The Isis Terminator

On September 10, 2001, Brett McGurk '96 (CLAS) was a handsome, well-connected young lawyer whose life seemed to be unfolding in a straight line. Five years earlier, he'd graduated from UConn with a BA in political science. He'd gone on to law school at Columbia University, where he had distinguished himself editing the Law Review and winning an award for the best written brief in the school's Moot Court Honors Competition (his father was an English professor, after all). Young McGurk had every reason to think he was destined for a successful life in the law. And then everything changed.

By Peter Nelson

McGurk (right in both photos) with George W. Bush 2008 and Barack Obama 2016. (Official White House Photos)

T

he next day, on a crisp, clear morning under bright blue skies, two airplanes hijacked by a strange new group calling itself "Al Qaeda" crashed into the World Trade Center.

The next day, on a crisp, clear morning under bright blue skies, two airplanes hijacked by a strange new group calling itself "Al Qaeda" crashed into the World Trade Center.

"I'd been fortunate enough to get clerkships on the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in Manhattan and then on the U.S. Supreme Court. I was at the Supreme Court on 9/11 with Chief Justice Rehnquist. He told me a plane had just hit one of the Twin Towers. We thought, like everybody at the time did, that it was a tragic accident. There was no internet at the Supreme Court in those days. Justice Souter's chambers were right next to my office, and his secretary came in looking anguished. They had a little black and white television, so that's where I saw the towers fall. I went back into the chambers with Rehnquist, and the marshals were in there by that point encouraging him to leave. He didn't want to leave because we had a lot of work to do that day, but eventually they ordered all of us out. We were told, as we were leaving the building, that a plane was coming to the Capitol, which was right across the street."

American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon, killing 125 people. McGurk, a mere three miles to the east, had more reason than most of us to think, That could have been me. Another plane, United 93, thought to be headed for the Capitol, crashed in Pennsylvania, brought down by ordinary citizens who stormed the cockpit once it was clear what was happening.

Like so many Americans that day, McGurk felt called to action, felt a need to do something about it, but so many questions had to be answered first. Who and where was the enemy? What did they want? And later: How do we fight them effectively? McGurk didn't realize then that he would spend the next 17 years trying to answer those questions, eventually becoming arguably the foremost expert on the subject and the man who would help formulate and execute the plan to defeat the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, aka ISIS.

He knew then, however, that military service was out. A high school injury had left him with plates and screws in his leg that foiled his hopes to play hockey at UConn and then caused him to leave the University's Army ROTC program too. But his work in the field of constitutional law as a clerk at the Supreme Court led to an invitation to join the American team in Baghdad shortly after the invasion of Iraq.

"I went to Iraq in January 2004. I spent a year on the ground there. I saw the whole thing, up close, in Baghdad, the constitutional process of forming a new government, setting up a U. S. embassy, and working with Coalition Provisional Authority, led by Paul Bremer, until it dissolved. I saw, up close, the gap between our objectives and our resource base, what I call the gap between our ends and means. We were orders of magnitude off the target in terms of the resources required to achieve what our country had set out to do in a country we barely understood."

The objective was to build a democracy to replace the strongman dictatorship that had ruled Iraq for 35 years, while sorting out who we could work with and who we couldn't. It meant identifying, locating, capturing, or eliminating the enemy, the Ba-ath Party members on the famous deck of cards, including Saddam Hussein at the top of the deck, but it also meant building hospitals and schools and replacing the infrastructure damaged during the war. It meant being able to make promises and keep them. It meant understanding all the different sources of conflict in the Middle East (see below) and finding common ground. Finally, it meant putting in place suitable leadership. For McGurk, it was the application of political science at the most basic level.

"The intellectual rigor at UConn . . . prepared me for everything from the Supreme Court to the White House to building up one of the largest coalitions in the world and working with three very different presidents."

"I was in the honors program in political science at UConn, reading multiple books a week and writing all the time, and taking graduate level courses," McGurk recalls. "I had a professor named Bob Gilmour, who was very demanding, but he also encouraged me to set my sights high. He pushed me quite a bit. The intellectual rigor at UConn, in the political science program, really prepared me for everything from the Supreme Court to the White House to building up one of the largest coalitions in the world and working with three very different presidents."

McGurk went to the White House in 2005 to serve President Bush for his second term. "I was with him when we did the surge. Finally, in 2006, we dramatically changed the strategy, which was long overdue, and sent 30,000 troops to Iraq. We reversed what had been an underlying assumption, believing political progress would lead to security; in fact, security was the precondition to everything else — and that required more resources and personnel. I worked closely with President Bush through that decision and its execution. It was a difficult period."

