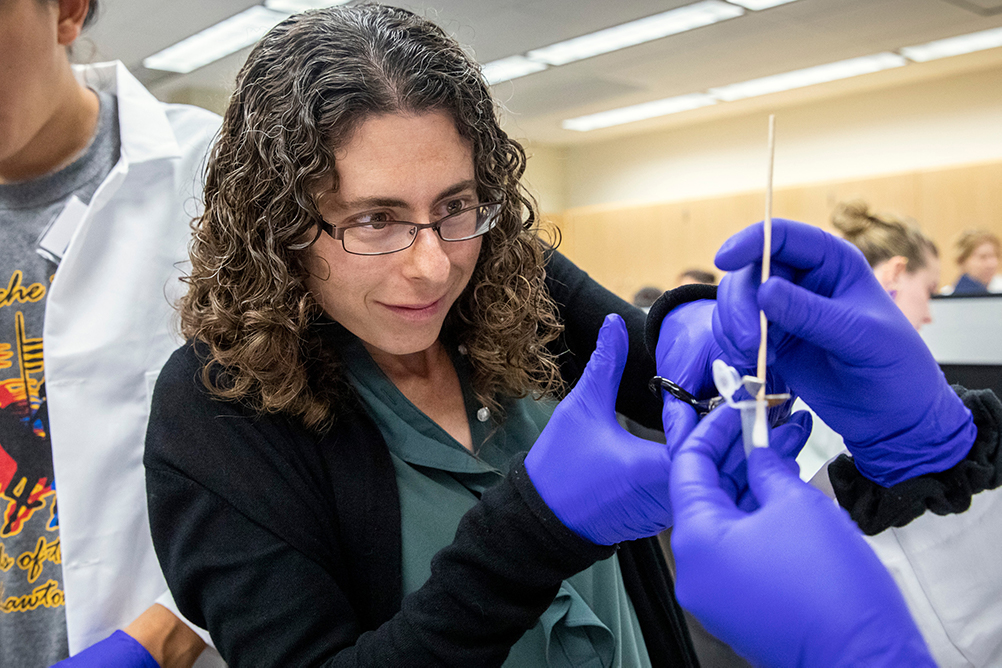

Anthropology professor Deborah Bolnick analyzes ancient DNA in a state-of-the-art Clean Lab in Storrs where her work is, among other things, helping to shed light on Native American histories.

By Christine Buckley

Photos by Peter Morenus

T

To set foot in UConn's Ancient DNA Lab, your first stop is the antechamber.

You hear a whoosh of HEPA- filtered air as you open the shatterproof glass door that is flanked by square white flypaper-like sticky mats, which snatch dust from the soles of your shoes.

Step into the anteroom, instructs laboratory head Deborah Bolnick, and place your belongings in a drawer marked "Outside Stuff," next to the bottles of cleaning liquid labeled "DNA Away."

Don a Tyvek bodysuit, a surgeon's hat, sleeve covers, shoe covers, face mask, and one pair of latex gloves. Make sure you put on a second pair once you're inside. Because your DNA is on the first pair.

"Ancient DNA research is hard," says Bolnick, a professor of anthropology and member of UConn's Institute for Systems Genomics.

To set foot in UConn's Ancient DNA Lab, your first stop is the antechamber.

You hear a whoosh of HEPA- filtered air as you open the shatterproof glass door that is flanked by square white flypaper-like sticky mats, which snatch dust from the soles of your shoes.

Step into the anteroom, instructs laboratory head Deborah Bolnick, and place your belongings in a drawer marked "Outside Stuff," next to the bottles of cleaning liquid labeled "DNA Away."

Don a Tyvek bodysuit, a surgeon's hat, sleeve covers, shoe covers, face mask, and one pair of latex gloves. Make sure you put on a second pair once you're inside. Because your DNA is on the first pair.

"Ancient DNA research is hard," says Bolnick, a professor of anthropology and member of UConn's Institute for Systems Genomics.

It's easy to forget that this shiny, four-room, white-and-chrome laboratory stacked with state-of-the-art equipment and designed to annihilate stray strands of modern DNA overlooks UConn's Great Lawn from 90-year-old Beach Hall. Or to forget that the Great Lawn itself — and the whole of UConn — is the historical territory of Indigenous peoples, including the Mohegan, Mashantucket Pequot, and Nipmuc tribal nations.

But tucked into a deep freezer in the DNA sample prep wing are the ancient remains of Indigenous people — tiny extracts from teeth and bone — unearthed from burial sites across the Americas and entrusted to our stewardship. They're waiting to be sequenced, analyzed, and interpreted to help contemporary communities understand how their ancestors lived and moved across this land — and how the environment shaped their evolution.

