The Shape of Storrs

Geology professor Robert Thorson says UConn is UConn because glacial ice slid by 20,000 years ago and shaped the landscape that today includes our iconic Horsebarn Hill

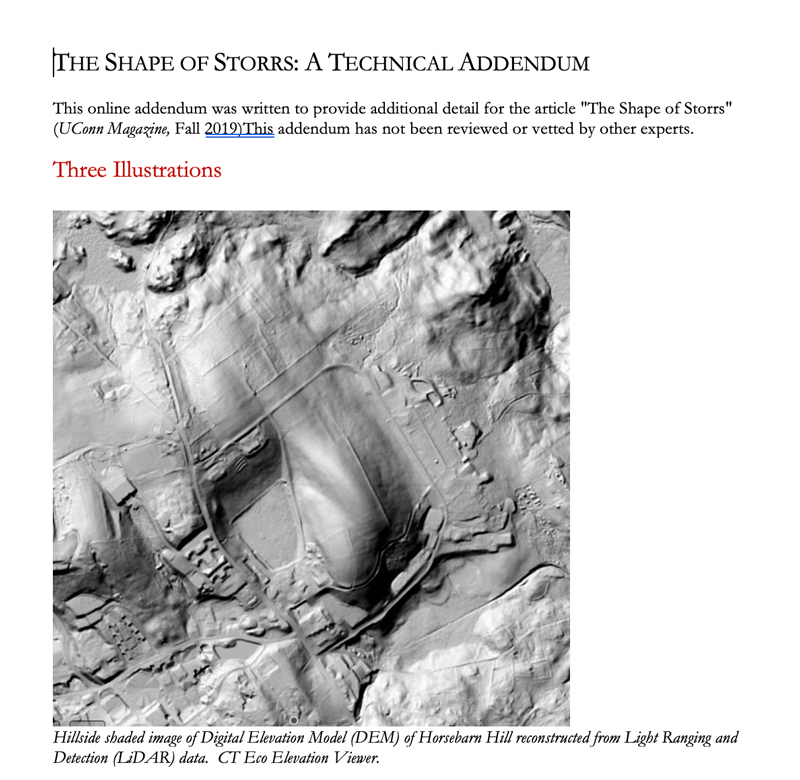

By Robert Thorson

Paintings by Blanche Serban

Photographs from the University Archives

Cresting the wooded hill on Highway 195, we began our southerly descent into Storrs. Abruptly, our eastern horizon expanded to reveal the gracefully curved profile of Horsebarn Hill. That smooth silhouette, that whaleback shape, that green ellipse is the single most beautiful thing on the UConn campus.

That's what I decided during my first visit to Storrs, which I made to interview for the professorship I still hold. Within a month, I would be uprooting my Alaskan family to teach at a red-brick university with the most beautiful skyline in New England. During the decades to come, Horsebarn Hill would become my topographic tonic. When life got rough, its sweeping curve smoothed out my sharp edges. When I felt down, its high profile lifted my mood. When I felt confined, the panoramic view from its summit reminded me that I'm surrounded by a vast expanse of rural woodland beauty.

Today, Horsebarn Hill lies beneath a blanket of atmosphere. My sights and sounds are of clouds, birds, breezes, and cattle making milk for Dairy Bar ice cream. Yet scarcely 20,000 years ago, that same hill lay beneath a blanket of glacial ice sliding southward. My only sight would have been of perpetual darkness. My only sounds would have been mechanical — the grinding, crushing, scraping, and shattering of rock residues being pulverized, and the smearing noises of a landform being shaped by glacial erosion. These cold dark acts of creation gave rise to the rich moist soils and smooth slopes that attracted pioneering farm families of the late 17th century to settle here, and the farm educators of the late 19th century to plant the seeds of UConn Nation.

Horsebarn Hill symbolizes that creation story, making it my candidate for UConn's most essential icon. It overlooked the birthing ceremony of Storrs Agricultural School in 1881 and overlooks our great university today. The gilded cupola of Wilbur Cross (1939) marked our metamorphosis into a liberal arts university, and the silver dome of Gampel Pavilion (1990) marked our emergence as an athletic dynasty. Both are splendid icons. But let's not forget that these architectural achievements came much later and were built on the same stuff from which Horsebarn Hill was made.

