, many of whom may have similar symptoms to his, but probably shouldn't be taking the same medicines.

"It's difficult to see him deteriorate," Buckley wrote in an email from Cambodia in March. "This was obviously true for the CDC clinic MD who was with me on these village visits, as he was uncharacteristically sensitive and emotional about this man, obviously upset that we can't help him more."

The doctor was struggling to maintain the stoicism typically required to administer healing concepts of his Buddhist faith "knowing he was sending the patient back into an environment filled with the social determinants of health that we can't control, and therefore the vicious cycle of health care will continue," Buckley wrote.

This vicious cycle is exactly what Buckley and his partners are trying to prevent, in as many populations as possible.

"They are angels"

What about those currently experiencing trauma-induced cortisol spikes, like Syrians coming to the U.S. today? "In 20 years, will they have the same issues?" Buckley asks.

He believes they will — unless the U.S. government makes changes to help these populations when they get here. Effecting that change is the team's goal.

While their initiatives directly help Cambodian refugees, the solutions Berthold, Buckley, and Wagner have found can be used to prevent the same chronic health problems from affecting other refugee communities.

"We want to look at how what we've learned can be applied to other traumatized refugee communities that come to the United States. We know the Cambodian community is a model of what happens to a traumatized community long term," Buckley says.

"Can we prevent some of these debilitating conditions in other groups? Can lay workers in the home country and in the diaspora leverage each other's efforts to address diabetes? That's what we really want to see."

At least for now, for Plawecki, their work is paying off.

"We've seen dramatic improvements in her pain and sleep issues, a reduction in medicine, and the social isolation piece is huge," Buckley says.

"Everyone supports me," says Pla-wecki. "I feel more strong; I'm so happy for living every single day I get up. I'm so happy.

"They are angels. If I don't meet this group, I probably suicide. It's true."

Leave a Reply