tiny.

By Catherine Newman

Look: In one photograph, a crowd of museumgoers marvels at a trio of modern art masterpieces; in another, a swimmer strokes her way through a bubbly blue pool; in a third, a kerchiefed farmer tends her field of golden plants.

Look again: Those paintings are postage stamps; the pool is the inside of an ice cube; the field is the spiraling, floret- and filament-studded inflorescent center of a sunflower — who knew it was so elaborate?

The people are train-set miniatures, perfectly scaled to their Lilliputian landscapes — which is what creator Judy (Hall) Robinson-Cox ’71 (SFA) has titled this series. And even though she has assembled and photographed more than 100 of these wee scenes, the majesty of tininess continues to amaze her. “When you take a camera and really magnify something, it’s incredible what’s there,” she explains. “It really opens up a sense of awe — of what nature itself is, of the world we live in.”

At UConn, Robinson-Cox concentrated on photography and painting, which she studied with the late Anthony Terenzio. “He made me understand abstract art, which I didn’t know how to relate to at first. He opened my eyes.” Her own paintings and collages were primarily abstract still-lifes and landscapes, and her photography was largely experimental, shot with high-contrast film to reduce the images to a gray-free black and white.

She started graduate school here too, working with Clarence R. Calder Jr., an elementary educator and advocate for social justice who studied the impact of shop classes — what we might now call something like the pedagogy of engineering — and whose book of found-object projects she was illustrating. After a year, though, she describes being lured away by a “band of leather hippies.”

“These weird people had driven up in a bus to hold these leather workshops. And the belts they made were just like my abstract paintings! So I went to live with them in a big old house in Woodstock, New York — like a commune — where we worked for an advertising executive who had quit his job to start this leather craft business.” (“Wow!” I keep saying, and she laughs every time.) Eventually she returned to school, studying graphic design at Philadelphia College of Art, where she met her husband, Tom Robinson-Cox.

“When you look closely, the center of a sunflower is actually made up of tiny plants! And there are lots of similarities to the human body, cells, and the universe, the stars. It’s very intriguing . . .”

“When you look closely, the center of a sunflower is actually made up of tiny plants! And there are lots of similarities to the human body, cells, and the universe, the stars. It’s very intriguing . . .”

The two started working as fine-art photographers and moved to Gloucester, Massachusetts, where they now live and work, creating art of all sizes, which they show and sell at local galleries. Judy’s work includes seaside images of watery reflections, a series of conceptual pieces called “Mindscapes,” and evocative New England collages, among others. But it’s the diminutive series that seems to bring her (and her fans) the most pleasure, and she’s taken to selling the dioramas themselves, in addition to the images of them.

All that small-scale work started with a tiny plastic pig named Percy, whom Robinson-Cox had situated on a bunch of asparagus in order to liven up an image she was creating. Then Percy ended up on a head of broccoli, inside a pepper, and in a cluster of photographs, about which a curator in Boston said, “Why don’t you go all the way with this? Find some little people.” And so she did. (This story is told at greater length with delightful photographs in her Percy book, “Finding Lilliput.”)

“I’m attracted to small things,” Robinson-Cox says. “And I think I’ve never really grown up.” As a child with three brothers, she says she didn’t play with dollhouses but had lots of experience creating little villages for everybody’s train sets. She now has, by her estimation, around 1,000 of the ¾-inch figures. Her work is inspired by the figures themselves, as well as by whatever theme she’s working with in the moment. These have included fruits, vegetables, flowers, books, postage stamps, and sushi, among others.

“I started freezing the little people inside ice cubes . . . I had a little egg beater and I was furiously churning up the bubbles in my sink . . . I had to work quickly.”

“I started freezing the little people inside ice cubes . . . I had a little egg beater and I was furiously churning up the bubbles in my sink . . . I had to work quickly.”

“Every year I get interested in something,” she explains. “One year it was ice. I started freezing the little people inside ice cubes. And bubbles! I had a little egg beater and I was furiously churning up the bubbles in my sink, putting them around these tiny penguins. I had to work quickly.”

Other scenes require different feats of technological imagination: For a climber in a cavern, “I cut a bell pepper in half, then cut the back off of it. I put a tiny flashlight in the back so it looks like it’s glowing.”

