Bitcoin Believers

If you can understand pizza and poker, you can understand bitcoin — and David Noble believes you should

By Peter Nelson

Illustrations by Andrew Colin Beck

On May 22, 2010, Floridian Laszlo Hanyecz ordered two pizzas from Domino's. It's not the kind of thing that usually makes the history books. Yet his name goes on a list that includes Max Pruss, the captain of the Hindenburg, and Fred Kaps, the magician who followed The Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show — unfortunate men who will forever be remembered for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Laszlo Hanyecz's mistake was to buy the pizzas with bitcoins, 10,000 of them, a value of about $41, the first recorded bitcoin purchase. Had he held on to his bitcoins for a few more years, he could have sold them for $100,000,000. Or bought 6,253,909 large pepperoni pizzas.

It is stories like this that suggest bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies may have once been silly, but now they matter.

"The first time I taught the subject was 2016," says David Noble, from his office in the UConn School of Business. "We said, hey, here's this thing going on, and if we start collecting data on it, we're gonna know more than anybody. Because there's nobody in our position, in business schools, management, venture capitalists . . . It just wasn't on their radar screen. It was wide open. I started by just asking around, saying, 'Hey — do you know about this?'"

In addition to teaching business and management courses, Noble is head of UConn's new Peter J. Werth Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation. The 40-year-old Woonsocket, Rhode Island, native's boyishness is accented by the red Chuck Taylors he wears during our interview.

If great minds are reflected by untidy offices and desks, his mind is clearly great. There's an empty dog crate on the floor beneath the window. On a table, an easel and a painting he's begun, tubes of paint all around.

"You want to be able to explain it to people," says Noble. "Even my colleagues don't really know what all this stuff means. A lot of people still say, 'What are you talking about?'"

Think of it (to oversimplify) this way: suppose seven poker players each buy 100 chips, worth ten cents apiece, $70 total, and they start to play poker, moving chips in and out of play — making transactions. But now suppose you can have more than seven players at the table. An eighth player wants to buy in but offers to pay 20 cents a chip. A ninth player offers to pay 50 cents a chip, and so on. The value of the chips goes up, according to how much people will pay, believing they will be worth even more in the future.

Now imagine you have a million players instead of nine, making wagers, winning and losing chips, all day long, and new players are added every day. Each chip is a bitcoin.

Now take away the physical chips. Instead of shoving a stack of chips into the pot, someone says, "Hey Siri — keep track of this — I bet five chips." At the end of the game, Siri knows who owes what to whom . . . except there is no end of the game.

Then suppose instead of Siri, you have software that's infallible and doesn't think you said "five ships."

The system keeps perfect track of what everyone in the network of players owes everybody else, what everybody pays when they buy chips or gets paid when they sell them to each other or cash them in. That's called a blockchain, describing a secure ledger that records and verifies every data block or transaction and makes sure nobody tries to buy or sell the same chip twice.

Participants who run the blockchain software, called mining, earn extra chips, which are added to the collective pot at a controlled rate until a finite number is reached. The agreed-upon ledger is distributed on thousands of computers across the network, creating redundant backup and scale.

Now take away the cards, the table, the chairs, the building, the town, the state, and the country, and imagine instead a million people (or a billion) making transactions on their computers. You now have a viable virtual monetary system that exists only in cyberspace.

"There's no physical coin," Noble says. "People have a very hard time understanding that. I was talking at a high-level insurance conference, where I had to explain that you don't put it in your wallet. The wallet is more like a key, a code, and the currency is stored there. The ledger exists in the computers of the people who run the mining software. The number of miners, and the power of those miners collectively, has a lot to do with the safety of the network and the currency."

The [Man?] Who Invented Bitcoin

"Crypto" is slightly misleading as a prefix, because it means "secret or hidden." One might suppose they're called "cryptocurrencies" because no one understands what they are exactly, a mysterious virtual monetary system that exists only in cyberspace.

In fact, the prefix describes the technology that encrypts and protects identities and data, but the system is open-source, transparent, and therefore decentralized — and that's its strength. An investor who buys a bitcoin is assigned a personal key, impenetrable or encrypted in a way that is impossible to hack or reverse-engineer and that key becomes a kind of digital safe. The algorithms of the blockchain create a peer-to-peer decentralized banking system, without any middleman or data-hoarding corporate entity handling or authorizing the transactions.

"The beauty of bitcoin," Noble explains, "is the combination of technologies and the elegance and simplicity of that. It's the methodology with which you're able to backtrack the entire history of the bitcoin. There's no single groundbreaking piece of technology. It's the consensus mechanism for proof of work. It started as a nine-page white paper, released two weeks after Lehman Brothers crashed, saying, 'Here's how we're going to build digital currency, which is not reliant on any central bank.'"

The invention of bitcoin is credited to white paper author Satoshi Nakogama, with the caveat that no one knows if he's a real person or if the name represents a group of rebel programmers.

"Whoever wrote that white paper had to have a connection to the cypherpunk movement," Noble says. "They are aware of things that were firmly entrenched within that cypherpunk community. It was almost an act of anarchy, a political movement that believes central banks, politicians, etc. are able to be corrupt because they live in the shadows, behind obfuscation."