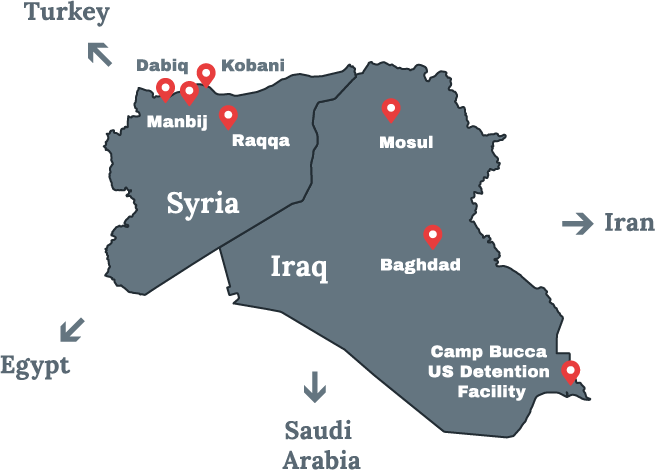

2006 was also the year ISIS began to coalesce. It began as a notion that a Sunni homeland was possible, as conceived by a group of prisoners at the Camp Bucca U.S. detention facility in southern Iraq. The camp held 20,000 Iraqi prisoners, including former Ba-ath Party members and Sunni ex-military officers under Saddam. That population also included a man named Awwad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri al-Sammarai, a preacher from Douala province, born in Samarra in 1971, with degrees in Islamic studies from the University of Baghdad. When the Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the head of AQI (Al-Qaeda in Iraq), was killed by drone strike in 2006, al-Sammarai changed his name to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and declared himself caliph, the messianic head of a new group calling itself ISIS.

"Radical groups fill vacuums," McGurk observes. "We may want to believe or hope the collapse of state authority will be replaced by moderates, but in fact, as we've seen from Iraq to Libya to Syria, collapse of state structures creates conditions for extremist groups to thrive. ISIS had a very clear plan, to use ruthless violence to carve out its own state from chaos. It took advantage of Iraq and later the civil war in Syria to do just that."

Counterterror

Where some make meaningful distinctions between Al Qaeda and ISIS, McGurk sees it as a continuum and a difference of degree.

"It's a pretty symbiotic relationship," he says. "They had some disagreements. Whether to form a caliphate, or government under this Messianic leader, was one. And who could be targeted for death. ISIS takes a much more expansive view of that, of who is an infidel, than Al Qaeda would. But in terms of threats to us and our partners around the world, it's not that different." McGurk was one of the first officials to raise the alarm, testifying in the fall of 2013 about the rising threat, which was then still known as al Qaeda in Iraq and Syria.

ISIS gained international attention in 2014 with videos showing prisoners being beheaded, including American journalists James Foley and Daniel Pearl. The videos were for shock value, to get attention. But, says McGurk, ISIS grew its ranks mostly with propaganda that pushed a positive message.

"They said they were creating an Islamic homeland which would be paradise on earth, run the way the prophet Muhammad said it should be run. They had a very deformed interpretation of Islam, but it found a broad appeal. Their message was, 'We're creating an Islamic homeland, as it was supposed to be created, a true caliphate.' And every Muslim around the world had a duty to come and live in the caliphate. And they wanted to expand. Their bumper sticker was, 'Remain and Expand.' And it attracted people from all around the world. Forty-thousand people poured into Syria to join these extremist groups."

ISIS promised power to the powerless, a voice to the voiceless, honor and dignity to victims of an Arab diaspora that had left people feeling alienated and persecuted and disenfranchised. A new golden age.

"And from [the caliphate]," McGurk says, "they had a sanctuary to plan and plot and implement major terrorist attacks." McGurk cites the attacks in Paris, where bombs at a soccer game, at the airport, and at a heavy metal concert killed 130 and injured over 400 in November of 2015. "That was planned in Syria. The people who set off suicide bombs at the airport in Brussels trained in Syria. There were a number of attacks in Turkey. They were busy trying to inspire people to commit other terrorist attacks."

McGurk meeting with the Raqqa Civil Council Aug. 2017 (Delil Souleiman/AFP via Getty Images)

ISIS also spouted an extreme theology that was explicitly eschatological, an end-times strategy where the more enemies they made, the better. The violence depicted in the videos was, in part, intended to bait the United States into a direct confrontation that would bring about armageddon in a place called Dabiq. They hoped it would spur the return of the Mahdi, the last of twelve sacred Imams, who would emerge from 1,400 years of occultation to defeat Satan and rule over Earth with Islam as the single unifying world religion.

