Farms = Food = Life

When alum Steven Were Omamo sees someone planting, he sees hope. The Nobel Peace Prize Committee seems to agree.

By Kevin Markey

Photos from WFP Media

"S

urprised, thrilled, humbled. All of those things," says Steven Were Omamo '88 MS of his reaction when the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize last fall. An agricultural economist with a master's degree from the College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources, Omamo is WFP's Country Director in Ethiopia. He leads a team of 850 relief and development workers, spread across 15 offices, who help feed some 8 million people a year.

"Surprised, thrilled, humbled. All of those things," says Steven Were Omamo '88 MS of his reaction when the United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize last fall. An agricultural economist with a master's degree from the College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources, Omamo is WFP's Country Director in Ethiopia. He leads a team of 850 relief and development workers, spread across 15 offices, who help feed some 8 million people a year.

"We're a big organization, but not as well-known as some," he says of the WFP, which is the food assistance branch of the U.N. "In many countries where we work, there are political sensitivities. We don't want to create hurdles for our delivery of food, so we tend to speak quietly. For the organization to be recognized was extraordinary."

If other agencies have higher profiles, few can match WFP's impact. It is the world's largest humanitarian organization, annually delivering some 3 million tons of food and over $2 billion worth of cash to well over 100 million people in 90 countries. Every day it sends thousands of trucks, ships, and planes into some of the most challenging places on Earth, many of them devastated by conflicts whose combatants use hunger as a weapon.

In bestowing the Peace Prize, the Nobel committee drew explicit attention to the link between war and hunger, highlighting how one contributes to the other in a vicious cycle: strife disrupts food security, while scarcity can trigger conflict that flares into violence.

"We will never achieve the goal of zero hunger unless we also put an end to war," the Norwegian committee noted in its prize announcement. "The World Food Programme has taken the lead in combining humanitarian work with peace efforts through pioneering projects in South America, Africa, and Asia."

Armed conflict is just one of several overlapping crises Omamo contends with in Ethiopia, where WFP partners with the government and other actors to keep millions of people from starvation. Recently one of his supply convoys disappeared while attempting to deliver humanitarian aid in the Tigray region, a mountainous area in the north of the country where the federal army and its allies have been battling rebel forces since November. The United Nations estimates the conflict has displaced more than a million people.

"There were three trucks," Omamo says. "They sent an SOS signal and for two hours, we couldn't contact them. Finally, we managed to raise them. They had been caught in a battle. They were not targets, but everything was unfolding in front of them." The relief workers escaped, and the mission would proceed another day. But the underlying conditions that drive hunger in many parts of Ethiopia — and around the globe — remain in place. In addition to war, Omamo says, these include climate shocks, gender inequity, chronic poverty, lack of local control of natural resources such as water, and now, economic deterioration due to the pandemic. "I really believe that Ethiopia is at the center of the world," he says, "in the sense that every issue you find around the world — both positive and less than positive — is expressed here at scale."

Kenya

A native of Kenya, Omamo grew up in the capital, Nairobi, spending school holidays on a farm his parents acquired when he was young. "The countryside has always been part of my world," he says. "Even today, my home in Kenya is in a rural area, and that is a comfort to me."

On the farm his family grew sugarcane and maize and raised cattle and other livestock. From an early age, he recognized farming to be a source of both income and deep emotional satisfaction. "I remember driving up to the farmhouse, usually arriving late at night from the city, and feeling my parents' pride in the place. It was fantastic. They were very devoted to the farm, very hard working. They ran it as a serious business enterprise, and it funded everything the family was trying to do, including university for the children."

For Omamo college meant California State University at Fresno, which his father recommended for its strong agriculture program, followed by UConn, then Stanford, where he earned his Ph.D. in agricultural economics. While at Fresno, Omamo says, he ventured off and tried many different things. Then one day he got a message from his mother: "Okay, now is the time to get serious. Back to agriculture." He went on to major in agribusiness.

He ended up at UConn in part because of a chance meeting in Kenya between his father and a visiting American political scientist, Fred Burke. A consultant to the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, Burke also happened to be vice president for graduate education and research at UConn. Always on the lookout for talented students to bring to Storrs, he immediately put the press on Omamo. "He was a very kind person, very generous. We became quite good friends," Omamo remembers. "He owned an island with some friends in upstate New York, and he took me there once. It was just fantastic."