The nineties cypherpunk movement was a lot about obfuscation, about letting privacy be private, and about popularizing encryption.

"When you place financial transactions in the light of day, you don't need to know who those parties are. You just need to know the history of the transactions, and that will eliminate corruption," continues Noble. "The thinking was, centralized banks, and politicians, don't have the best interests of people at heart. Therefore, we need to find a monetary system that allows for peer-to-peer transactions. Something like the way music file-sharing evolved on Napster."

Some believe blockchain technologies represent a third stage of internet evolution. The first stage of open-sourced codes (HTML, email, GPS and so on) led to a second stage of centralized data where companies like Google, Facebook, or Amazon collect and own our digital information. Blockchain might mean we own and control our own data again.

I'm forever blowing bubbles

As with many attractive new financial opportunities, excessive zeal creates bubbles when overenthusiastic adopters let their optimism, or greed, best their common sense. Any chart graphing the history of the American economy will show a rollercoaster of manic speculation creating bubbles and busts, starting in 1716 when investors overvalued the potential for trade in French-held Louisiana. More recent would be the dot-com bubble of Y2K or the housing bubble of 2007. People who talk about bitcoin often refer to it as "the bitcoin bubble."

"But," Noble says, "there have been six or seven bitcoin bubbles already. Six or seven sudden devaluations. What causes that? Different things. It relates to emotion. The price is based upon potential. Not on, well, reality. It's like the stock market, where valuations are based on all the possibilities of what could happen to any particular company. And when you get new information that's unexpected, your stock prices change. Mount Gox was one of the first big crypto-exchanges that got hacked and collapsed the market."

Mt. Gox was a Japanese exchange, a place to connect buyers and sellers of bitcoin for a fee or percentage. Early on, Mt. Gox handled as much as 70 percent of bitcoin traffic — until it was hacked in 2014 to the tune of $460 million. Mt. Gox operating software was vulnerable to being overwritten, and only the owner could approve changes to the source code, which meant bug fixes took weeks.

"Bitcoin had hit a thousand dollars," Noble says, "but it fell to 200-plus after Mt. Gox. A lot of people sold. But when you read of a hack involving bitcoin, it's not the system. It's the centralized exchange. People go there to open an account, but then they leave their money in that account, where it becomes a target. And there's a hundred-something exchanges, and these get hacked all the time. It happens because people don't want to do the work it takes to set up their own wallets or buy cold storage wallets [secure offline USB drives]. People leave it in their exchange accounts and then you get hacked, the same way Target got hacked.

"People thought Mt. Gox was the end of bitcoin, but now we've seen that five or six times, something that challenges the existence and the utility of bitcoin in a major way. And each time, it corrects itself. The answer might be decentralized exchanges."

"Do you remember saying, 'I'll never put my credit card number in a computer?'"Â

Put on Your Jetpack and Google Glasses

If open-source transparency protects blockchain technologies like bitcoin by making them self-monitoring and self-correcting, it is also a vulnerability, where if anyone can start their own cryptocurrency, anyone will, and probably already has. There are now hundreds of cryptos, including Ripple, Ethereum, Dach, ZCash, Monero, Litecoin, and others, all vying for a piece of the pie (for an index of the best-selling coins, see coinmarketcap.com). This year, the state of Massachusetts blocked five companies (18moons, Mattervest, Pink Ribbon, Across Platforms, and SparkCo) from issuing their own ICOs, or initial coin offerings, in hopes of regulating a runaway market where disreputable start-ups issue coins to raise quick capital, or where pump-and-dump schemes artificially inflate coin values. Massachusetts is just one state, a relatively small jurisdiction in an economy that has no borders, at a time when buying cryptocurrencies is approaching mania. Noble thinks getting the SEC involved is not a bad thing.

"We may need regulation to prevent fraud," Noble agrees. "My research started in 2016, and eventually Dominick Oddo, a graduate student, and I pulled together a data set. It's pretty damning, the amount of fraud that happened in 2017. It's all marketing. This is the way to think about it — the dot-com craze is unfolding again but in a public spectrum. So all the fighting between venture capitalists that used to happen in Silicon Valley, jockeying for position to get into deals and find out about them first, to get your money in early to get the best valuation, pump it up, sell it — all that is unfolding in a public forum, in cryptocurrencies."

As with any tech innovation, predicting the future is fraught with peril. It's not hard to remember the false promises new technologies made in the past. Cable television was supposed to mean we'd watch TV without commercials. Word processing was going to mean paperless offices. Those of us who grew up with the space program are still waiting for our jetpacks and flying cars. Comedian John Oliver, in a piece on bitcoin, reminds us that someone thought, five years ago, we would all be wearing Google glasses.

"Yeah — that's not a thing," Oliver said.