The Western powers declined to take the bait, but the brutal imagery was nevertheless effective in that it scared and intimidated anybody who found themselves in the path of ISIS fighters — including tens of thousands of Iraqi soldiers in Mosul who, confronted by ISIS combatants in June of 2014, took off their uniforms, laid down their weapons, and disappeared. ISIS fighters saw victory after victory during a remarkably effective campaign in the summer of 2014 that eventually seized an area the size of Great Britain and controlled 8 million people. This was a thugocracy fueled with revenues from extortion, kidnapping, and stolen oil exceeding a billion dollars a year. They might indeed have been able to "remain and expand" were it not for a coalition McGurk helped put together and sustain. By 2014, of course, U.S. presidents had changed, but McGurk remained.

Coalition Building

"I was in Iraq when Mosul fell," McGurk recalls, "and I was working very closely with President Obama, and the chairman of the joint chiefs, with our generals and Vice President Biden and John Kerry, when we developed a campaign to push back. The plan was to have a very large international coalition for burden sharing. We had to get the regional countries involved. We were not going to put U.S. combat brigades in place to do the direct fighting."

ISIS suffered its first defeat in August of 2014 in a town called Kobani, on the Turkish border. ISIS was about to overrun it when the United States entered the battle, providing radar-equipped air support and a small number of Special Forces advisors on the ground.

"There were Kurdish fighters in the town, who were surrounded. It was through our relationships, and working in Iraq for so long, that we were able to get in contact with those fighters in Kobani." The Kurds were led by General Mazloum Kobani Abdi, whom the New Yorker dubbed "The General Who Defeated ISIS." General Kobani headed the Syrian Democratic Forces, but, says McGurk, he could not have done it without coalition support.

"I went to Turkey to negotiate with the Turks and the Iraqi Kurds to get the Peshmerga, the Kurdish fighters, into the town. That was the turning point. The battle went on for about four to five months, but that was the first real significant battle that ISIS lost. They lost about 6,000 fighters in that battle. That gave us a foothold in Syria. We then were able to build from there and gradually start to claw back territory. The campaign plan was very carefully drawn, but the real credit goes to the Iraqis and the Syrians who did the fighting and took thousands of casualties. What we were able to do in northeast Syria, we did because we had U.S. people on the ground.

"We were able to build a force of 60,000 fighters, with Kurds and Arabs and Christians, very effectively. We coordinated with the different leaders, Arab sheiks or Peshmerga leaders, to build alliances. We recruited trainees. We set up training camps where our Special Forces trained thousands of recruits who would be put into the Syrian Democratic Forces fighting against ISIS. Our message to them was, 'You can go home again. We'll help you take back your home.' It was very effective."

McGurk made sure there were humanitarian resources available for the refugees liberated from ISIS-held towns and territories, including Mosul.

"The humanitarian experts at the time told me there hadn't been a refugee crisis like that since World War II," McGurk says. "Every I.D.P. (internally displaced person) who came out of Mosul during the battle to retake it received shelter, food, and basic necessities."

In the midst of leading the successful campaign to defeat ISIS, McGurk was asked by President Obama to lead other troubleshooting assignments across the Middle East, from negotiating with the Russians over Syria ("those are bare-knuckle talks," he says) to a secret channel with Iran to secure the release of seven Americans from Evin Prison ("probably the most the difficult thing I've done," he recalls).

Not only was McGurk one of the first to sound the alarm about ISIS, he also was one of the first to warn of the consequences if the U.S. reneged on its promise to support the Kurdish fighters who'd put themselves in harm's way. McGurk resigned his position on December 22, 2018, when the administration first announced its intention to draw down troops from Syria.

So what now? In the fight against ISIS, the killing of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is "great news for the civilized world." But, he cautions, "One hard lesson we learned over the years is you cannot just declare victory, pick up stakes, and leave. That's a huge mistake. We designed the campaign against ISIS to avoid over-investment, ensure that battlefield victories would be sustainable, and support diplomacy against other major powers in both Iraq and Syria. It was working fairly well until the decision was made nearly overnight to give nearly all the ground ISIS had lost over five difficult years."

In addition, as many as 18,000 ISIS fighters may be reorganizing in Syria while spreading their influence to Afghanistan and Africa. McGurk is worried that we could be making the same mistake all over again.

"At Camp Bucca, we learned a lesson. You can't just let these guys sit in a prison facility. Right now, there's a detention camp at a place called al-Hol, in northeast Syria, where there are 70,000 prisoners, including some pretty hardened ISIS fighters." With only 400 Kurdish guards, a September 3, 2019, New York Times article calls al-Hol a "disaster in the making." The Washington Post calls it a "cauldron of radicalization." Others call it an "ISIS academy."

"I don't want to wake up 10 years from now," McGurk says, "and read that somebody, some future Baghdadi, came out of al-Hol. It's a problem the United States can't deal with on its own. It's something that requires the attention of the whole international community."

