| Do Good, Feel Good |

Pioneering the new field of regenerative engineering — and championing social justice

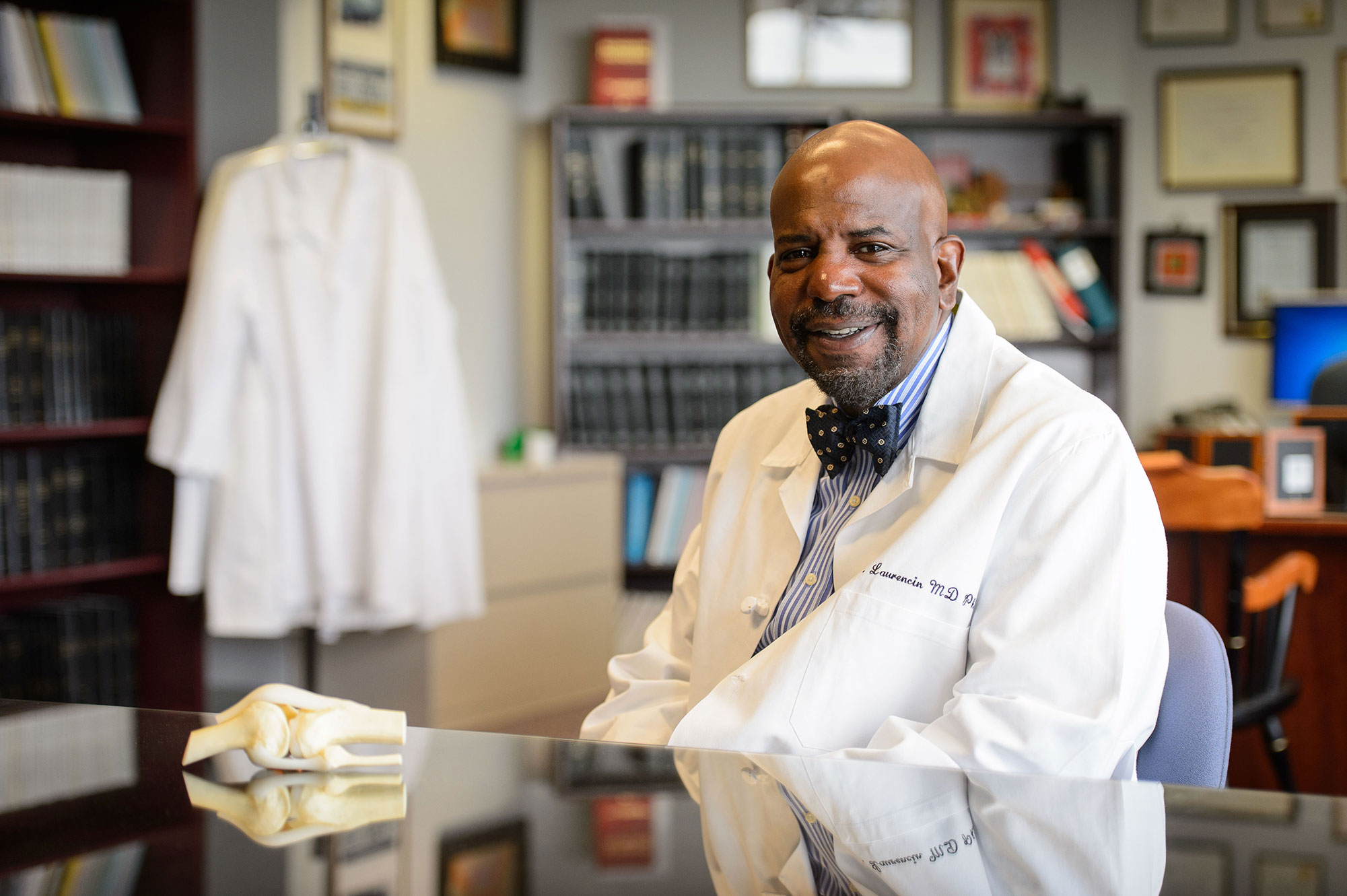

Photo by Peter Morenus

He has established preeminence in science, engineering, medicine, technology and social justice. A master of multiple fields, Dr. Cato T. Laurencin, holds UConn's highest academic title: University Professor.

Please tell us about yourself and how you got to where you are today.

I work at the interface of medicine and engineering and am also someone that is very much involved in issues of social justice. I grew up in Philadelphia and became interested in medicine at a very early age, and decided I wanted to become a doctor. I started college at Princeton, where I met people who were fantastic mentors in engineering. At that time, I was not quite sure how I was going to combine engineering and medicine, but I pursued chemical engineering.