"Do you remember saying, 'I'll never put my credit card number in a computer?'" Noble asks. "Or 'I'll never buy anything online?' Or 'I'll never buy something using a mobile phone?' Now, 7,000 websites store my credit card information, and I don't think twice about it. We don't know the future. What we're talking about is potential. That's all you can do. At a conference I went to, one of the top 10 people in the field said, regarding cryptocurrencies and blockchains, 'We're like where we were with the internet in 1991. We're pre-dial-up. We're dot-matrix printers.'

"To know what it is, you really have to bring a humility to your understanding, which is not easy, because you want to make a statement. You want to say something. But what we're talking about today is potential."

It's tempting to extrapolate the future by drawing a line from the past to the present and extending it.

Eight years ago, a man paid 10,000 bitcoins for two pizzas. On March 22, 2018, New York City real estate developer Ben Shoul sold two condos on Manhattan's Upper East Side for the equivalent of $2,360,000 in bitcoins, turning a virtual currency, existing only in cyberspace, into a place to live in real space.

Can the value of bitcoin keep rising? Probably yes.

Or no.

* Author's note: 10 minutes after interviewing David Noble, I received an email telling me how I could "jumpstart my bitcoin portfolio and become a millionaire." Probably just a coincidence.

"Do you remember saying, 'I'll never put my credit card number in a computer?'"Â

The Peter J. Werth Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation

Peter J. Werth sees UConn becoming the premier hub of entrepreneurial education. To help make it happen he announced a $22.5 million commitment to the University for a namesake Institute for Entrepreneurship and Innovation.

The Institute brings together student and faculty programs that foster entrepreneurship and innovation and that have the potential to create new products and new companies.

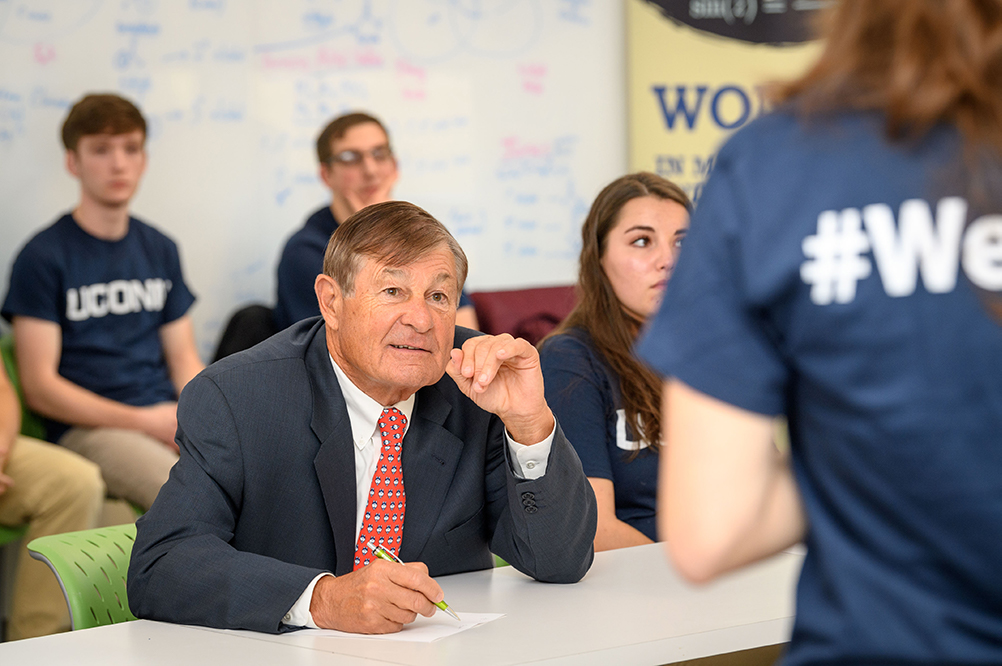

This is not just a School of Business endeavor. The Institute is actively seeking ideas from students and faculty members in every school and college, says director David Noble.

"If they have innovative ideas they now have a partner that can financially and administratively support their efforts," he says. "The Institute cannot be successful without a lot of great ideas and partners."

Begun at the end of last year, the University-wide collaboration has already produced fruit in the form of a 3-D printer for personalized medicine, a certification program for farms that promotes farmers' health, and a musculoskeletal loading device for sit-to-stand maneuvers for people with lower limb injuries.

Werth is the founder and CEO of ChemWerth, a drug manufacturing company based in Woodbridge, Connecticut.

"While I didn't attend UConn," said Werth in a statement announcing the donation, which was the second-largest in University history, "I have come to believe in its mission, and see the importance of creating opportunities for innovation at our state's flagship University."

Werth is the founder and CEO of ChemWerth, a drug manufacturing company based in Woodbridge, Connecticut.

"While I didn't attend UConn," said Werth in a statement announcing the donation, which was the second-largest in University history, "I have come to believe in its mission, and see the importance of creating opportunities for innovation at our state's flagship University."

Peter Morenus

Peter J. Werth listens to a presentation during an entrepreneurship and innovation huddle.

Tulip bulbs, anyone?

From Tracy: We love when people post their photos and other sighting information to our iNaturalist page…

https://www.inaturalist.org/projects/ct-bobcat-project