1925 aerial biplane photograph shows Mirror Lake to the right and Horsebarn Hill to the left.

Being a teacher, I know that when learning something challenging, it helps to kick-start the process with something simple. So, before I get down to the nitty-gritty of UConn's creation story, I'll offer a parallel example from America's Deep South. During the U.S. presidential elections in 2016, an anomalous swath of blue Democratic counties supporting Hilary Clinton curved through a red sea of Republican counties supporting Donald Trump. Though this anomaly puzzled political scientists sifting through surface data, the geoscientists went down into their earthly cellar to find an answer. This so-called "black belt" of politics was the statistical expression of a demography dominated by African American voters, which was a historical legacy of early 19th century chattel slavery, which aligned with a belt of soils perfectly suited to cotton, which developed on a black belt of marine shale deposited about 75 million years ago when sea level was much higher than it is today. Modern American politics traces back — step by step — into deep time.

A similar linkage of historical contingencies took place in Storrs. But instead of a black belt of clay-rich Confederate soil ideal for cotton plantations, we had a rolling gray patch of loamy Yankee soil ideal for the growth of grass, the anchor for New England's agricultural economy. Grass is what livestock graze upon in open pastures; it is the hay cut for winter fodder and the cereal grain we grind to make our daily bread out of corn, rye, wheat, oats, or barley.

The barn sits watchful by the road (or The Barn), oil

White spirals build the air over the hill (or White Spirals), oil

Light and shadow play their drama in stillness (or Purple Clouds), oil

UConn's brotherly benefactors Charles and Augustus Storrs donated the farm on which our main campus would grow. Their bucolic childhood landscape was lovingly described in general terms by the Reverend Timothy Dwight's "Travels in New England and New York" (1820). When reading every page of this three-volume doorstopper 20 years ago, I discovered why such land was so prized:

The hills of this country and of New England at large, are perfectly suited to the production of grass. They are moist to their summits. Water is everywhere found on them at a less depth than in the valleys or on the plains. I attribute the peculiar moisture of these grounds to the stratum lying immediately under the soil, which throughout a great part of this country is what is here called the hardpan.

The hills Dwight refers to are mainly drumlins, a Gaelic word for "rounded hill." They're moist enough to maintain good pasture during drought, fertile enough to sustain demanding crops, and smooth enough to allow easy access in every direction. This smoothness is what makes Horsebarn Hill a popular sledding destination. And for a while there was even downhill skiing. When on field trips, my students interpret its derelict towrope as evidence for climate change.

The earliest aerial and hilltop photos of UConn — some, like the one shown at right, taken from biplanes with cloth wings — reveal that the historic campus lay within a cluster of rounded hills cast from the same mold and aligned in the same direction as Horsebarn Hill. Our first large campus building — the wood-framed Old Main (1890) — was perched on the crest of one of these low, streamlined eminences. Surrounding it were rolling pastures crisscrossed by fieldstone walls. Our first large, red-brick building, Storrs Hall (1906), was aligned with the southeasterly glacial grain, initiating a layout grid for future buildings parallel and perpendicular to the rake of the ice.

1908 photo shows Jacobson Barn just right of center at the top of the hill.

UConn's Great Lawn, which sweeps uphill from Highway 195, is the eastern flank of a formerly rounded ridge — its crest was flattened for Beach and Gulley halls and the Family Studies Building. During my pedestrian commute, I walk up and down that hillside between home and office, seldom failing to give thanks to its icy maker.

Dwight's hardpan is what we now call till, a Scottish word for a "kind of coarse and obdurate land." Actually, it's a special type called lodgment till, a sediment pasted to the land like crunchy peanut butter being smeared on a firm piece of bread. In the glacial case, the material being smeared was a stiff mixture of pulverized rock and uncrushed fragments (the crunchy bits) being lodged to the land surface under great pressure by slowly moving ice. In Connecticut, thick patches of lodgment till are generally restricted to the rounded hills decorating elevated plateaus. Our state's most extensive patches create especially scenic inland towns like Litchfield and Woodstock.