When I completed college, I went on to medical school at the Harvard Medical School in Boston and partway through I decided to revisit my scientific and engineering routes. I met Robert Langer, who was a young assistant professor at that time and decided to join his laboratory. I subsequently took on a combined MD"“Ph.D. program combining work at Harvard with work at MIT. This program was unusual and I realized that to do a comprehensive job on both would take a long, long time!

With the support and help of Noreen Koller, who was a fantastic registrar at Harvard, I was allowed to move back and forth for my training, so I would do clinical rotations and then I would do work in the laboratory. This enabled me to complete my MD and Ph.D. combined in seven years, which really helped me on my journey because I became very, very used to working in both the clinical and research realms. I then began a residency in orthopedic surgery and opened my laboratory at MIT.

Since then I have been working in both areas; a common theme in all my research has been combining the principles of material science and engineering with physics and clinical medicine to allow us to be able to create new information and new science.

You have been recognized numerous times for your achievements in bioengineering. Could you talk about your work in this field?

I essentially defined what is now a new field — regenerative engineering, which is the convergence of technologies that we can utilize for the purposes of regeneration of complex tissues.

I first outlined this vision for the new field of regenerative engineering in 2012 and since then we have continued to work and expand the field. We now have a society called the Regenerative Engineering Society and our work has been successful in terms of developing new science, new technologies, and new ways of thinking for the regeneration of complex tissues and organ systems. We have been fortunate to be funded by the NIH Director's Pioneer Award and the National Science Foundation has awarded us two Emerging Frontiers in Research and Innovation awards for this new field.

You have recently been awarded the Herbert W. Nickens Award by the AAMC — congratulations! Please tell us briefly about that award, why you won it, and how that makes you feel.

I was very excited and very proud to receive the Herbert Nickens Award. It's the American Association of Medical Colleges' highest award for social justice and equity, and it recognizes the work that I have been involved in over the past almost 40 years in the area of social justice and equity.

It recognizes my efforts to create a fairer society for all in work that has ranged from boots on the ground programs seeking to increase the numbers of Black and Brown people working in engineering, science, and medicine, to larger programs such as the creation of The W. Montague Cobb National Medical Association Institute program looking at ways in which one can address disparities in health, medicine, and science for Black people, to launching a new journal — the Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities — which is now the leading journal working in the space, to our new work in terms of Chairing the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine Roundtable on Black Men and Black Women in Science, Engineering and Medicine.

I have been involved in a broad gamut of endeavors that have at their core the aim of making the U.S. and the world a more fair, just and equitable society.

We are all in need of a little happiness and a little inspiration lately, so we've devoted this issue of the magazine to stories of just a few of the many UConn faculty, staff, students, and alumni who spend their days doing good in the world, making it a better place for all of us.

You have received singular honors for your years of work. You were the first individual in history to receive both the oldest/highest awards from the National Academy of Engineering (the Simon Ramo Founder's Award) and the National Academy of Medicine (the Walsh McDermott Medal). The American Association for the Advancement of Science recently awarded you with the prestigious Philip Hauge Abelson Prize for your innovative research, contributions to national policies regarding science, and for dedication to supporting diversity in the field. How will regenerative engineering shape the future?

At the Connecticut Convergence Institute our main focus is on regenerative engineering, which as I mentioned is defined as the convergence of advanced materials sciences, stem cell science, physics, developmental biology, and clinical translation, for the regeneration of complex tissues and organ systems. Our Institute aims to regenerate human limbs, not robotic limbs but rather real, organic, flesh-and-blood ones that grow on the person receiving treatment. This type of breakthrough will have a tremendous impact on global public health and in the lives of those with amputations due to bone cancer, diabetes, dangerous infections, trauma accidents, or children born with missing or impaired limbs.

The ultimate goal of the Hartford Engineering A Limb (HEAL) project, under active research in my laboratory, is aimed at helping wounded warriors as well as others who have lost limbs or experienced joint damage. Other patients who could benefit from the future breakthroughs are those with amputations due to bone cancer, diabetes, dangerous infections, or trauma accidents, or even children born with missing or impaired limbs.

What would you say are the main challenges still hindering equity in healthcare?

Our main challenge in terms of equity for Black people in both the U.S. and the world is the persistence of racism. We know that there are excess deaths each year of Black people linked to racism and we have known this for a very, very long time — this is not new news. In the 1990s, the National Medical Association had a consensus report examining racism and its effects on health and the creation of health disparities. The National Academies followed up with a study called "Unequal Treatment," which examined the unequal treatment of Black people and others in the U.S. and found racism to be a primary reason why this is happening.