In an age where DNA testing is rampant, Bolnick is striving to use science to understand the past experiences of Native Americans and, further, to empower Indigenous people to create and use such data themselves.

- The Accidental Anthropologist -

Bolnick grew up in Kansas City, near a starting point for the Santa Fe trail. She loved history in high school, especially American history, and happily set off to Yale looking forward to "never again taking another science class." But her first course in biological anthropology hooked her.

"It's a science that is situated historically," she describes. "It's drawing on history, literature, and culture and combining that information with human DNA to understand something about our histories."

While in graduate school at University of California, Davis, she learned how ancient DNA analysis works in the lab of David Glenn Smith.

It goes something like this: Being as sterile as possible, use specialized chemicals or minimally invasive drilling techniques to extract DNA material from an archaeological sample of human remains, most often tooth or bone, less often hair or even feces — Bolnick relays that thousand-year-old rehydrated coprolites smell just like modern poop.

The older the DNA is, the more it will have degraded into small pieces, so prepare DNA "libraries" and use the polymerase chain reaction (PCR "“ a technique that revolutionized genomic science in the 1980s) to tag and replicate the DNA into thousands of copies.

Run that DNA on a next-generation sequencer, which determines the order of A's, T's, C's, and G's on each strand.

Finally, using bioinformatic techniques, compare the sequence output, reported as long strings of these four letters, to genome banks containing data from people around the world. Any similarities or differences can suggest that individuals or groups may be related or may have evolved over time.

"When you combine it with oral histories, historical documents, or archaeological evidence, ancient DNA can be another data point for us to learn about the experiences people have had in the past," she says. "That historical angle is what makes it interesting and exciting for me."

Bolnick is striving to use science to understand the past experiences of Native Americans

- Why It Matters -

At graduate school for anthropological genetics at the University of California, Davis, Bolnick also became interested in a population of ancient Native Americans who had been interred in burial grounds in Illinois and Ohio. She wanted to determine if patterns in the archaeological record and genetic record both suggested the same history of interactions for those groups.

Many archaeologists at the time claimed that these Indigenous peoples had no living descendants, a fact that, even while she was collecting data, began to bother Bolnick.

"It was interesting, but I struggled with the question of: Who cares? I thought, 'These are people who lived a long time ago. They don't give a damn what I'm doing. Why does this matter?'"

She and Kim TallBear (Sisseton-Wahpeton Oyate Dakota), who was then a Ph.D. student at the University of California, Santa Cruz, began work on a project advocating for science policy surrounding the implications of genetic ancestry testing for Native Americans.

Membership in tribal nations is a cultural, political, and legal question that can't be determined by genetics alone — it involves tradition and lineage that have nothing to do with genetics. Just ask Elizabeth Warren, whose decision to undergo DNA testing for Native American heritage would dog her in the leadup to the 2020 presidential election.

But, if abused, could DNA testing force communities to recognize new members based solely on those results? In cases of adoptions or marriages outside of Indigenous communities, could it sever traditional ties of cultural kinship?

Bolnick, TallBear, and their colleagues published an often-cited policy article in the journal Science. It was a cautionary note for the scientific community: Be careful of the promises made related to genetic testing, and be sure to consider all pieces of evidence, not just scientific ones, to draw conclusions about community groups.

"We must weigh the risks and benefits of genetic ancestry testing, and as we do so, the scientific community must break its silence and make clear the limitations and potential dangers," she and her coauthors concluded.

- Unintended Consequences -

After moving to a faculty position at the University of Texas at Austin, Bolnick developed ancient and modern human DNA projects across the Americas. She honed nondestructive practices to extract DNA from ancient bones and teeth so the remains could be repatriated intact to native groups. With graduate students, she conducted analyses showing that Aztec and Spanish conquests altered the genetic makeup of inhabitants of Xaltocan, Mexico. She published genetic evidence suggesting common ancestry for all living and ancient Native Americans. Her work was gaining renown in the scientific community.

Then, in 2010, she got a call from an annoyed person. Marcus Briggs-Cloud (Maskoke), then a graduate student in divinity studies at Harvard, remembers being approached on campus by a man with a fistful of cotton swabs who asked if Briggs-Cloud would collect DNA samples of his community members for National Geographic.

Definitely not, Briggs-Cloud snapped.

Weeks later, his friend Ana Sylestine (Coushatta tribe of Louisiana), told him she had had her DNA sampled. He was not happy.