In 1698, the founding patriarch of UConn Nation, Samuel Storrs, pioneered one of those plateaus on the drainage divide between the Fenton and Willimantic rivers. Having emigrated from Nottinghamshire, England, in 1663 to the dry, sandy, lowland soils of Barnstable, Massachusetts, Sam eventually picked up and moved to the largest patch of lodgment till in a wilderness that would soon become the town of Mansfield. Generation after generation of his family practiced an agricultural economy that historians call mixed husbandry. I prefer the term livestock tillage because it's gender neutral, free from any suggestions of bigamy, and it emphasizes grass-fed livestock via pasturing and hay-making for cattle, sheep, and horses, and the tillage of grass for cereal grains.

To a garden shovel, lodgment till replies with a firm thud, often accompanied by a clank of stone. Like pottery clay fresh from the package, the till is weak enough to have been molded by passing ice into a smooth mathematical curve but strong enough to withstand thousands of years of gully erosion. Till soils keep pastures verdant, even through the dog days of August. Rain and snowmelt soak easily through the root-stirred topsoil but are blocked from infiltrating down to the water table by hardpan at shallow depth. The soil is loamy enough to retain copious water for plant roots, and highly fertile because it contains billions of crushed mineral grains that release and bind nutrients for plant growth.

"During the decades to come, Horsebarn Hill would become my topographic tonic. When life got rough, its sweeping curve smoothed out my sharp edges. When I felt down, its high profile lifted my mood."

When I moved to New England from Alaska, UConn met all three of my geographic job search criteria in ways that other universities and colleges could not. I wanted to live north of the glacial border, accessible to the ocean, and at some distance from the nearest metropolis. Storrs met all three criteria, the last being the most restrictive. Though nearly perfect for livestock tillage, the features of this rolling plateau deterred urbanization: It was too high, too inland, too far from natural transportation corridors, and its streams were too small to power industrial mills.

The result was a rural patch of good grazing surrounded by rougher, rockier, more steeply sloping soils. In 1698, this inland island attracted a pioneering English yeoman and his family. In 1881, their successful descendants created Storrs Agricultural School. In 1893, that school was upgraded with federal funds to become the state's land grant institution, Storrs Agricultural College. In 1899, that name was broadened to reflect the new statewide mission, becoming Connecticut Agricultural College. By 1939, after four decades of construction and growth, the college's name was broadened to the University of Connecticut. Since then, its enrollment, mission, and geographic breadth have gone global. That success traces back — step by step — into deep time.

Given the frenetic pace of cultural and environmental change today, it is hard to believe that Horsebarn Hill, less than a century ago, was one of a cluster of streamlined hills on a pasture campus crisscrossed by fieldstone walls. Since then, the walls have been hauled away into oblivion, and the hills flattened to make room for the masonry buildings, lawns, and paths of our beautiful, historic campus. Yet throughout it all, Horsebarn Hill remained largely untouched. Its graceful skyline curve and its ornament of old fieldstone walls symbolize the creation story of UConn Nation and the almost magical substance from which it was made.

Professor Thorson would like to note that he penned this love letter to Horsebarn Hill in celebration of the new Department of Geosciences in UConn's College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

Hear Professor Thorson speak about UConn's Origin Story, Horsebarn Hill, and The Shape of Storrs on Dec. 7 at 2 p.m. as part of the Connecticut State Museum of Natural History public lecture series. Find more information at mnh.uconn.edu Calender of Events.

Hi and thanks,

Dr. Thorson took us on a remarkably entertaining walk through Pleistocene “deep time” to bring everything forward to the Holocene and even into direct contact with his melting ice cream cone patiently waiting there and softening in the warmth of the Anthropocene….Thanks for an informative piece and for the addendum which, as a Quaternary geologist myself, I really appreciated.

Question: Would Dr Thorson ever travel across CT to the Northwest Highlands of Litchfield County, and might he be available to present a keynote for a Land Trust’s annual meeting in February of 2020? There is a small honorarium and we can provide dinner with overnight lodging and maybe even a snowy walk across the Kame terraces, eskers, kettle depressions, and ground moraine that we have over this way.