Connecticut

Arriving in Connecticut in August, Omamo remembers being alarmed by the density of the foliage. "The trees seemed so close as we drove from the airport to Storrs. I was used to being able to see long distances. Where am I, I wondered? What have I gotten myself into? It turned out to be the start of a very rich, very special time in my life."

He moved into a graduate dorm (with a welcome view of an open field), joined the rugby club team as a player- coach, and formed many lasting friendships. "It was a very close community," he says. "Just a really great time."

Decades later, he easily recalls professors who influenced his career, including Boris Bravo-Ureta and Ron Cotterill from the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics. "That agricultural development is a quantitative study, I think Dr. Bravo-Ureta really put that idea in my mind," Omamo says. "Then Ron Cotterill was very much a principled antitrust guy. He was a believer in markets, but he also understood that they don't work well for everyone. These ideas ended up being quite important to me going forward."

One other idea that stayed with him — the importance of layering to survive a New England winter. "Somebody told me, if you do it right, you'll feel warmer than you did in the summer," Omamo recalls.

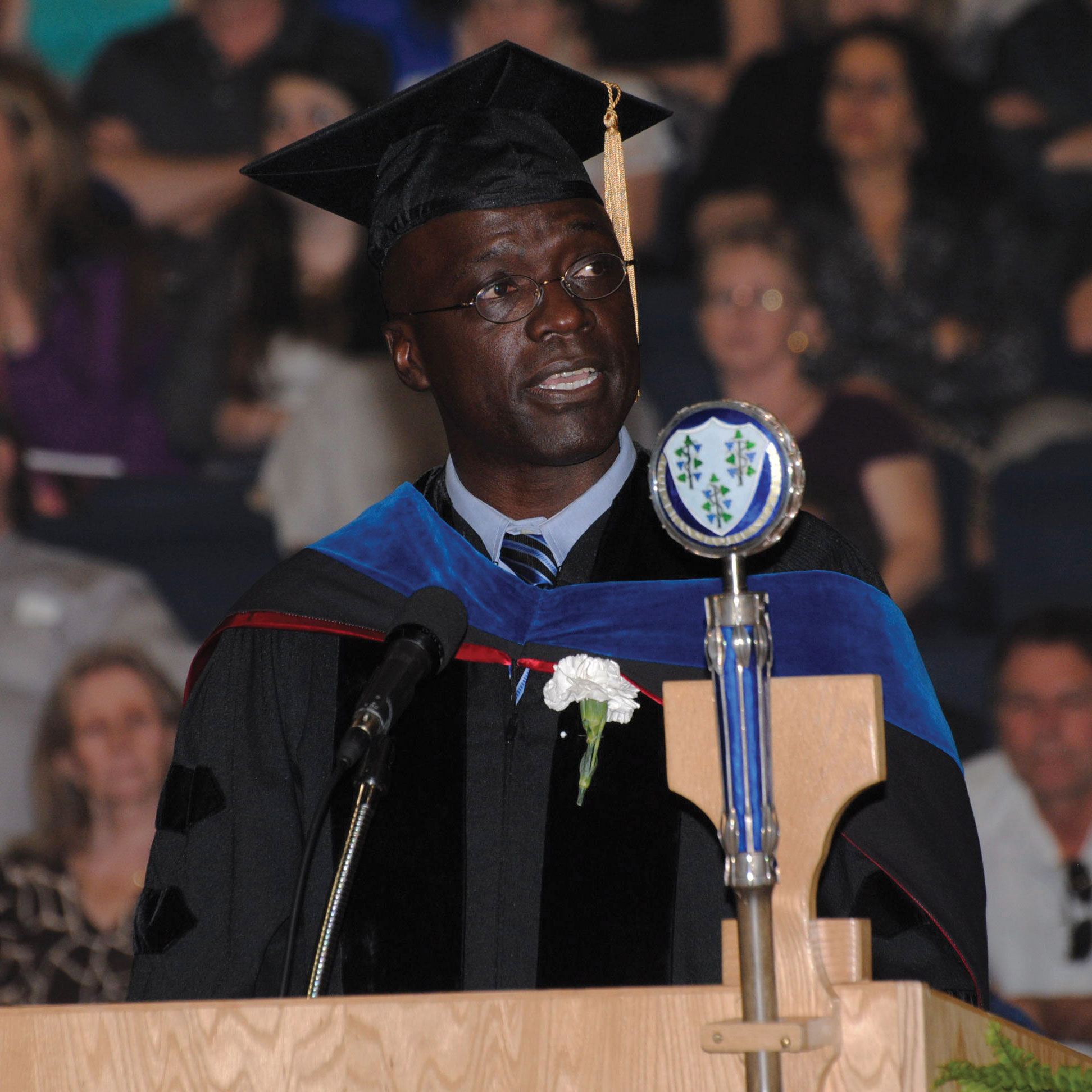

In 2014 Omamo returned to Storrs to deliver the commencement address to the School of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources. Bravo-Ureta was on hand to watch his former student congratulate graduates for choosing what he called one of the world's truly global professions. "And so anywhere you go," he told the class, "you will find people with a great deal in common with you, even if their lives look nothing like yours. And so as you build your careers in agriculture, as you address the many local and global phenomena that are rooted in or expressed through agriculture, I hope you find opportunities to embrace the huge diversity of people in our field, I hope you share your dreams with them, and let them enrich your lives and expand your horizons with theirs."

"It's easy to become dejected. But the transformation is happening."

Hover for More Info

Ethiopia

Omamo's own career has taken him all over the world. He has served as director of global engagement and research with the United Nations International Fund for Agricultural Development, senior research fellow and coordinator of the Eastern Africa Food Policy Network with the International Food Policy Research Institute, and director of policy and advocacy with the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa. From 2006 to 2012, he was deputy director of policy, planning, and strategy at the World Food Programme's headquarters in Rome. There he helped create and launch the Purchase for Progress initiative, a program that leveraged the enormous buying power of the WFP to support economic resilience in rural communities.

