The Art of the Label

Behind every box and can in your grocery store is a UConn nutrition and arts degree

Illustration by Kyle Hilton

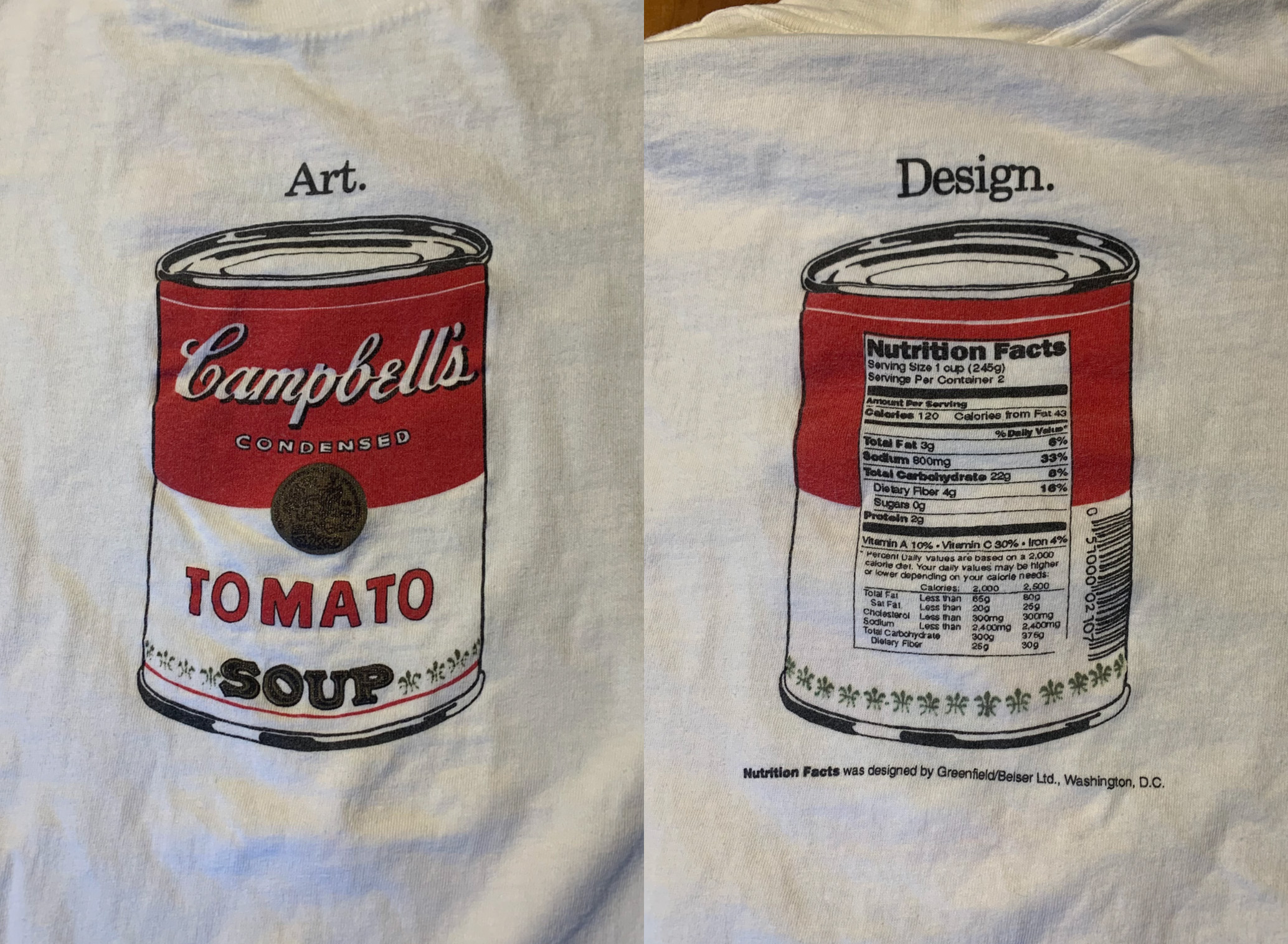

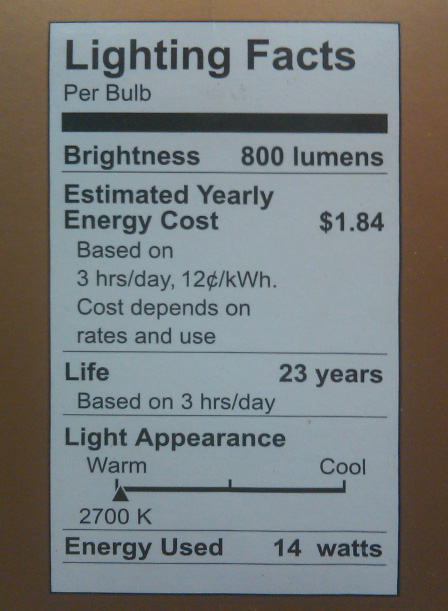

Andy Warhol, the Pop artist who turned soup can labels into art, might have admired the work of Jerry Mande ’78 (CAHNR). As an FDA policy analyst in the early 1990s, Mande, who majored in nutritional sciences and minored in art, played a key role creating the uber-ubiquitous “Nutrition Facts” label.