"I started chastising her, saying that genetic research is so problematic, such a colonial project," he remembers. "She said that maybe I should have a conversation with the researcher. I said, 'Yes, I think I will.'"

Briggs-Cloud called Bolnick, and they had a two-hour conversation in which a defensive Briggs-Cloud voiced his distrust of Western scientists who disregard Indigenous culture.

She listened and agreed.

"Deborah was totally open to my scrutiny of academia," says Briggs-Cloud.

Soon they had another two-hour conversation. Over the next two years they spoke at intervals, each learning the other's perspective. Briggs-Cloud began to think that there was something different about this scientist.

Meanwhile, another former UC Davis labmate of Bolnick's, anthropological geneticist Ripan Malhi, had been working to establish a program to address these issues. The summer internship for Indigenous peoples in genomics (SING) is a week-long immersion in scientific training and ethics discussions at the University of Illinois, designed to empower Indigenous people to get involved in human genetics research.

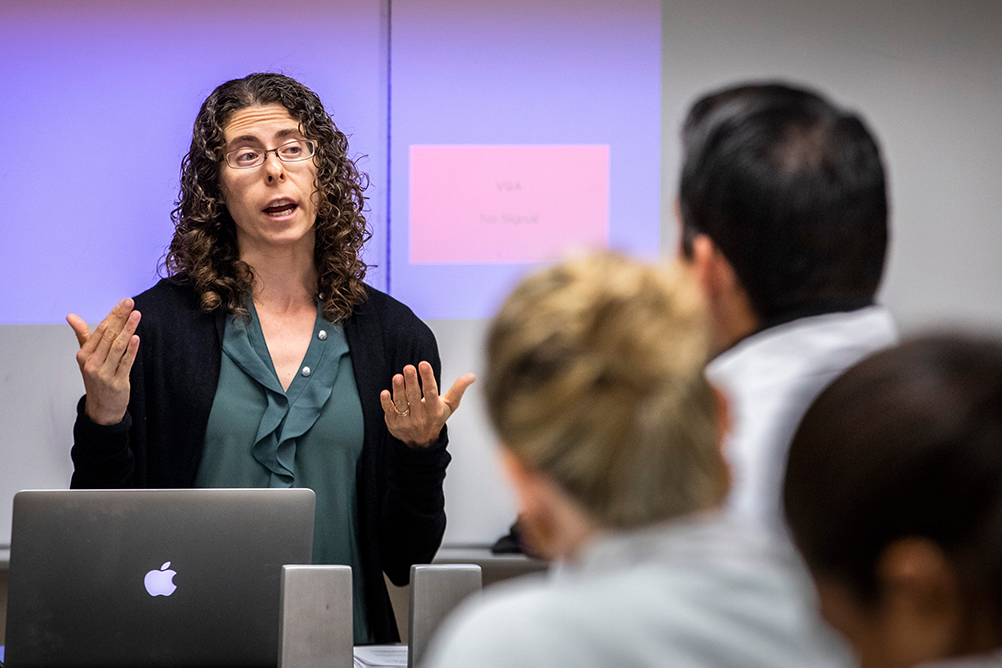

At SING 2013 Briggs-Cloud, Bolnick, Sylestine, and the 22 other participants and faculty performed DNA extraction and analysis, discussed scientist"“Indigenous community relationships, and learned from one another.

Briggs-Cloud says he came out with a revolutionized understanding of the scientific process and filled with feelings of solidarity with other Indigenous people struggling with genetics and their identity. But he still had questions.

"I was feeling like, this is all lovely, but how is it benefiting Indigenous communities at a localized level?" So Bolnick asked him: What would you propose?

Bolnick leads a workshop at the 2019 summer internship for Indigenous peoples in genomics, known as SING.

Photos by UI News Bureau/Fred Zwicky

- Matchmakers -

Briggs-Cloud wondered about helping certain Indigenous people rediscover their clan identities — likely lost through forcible displacement from ancestral homelands. Bigger than families but smaller than tribes, clans are central to tribal identity, determining the family you belong to and your place in the community.

Clan membership in some communities is passed down through an individual's mother, so Bolnick wondered if analyzing mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited from the mother, might be able to trace that information. A new project emerged. Take wide-ranging samples of living Indigenous people who know their clan membership. Look for similarities in the genomes of groups identifying with those clans. Then compare the DNA of people who don't know their clan identity to this library.

Today, Briggs-Cloud, Bolnick, and their collaborators have established frameworks for understanding the genetic variation in and among clans in several communities in the southern U.S. Briggs-Cloud has collected the samples, and they analyzed the data together.Â

Bolnick does not name the communities she works with to protect their anonymity. But Briggs-Cloud says he has watched an individual who previously did not know where to sit in an arbor during a tribal ceremony cry tears of joy when, after learning his likely clan identity, he walked to his place in the ceremony.