Training a New Guard

As for McGurk himself, for starters he's taking his shade under the palm trees on the campus of Stanford University, where he is the Frank E. and Arthur W. Payne Distinguished Lecturer at Stanford's Freeman Spogli Institute. The Stanford campus, with its red brick buildings, Spanish tiled roofs, and green expanses, is far from the hue and cry of the Middle East, the bombed-out shells of wrecked buildings in Kobani or Raqqa, where McGurk worked to counter terrorism. But educating the leaders of tomorrow is important too, he says.

He teaches a master's program course called Presidential Decision Making in Wartime about wartime strategy from Truman all the way up to Trump. And he's writing a book about the last three presidencies, three approaches to war, and "how they navigated these difficult issues and what lessons to take from them in the future."

His coalition is still together; it was carried forward from Obama."I worked on that transition from Obama to Trump and served two years in the Trump administration," says McGurk. "I'm proud of that. Even with everything going on in Washington, we had a pretty smooth transition, which was important, because we were in the middle of a war. And it was a very hot war when Trump took over. We had a pretty good transition. I think it was very professionally done. And that's important."

McGurk speaks with humility about the experience over the last 15 years strewn between the Oval Office and the battlefields of the Middle East. "I'm hopeful our country can return to basic principles in foreign affairs, meaning alignment of ends and means and resisting the temptation to set objectives we are simply unable or unprepared to meet. We also need friends. ISIS is a global problem; that's why it took American leadership to build a global coalition to defeat it. We could not have done it ourselves."

It certainly could not have been done without McGurk.

Historical Causes of Conflict in the Middle East in 500 Words

THE ISLAMIC SCHISM

In the year 632 AD, the death of the prophet Muhammad was followed by a dispute as to who Muhammad's rightful successors were; Shia Muslims (about 10% of the current world population of 1.6 billion Muslims) believe the prophet named his cousin and son-in-law, Ali, while Sunnis believe Muhammad's father-in-law, Abu Bakr, was the proper leader of the faith, generating a permanent split between the two branches.

ARTIFICIAL BORDERS

The Ottoman Empire, est. 1299, brought order to greater Arabia (not including Persia); that stability collapsed after the Ottoman Empire was defeated in World War I. The Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 divided the conquered Ottoman Arab provinces into regions of British and French influence, creating artificial countries in the hope of unifying various ethnic/linguistic/sectarian groups that in turn rejected the illegitimate governments imposed on them.

OIL KINGDOMS

Eight years before Sykes-Picot, oil was discovered in the Middle East; the oil-dependent economies (and political interests) of the Middle East and the Western powers became forever entangled, major powers vying for dominance to secure the oil supply, leading to proxy wars and the arms shipments that make them possible, if not inevitable.

WAHHABISM

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, est. 1932, produced a paradigm shift when the House of Saud adopted Wahhabism as the state religion, based on the teachings of a Sunni cleric named Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703"“1792), who advocated a return to the original ultraconservative (and antimodernist) practices described in the Koran (Salafism/Sharia) that shunned outsiders, restricted women's rights, and punished as infidels or apostates (takfirism) anyone departing from Wahhabism.

SECULAR STRONGMEN

The declension of the British Empire in Arabia following World War II created a power vacuum filled by dictators, sheiks, and military leaders who established rule-or-be-killed despotic governments, led by men like Muammar Gaddafi in Libya, Saddam Hussein in Iraq, or Hafez al-Assad and his son Bashar in Syria.

RELIGIOUS STRONGMEN

The fall of the Shah of Iran in 1979, overthrown by forces loyal to the Ayatollah Khomeini, threatened secular governments with sectarian/theocratic opposition.

DEMOCRATIC POPULISM

Opposition by moderates (mobilized by social media) to oppressive regimes began in Tunisia in 2010 (the "Arab Spring") and spread to Libya, Yemen, Egypt, Syria, and elsewhere, formed by people who agree with Martin Luther King that the moral arc of the universe bends toward freedom.

TRIBALISM

Conflict at the most local level, smaller groups unified by ethnicity, kinship, language, custom, territory, or religious subdivisions, led by chieftains or warlords contending with each other because, for one hypothetical example, the leader of one village sent the leader of another a lousy wedding gift three hundred years ago.

CLIMATE CHANGE

A drought from 2006 to 2010 desertified 60% of Syria's arable land and drove 1.3 million internally displaced people from rural areas into the cities looking for work, food, and shelter, creating conditions ripe for political upheaval; climate-driven pressures are likely to worsen in Africa and the Sahel, in the Middle East, in Central America, and in territories rendered unlivable by rising temperatures.

Brett McGurk is a fool for believing that the U.S. militarism in the Middle East is in our national interest. Like the Johnson administration during the late 1960’s, he can’t see the forest for the trees. Like others who served the Bush administration, his hubris knows few bounds. When do these guys ever learn?

I just read this article about Brett McGurk (UConn Graduate) and his service to our country. He is truly an amazing man and our country is fortunate to have people like him serving.