A favorite of hers — a trompe l’oeil beach scene — was created with cornmeal, dried beans, and bulgur wheat, with a puddle of olive oil for the water. An image called “Cabbage Sea” was inspired by the wavy ruffled leaves of a savoy cabbage: “It just looked like water. Then I had to figure out how to make boats.” (Pea pods, naturally.) “My goal in making the pictures is to make people feel good,” she says. “That’s really as complicated as it gets.”

“But what’s the pleasure of tiny for the viewer?” I ask her. I’ve read articles suggesting that it’s a way for us to experience mastery over a miniature environment or that our love of cuteness evolved from the caretaking of babies. Neither of these quite captures the delight of Robinson-Cox’s work — of tininess expanding to fill the frame.

She’s not totally sure either, though she jokes it might be because she’s 4-foot-11 herself. But really she thinks it has to do with the scale-shifting that comes with macro photography.

“When you look closely, the center of a sunflower is actually made up of tiny plants! And there are lots of similarities to the human body, cells, and the universe, the stars. It’s very intriguing, a mystery.” A mystery, yes. And maybe something a little bit like magic.

“I cut a bell pepper in half, then cut the back off of it. I put a tiny flashlight in the back so it looks like it’s glowing.”

“I cut a bell pepper in half, then cut the back off of it. I put a tiny flashlight in the back so it looks like it’s glowing.”

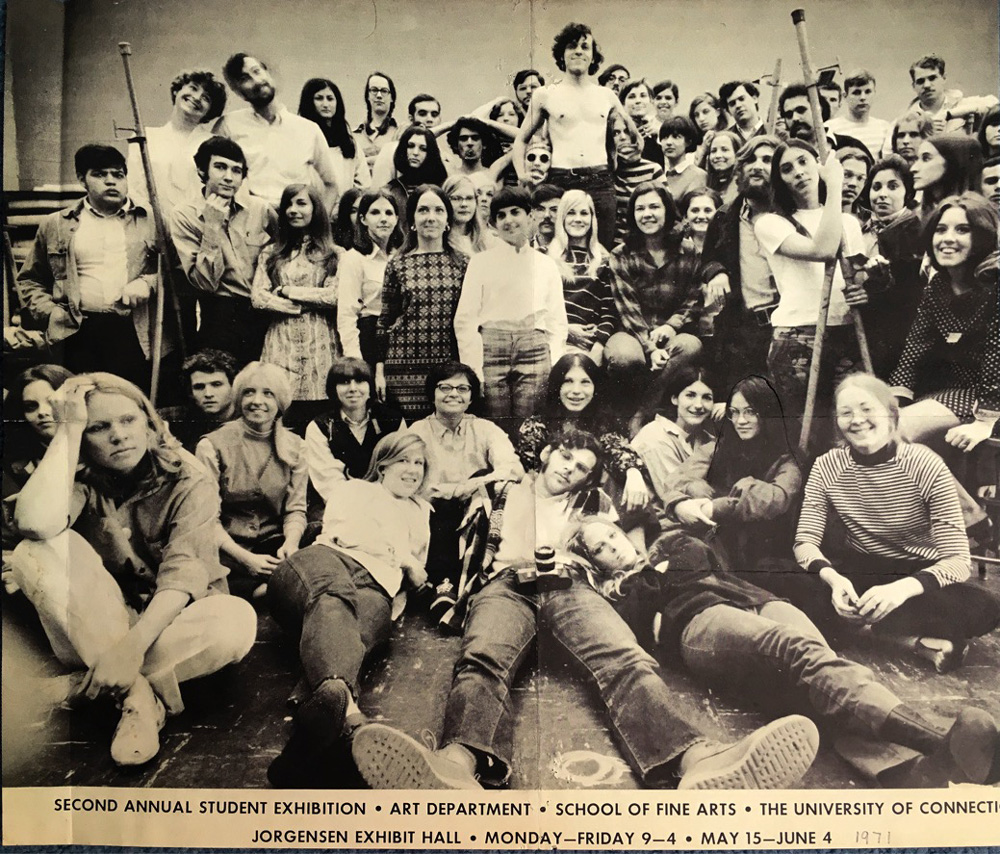

Judy, second from right on the bottom row of girls with a slightly visible pen outline around her head.

Leave a Reply