It is a healing moment, says Briggs-Cloud, that he never thought he would see. "If not for Deborah, I would have remained an enemy to the academic enterprise. She was willing to take me on without knowing anything about genetics. After more than a decade of working together, I can confidently say she is one of a kind."

Briggs-Cloud, Sylestine, and one of Bolnick's first graduate students, Austin Reynolds, along with other colleagues, released another decade- long analysis last year. That article showed that influxes of diseases like smallpox, measles, influenza, and cholera after European contact likely influenced genes associated with immune function in Native American populations — in the same way that Alaskan Natives have developed genetic variants adapted to cold climates.

In each case, Indigenous partners orchestrated the collections, and the data set took almost 10 years to create and analyze. Reynolds chalks this up to Deborah's unending but dogged patience.

"Deborah is a humble listener," says Reynolds, who is now a post-doctoral researcher at UC Davis. "She listened even when I was an overexcited undergraduate with lots of wild ideas. She really showed me that you could use scientific methods to learn something about human culture."

- Justice For All -

Over the years, word of Bolnick's passion for genetics for social justice has spread, garnering her a reputation as a person who wants to do work to empower underrepresented populations. There are only about a dozen ancient DNA labs in North America, she says. So she regularly gets requests for DNA analysis.

In November 2014, excavation of a parking lot for a new wing on the Baldwin Hall building at the University of Georgia turned up human remains, which when completely unearthed totaled 105 unmarked graves adjacent to a known historic cemetery site.

While the university asserted that the bodies were likely of European descent, the Athens, Georgia, community cried out.

"The Athens African American community said from the beginning, 'We think this is where our enslaved ancestors were buried,'" notes Bolnick. "They were ignored, forgotten, erased."

So when Bolnick's colleagues in the University of Georgia anthropology department asked for her help, she accepted.

"Racism and discrimination have material consequences on the bodies of marginalized people, which in turn influences their genetics."

Her lab's analysis of mitochondrial DNA from about 40 individuals revealed that nearly all had West African maternal ancestors, and since they were buried around 1830, it's very likely they were enslaved.

In a similar incident, in February 2018, the remains of 95 individuals were unearthed in a project to build a new school in the town of Sugar Land, Fort Bend County, Texas.

The "Sugar Land 95" raised controversy, with the local African American community protesting as the bodies were re-interred at a nearby cemetery in 2019, before DNA testing was completed.

Bolnick is currently working under an agreement with the University of Texas at Austin's Texas Archaeological Research Laboratory, which curated the remains, to analyze DNA from the Sugar Land 95.

Graduate student Samantha Archer is hard at work analyzing these remains of post"“Civil War convict laborers to gain greater insight into their identities, their lived experiences, and their relationships to one another and present-day members of the local community.

- "Reorient How We Do Science" -

Human genetic data is easily accessible and often discussed in the 21st century. People think about their DNA as a fixed, inherited part of their ancestry that doesn't change and is a be-all, end-all. They think it can tell you everything about where you have come from, who you are, and who you will become.

But Bolnick hopes that her work shows people that nongenetic factors matter — that historical events and social processes and lived experiences shape our biology and our DNA too.

"We think in terms of genetic determinism, that our biology determines our behavior, features, physical attributes, personality, identity . . . That's B.S.," Bolnick declares. "More often the genetic makeup is being shaped by the worlds we experience and that our ancestors experienced."

She notes that in the modern world, lived experiences like racism and discrimination have material consequences on the bodies of marginalized people, which in turn influences their biology and how their genes are expressed.

If there is one metric that Bolnick uses to determine her success, it's helping to, as she puts it, "reorient how humans do science."

Science has had a long history of being closely tied to racism and oppression and discrimination, she says, and bolstering the institutions in our society that harm marginalized people.

We need to work hard to undo those connections, she says.

"We should strive to do a different kind of science," says Bolnick. "We need to take tools we have and apply them to questions of interest to people who have been historically marginalized by this discipline. If I can help to facilitate making those shifts across science, to me, that's a success."

Quite interesting on several ways. First, a former Beach Hall site of my geography classes in the 1960s, great to see that Beach Hall continues as a special UConn asset. Second, my interest in Indigenous people stemming from my various family residential homes in Oklahoma, Venezuela, California, New York and Connecticut brought me in contact with various peoples. And, most of all, to learn of a incredible person with a balanced approach to a special and shared skill!