Recently, we have seen the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor garner widespread media attention. This injustice translates to the medical establishment, too, in terms of medical care, which translates to higher mortality for Black people. That is the major challenge we have to address in terms of healthcare and something that I am very passionate about.

We recently made the case for why we need to see more Black professionals working in medicine, along with science and engineering. On the medical side, Black physicians treating Black patients obviously do not exhibit the levels of unconscious bias and conscious racism that take place among white physicians and some new studies — for example in Covid-19 — have suggested that clinical outcomes are improved where Black physicians have taken care of Black patients.

So what challenges are still faced by Black and Brown students who aspire to careers in STEM industries, such as healthcare?

Number one is that there are so many systemic racism issues. It was extreme when I was growing up — I still remember walking into a classroom at MIT and having a professor block me from coming into the door. Is it still this extreme? Probably not as blatant, but just as damaging.

As an active mentor helping address this, what are your top tips for others hoping to be good mentors?

I was very fortunate to win the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Math and Engineering mentorship from President Obama and the American Association for Advancement of Science Mentor Award, so mentoring is a big component of my life.

I think for mentors it is important that there is a dedication to that individual and to their long-term future. I have been fortunate to have mentorships that have been lifelong; I am still in contact with people I have mentored who are now full professors and chairs or deans. I think it is also important that the mentorship is a two-way relationship — meaning that there are expectations from both the mentor and the mentee. The mentees have to follow up with and listen to their mentors. It is not necessarily that the person has to agree with what their mentor says, but there has to be a clear relationship in which the counsel or guidance is provided and has been well thought through. Finally, there has got to be an open dialogue about successes, setbacks, and plans.

You touched earlier on studies showing the availability of Black physicians reduces unconscious bias and improves care. Do you think that a representative workforce is requisite for equitable healthcare?

Yes, I think you do need to have a representative workforce in order to be able to have equity in medicine, for a number of reasons. Number one — because, as we alluded to, when you have Black and Brown physicians, you reduce the levels of unconscious bias and racism in the system as a whole and that results in better quality of care. Number two is that to a great extent the under-representation of Black physicians in medicine right now is a symptom of a system that has at its roots systemic racism.

One marker for how we progress is to examine the numbers of Black people who are in medical school. We had a historic low in terms of Black men in medicine around 2014"“2015. Those numbers have rebounded a bit, but that shows that even in a world in which we talk about diversity and equity, such a phenomenon can happen. That's why I published my piece "The Context of Diversity" in the journal Science. You cannot think of diversity as an old Kumbaya general feeling. We have to look at what's happening with specific groups and with the specific challenges that are taking place in specific groups. With Black people, especially in the U.S., we know that racism plays a role in every aspect of their life.

I wrote a paper recently on racial profiling as a public health issue speaking to how racial profiling by police in America has serious health effects. This is an area that really needs to be addressed.