His interest in health began as a junior in 1976. He was puzzled why the FDA, fearing a cancer-causing food dye, had banned red M&Ms. “I took a nutrition class to learn more about it, and it snowballed from there,” says the Westport native, who is now CEO of Nourish Science, a Bethesda, Maryland, nonprofit that works to solve the nutrition crisis.

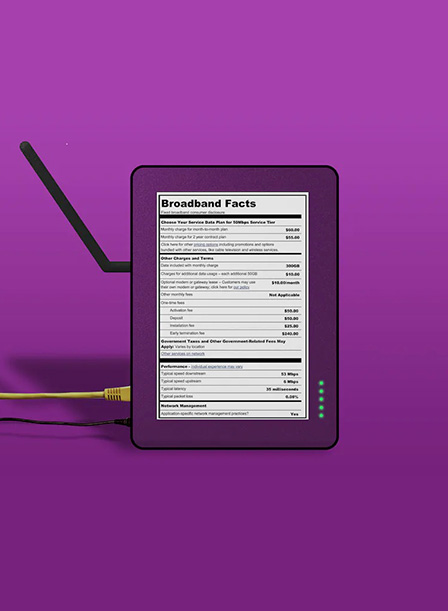

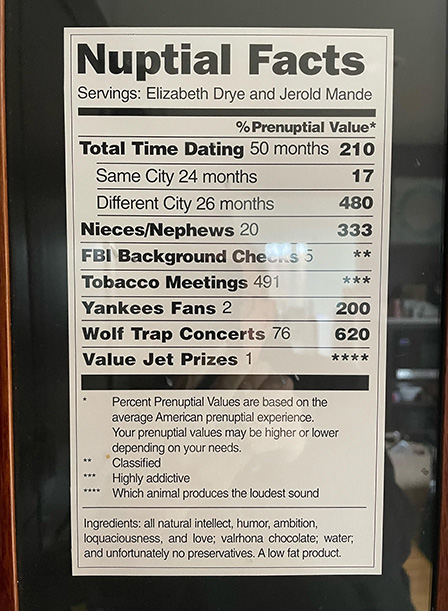

Mande was a legislative aide to Sen. Al Gore in 1990 when Congress passed the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act giving the FDA a comprehensive strategy on food labeling. Now all foods, with few exceptions, would carry a standard ingredients label to fight diet-related woes. While in Gore’s office, Mande had helped the then-congressman enact the National Organ Transplant Act, which created a national system to fairly allocate donated organs. But it was Mande’s interest in graphic design that caught the attention of former FDA commissioner David Kessler, who brought him on board. “Had it not been for Jerry’s efforts, we would not have the current food label,” says Kessler. “He was an intellectual giant, a visionary about how the label should look.”

In his book “A Question of Intent,” Kessler writes “Jerry took on the food label format as his personal mission, displaying a dogged focus that sometimes infuriated his colleagues. ...He was convinced existing information was being ignored by consumers for two reasons: it was confusing and hard to read, [and] Jerry reasoned we should make sure it could be read.”