Would love to have a contact for Dr. Thorson to explore the possibilities. Thanks, Starling Childs, MFS Norfolk CT

He can be found at the cryptic address robert.thorson@uconn.edu! Good luck with your keynote request; he’d be wonderful.

We used to slide down Horsebarn Hill on trays from the cafeteria. There were many romantic moments on the hill.

How do you make the correlation of husbandry with bigamy? My etymological research shows that the word husband comes from the old Norse which simply means keeper or tiller of the house.

It was our senior year January 1972 and my girlfriend and I had no plans on a quiet Saturday night. Snow had been falling since early evening and looking out the window of my Buckley Hall dorm room an idea flashed through my head. It was by then near midnight as I glanced to the corner where stood my 8’6″ Bing surfboard. Then I glanced to Janet with a mischievous smile. She read my mind before I said anything.

“You know what we need to do, right?” I said to her. I didn’t need say anything more.

“Let’s go!” she exclaimed as she put on her long coat and I grabbed the board and unscrewed the fin from the fin box. Down the elevator with the surfboard we went and out the doors and down the road we walked. Snow continued falling as she held tightly to my arm, giggling like a child.

We soon reached Horsebarn Hill. I placed board on the snow and Janet took the front position. I held her around the waist and gave a push. The incline of the slope was perfect for a good fast ride and reaching the bottom, we rolled off our make-shift toboggan into the snow laughing hysterically. We went back to the top of the hill for a second, third, fourth, and more rides until our legs were so tired we couldn’t continue. Of my experiences at UConn, it stands out as one of the most memorable and certainly the most romantic.

I enjoyed reading “The Shape of Storrs,” the development and history of UConn.I was born in the same year as UConn and experienced some of its growth. The last time I visited was 15 years ago and I hardly recognized the campus —buildings now stand where we had lawn and athletic fields. Thank you for your appreciation of the UConn heritage and the beauty that can still be found there.

Thank you for this informative view of the history of U-Conn. I graduated in 1966. When I attended the campus still had that warm small town feeling. At the time my home was in New London.

Now my wife and I live in Salida, Colorado. We truly love living here.

Thank you again for this really interesting piece of history.

Sincerely,

David

This was very interesting and enjoyable. I hope this does not mean that the print magazine is being discontinued. I prefer the printed addition.

Thank you.

Bob Skinner

Not at all, Bob. You should have received your print edition by now. Please let us know if you have not!

Lisa

Memories!

I did my BS and MS in Dairy Science at UConn. During my graduate student years we collected bulls 3 times a week right there in the paddock to the right of that barn. I went on to Rutgers for a Ph.D., doing research in Embryo Transfer, when it was just in its “infancy.†Although I yaught for 8 years at UGA, I went into business doing cattle reproduction for 25 years.

It all started at Horsebarn Hill.

Russ Page

I just loved this article. Prof. Robert Thorson reminded me that I enjoyed the ski slope on Horsebarn Hill when I was a graduate student in 1970. He also made me understand how the geology shaped the settlement of Storrs.

I also love the softly colored paintings by Blanche Serban which emphasize the gentle beauty of the hills.

Naomi Goring ’70 MA

Sneads Ferry, NC

Many thanks for bringing back fond memories of idling away warm afternoons on Horsebarn Hill when I should have been hitting the books! And not so fond memories of a year in The Jungle. We didn’t have motorcycles in the corridors, but the skateboards were sure fun.

Congrats to Blanch Serban on her beautiful painting!

Doug Larime ‘68 (SFA)

I love hearing your stories of Horsebarn Hill! Thank you also for the heart-warming words about my paintings.

Next time when you see me painting on HBH, please stop by to say hello. In the meantime, you could check other HBH paintings on my website at http://www.blancheserban.com , and a daily HBH painting posted on Instagram at Blanche Serban.

Blanche

Being the child of a UCONN Professor I spent many happy hours sledding on Horse barn hill in the 40’s and 50’s thanks for the memories.