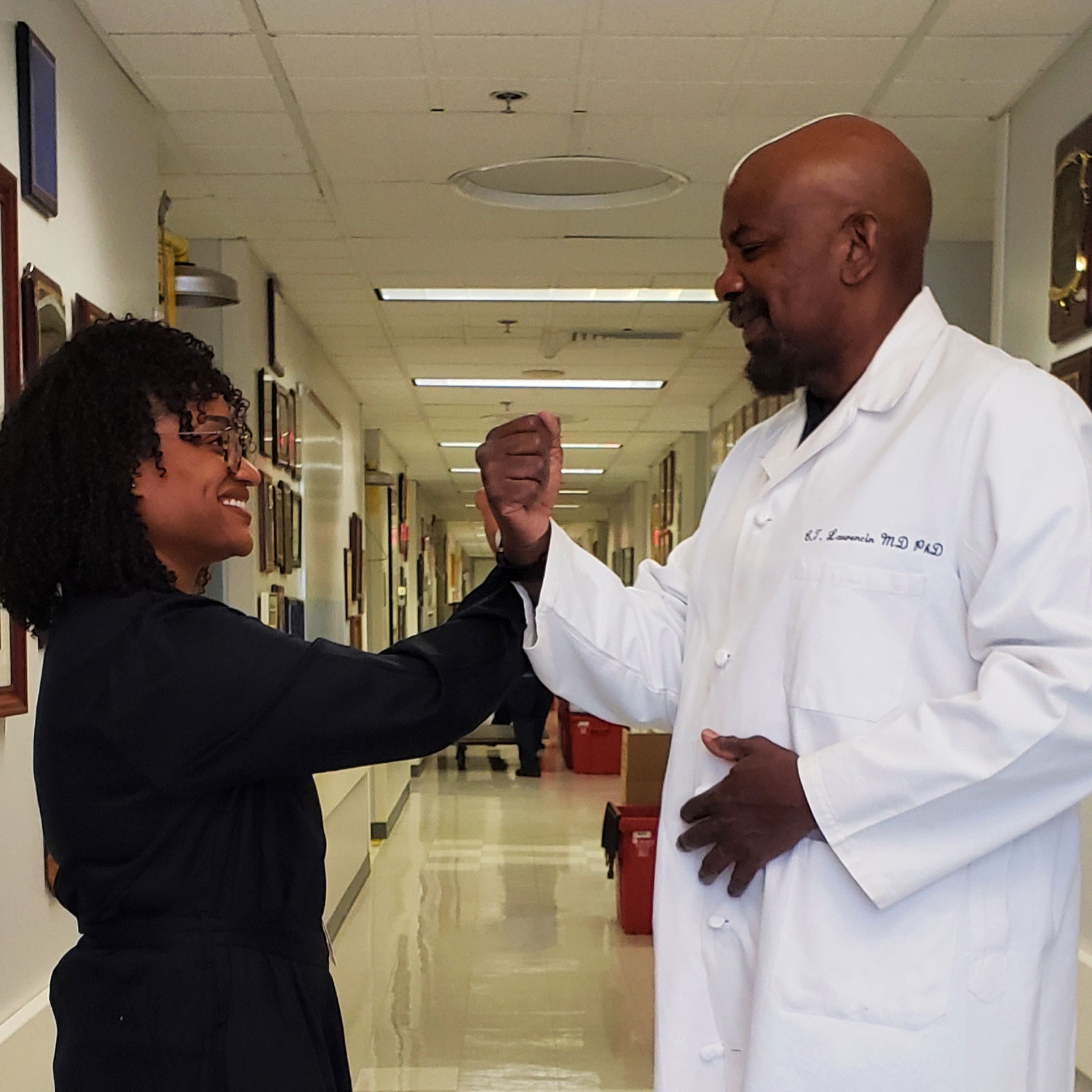

Dr. Laurencin's interest in social action led to the creation of the Laurencin-McClinton Greeting (LMG) in conjunction with his research fellow Dr. Aneesah McClinton. The handshake alternative was created in an effort to reduce human contact and protect public health. The LMG was published in Science under the editor's blog.

You've done much for the state of Connecticut. You were the faculty architect for Bioscience Connecticut, which revamped UConn Health, and even serve as a Commissioner for Boxing for the state. You've been awarded the Connecticut Medal of Technology and Innovation for your work not only in research, but in entrepreneurship. You have a large social justice footprint in the state. You serve on the Connecticut Racial Profiling Prohibition Advisory Board and you were recently named a Connecticut Magazine Healthcare Hero. Tell us about your work that earned you that title and what your vision is for the future.

In the "Healthcare Hero" article I discussed how and why the coronavirus was and still is disproportionally affecting Blacks. I recall that when Covid-19 first hit, there was a myth of Black immunity that was circulating on the internet and social media, so I set out to examine that because I was really concerned if that misinformation got out it could be disastrous for the Black community.

I published the first peer-reviewed study in the nation with these findings in April. It exploded the myth and created an early warning that the disease could be particularly bad for the Black community.

It's important to understand that the reason the levels that we're seeing are this high is because of the history of discrimination that has taken place in this country.

When thinking about remedies for the issue at hand, I developed the concept of the IDEAL Pathway to creating a just and equitable society. Currently, we're in a world of discussions about diversity, inclusion, and equity. While we have had some gains in these areas, they have not really sufficiently addressed the issues of racism that we see in this country. So my belief is that we need to move to inclusion, diversity, equity, anti-racism, and learning (IDEAL). Understanding ways in which Black people are affected by the specific kinds of racial discrimination called anti-Blackness. Understanding the history of Black, Indigenous, and all people of color. Moving from ally to what I would call a ride-or-die partner in the anti-racism movement — these are some of the ways that I believe learning can be used in a constructive way to bring about the ideal pathway to move forward.

Finally, what have been some of your proudest moments during your career thus far?

The proud moments are too numerous to count. I am blessed and highly favored. The moments surrounding my family (meeting and falling in love with my wife, and the birth of my children probably count as the best moments).

Speaking of moments, I want to share some of my philosophy. There are actually three "most important" dates of your life. They are the day you are born, the day you realize your purpose in life, and the day you are truly carrying out your life on purpose.

For me, starting the new field of regenerative engineering, taking care of patients as a surgeon, working for social justice, and mentoring the next generation, all while doing the most important thing: staying connected to my family, my values, and my God — collectively represent my purpose.

A life on purpose is where I am, which is the ultimate goal.

Portions of this interview originally ran in the journal BioTechniques.

Leave a Reply