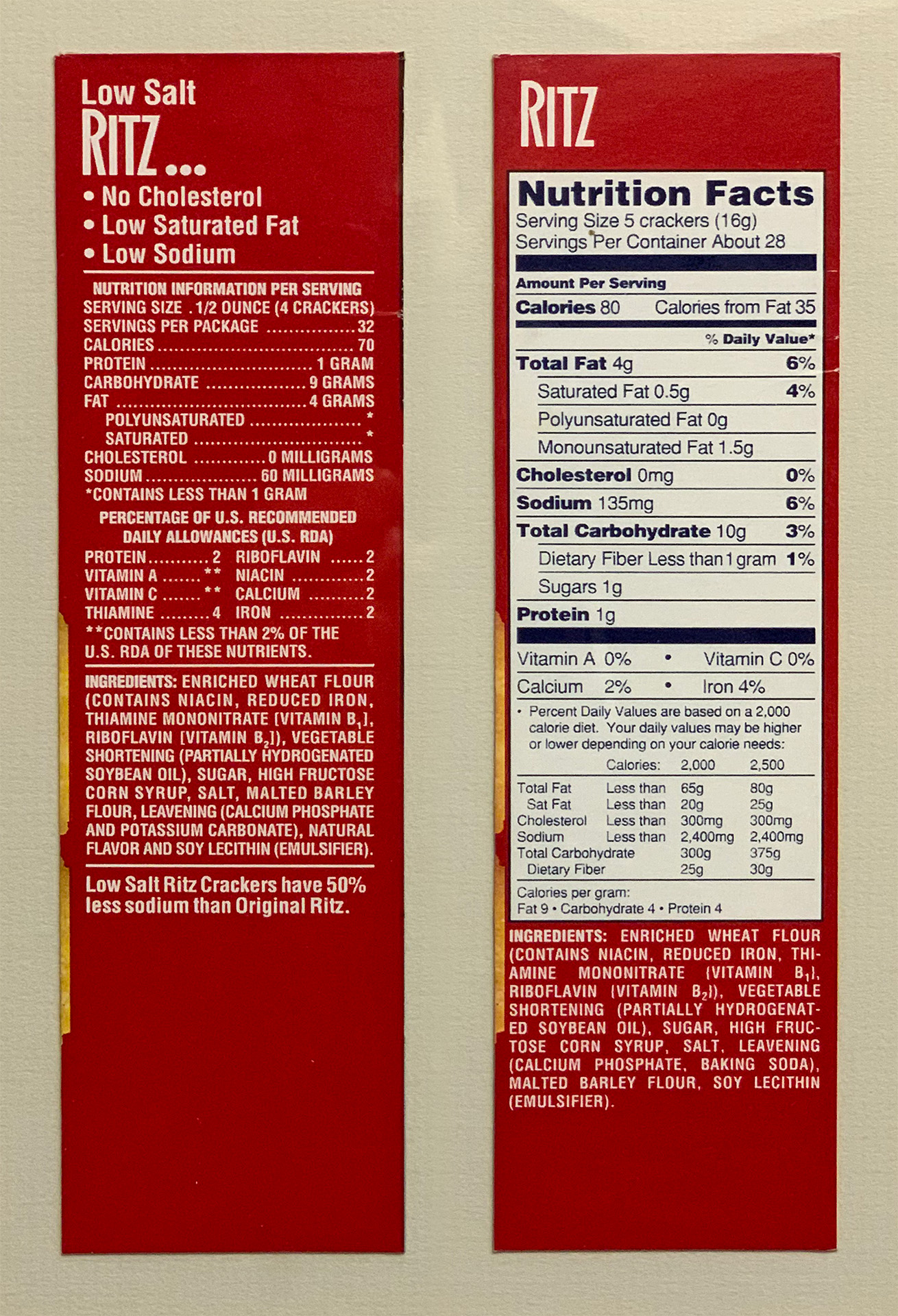

Working with the in-house art team, staffers, and social science experts who ran focus groups, Mande oversaw creation of versions of a possible label. But something was missing — pizzazz. Outside help came from designer Berkey Belser. He had created the yellow and black Energy Guide stickers for appliances in 1978 and agreed to work pro bono on the job.

Soon bold face type highlighted key terms. Tooling lines of different thicknesses separated items, making them easier to focus on. Words were justified and ran with the label’s margins to create more order. All punctuation was deleted, simplifying the look. Mande estimates the FDA considered three dozen preliminary versions.

He learned to be wary of focus groups. Consumers loved “prettier” designs with charts and graphs but disliked the stark version the FDA favored. “The problem was consumers liked more graphic versions, but had less understanding of what they communicated,” says Mande. “We faced this choice — do you go with one consumers like, or do you go with one they can best use?”

Opposition arose from the Agriculture Department, which had a competing label. President George H.W. Bush picked the final design, becoming the first occupant of the Oval Office to personally intervene in an FDA policy matter since Theodore Roosevelt in 1908 overturned a ban on saccharine.

From the moment the label hit grocery stores in 1994, it became an icon. “There is a masterpiece of information architecture printed on every food package sold in the United States,” wrote Italian designer Massimo Vignelli in AIGA, the journal of the Professional Association for Design. He hailed it as “a clean testimonial of civilization, a statement of social responsibility, and a masterpiece of graphic design.”

The National Endowment for the Arts honored the label in 1995, the same year it received a Presidential Design Award along with honorees that included the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

“In the end, its success is due to its simplicity,” says Mande.

By George Spencer

I think of you every time I see one of these!

As a trademark attorney, I found this bit of labeling history illuminating!