"The idea was that since we buy so much food around the world, we could target smallholder farmers with our purchases and so create sustainable markets for their produce," explains Omamo. Implemented in 2008, the program has become an operational model for WFP. It now is embedded in three dozen countries, connecting more than a million smallholders to valuable markets.

Wherever his work has brought him, Omamo has continued to feel the strong pull of Africa. "I really do relate to issues facing Africa and Africans," he says. "I've always been drawn back for that reason."

In Ethiopia those issues include recurrent drought, chronic undernutrition, limited access to health services and education, as well as the armed conflict emphasized by the Nobel Peace Prize committee. Additionally, the country shelters one of the largest refugee populations on the continent — some 750,000 men, women, and children displaced by political and climate shocks in neighboring Eritrea, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan. Together the crises threaten to upend a two-decade period of steady economic development that began after the end of the Ethiopian-Eritrean War in 2000.

To meet the challenges, Omamo directs a two-pronged response the WFP calls "saving lives and changing lives." The first part is crisis mediation, the work of distributing food to communities pushed to the brink of starvation by natural and manmade disasters. This involves everything from running school feeding operations to providing logistical support for Ethiopian government relief efforts to building humanitarian cargo hubs and even Covid field hospitals. The second pillar, the transformational part, addresses the root causes of hunger by supporting economic development, farming, and sustainable growth.

"What we try to do is give vulnerable communities opportunities to enter into the transformation," Omamo says. "Helping them manage natural resources, giving them access to markets, giving them new platforms, sharing new information or new financial instruments."

Despite the many complex issues, Omamo believes there is cause for optimism. He describes meeting an old man while in Kenya a number of years ago and asking him about his life. The man marveled at how easy in his lifetime it had become to move around. When he was young, he told Omamo, he couldn't go anywhere because his village was always fighting the village next door.

"It's easy to become dejected," Omamo says. "But the transformation is happening. Opportunities are always coming, in agriculture, in technology, in the penetration of markets. It's profound. Even in the most devastated community, you go there and you find people who are planting. They're looking ahead, trying to start again.

It is humbling."

"Plant something to harvest every year."

Hover for More Info

This is a great story about a great person and very timely. Keep the good work coming. Best

Proud to be a colleague of an inspiring and looking forward professional such as Omamo! Congratulations !