Building Futures

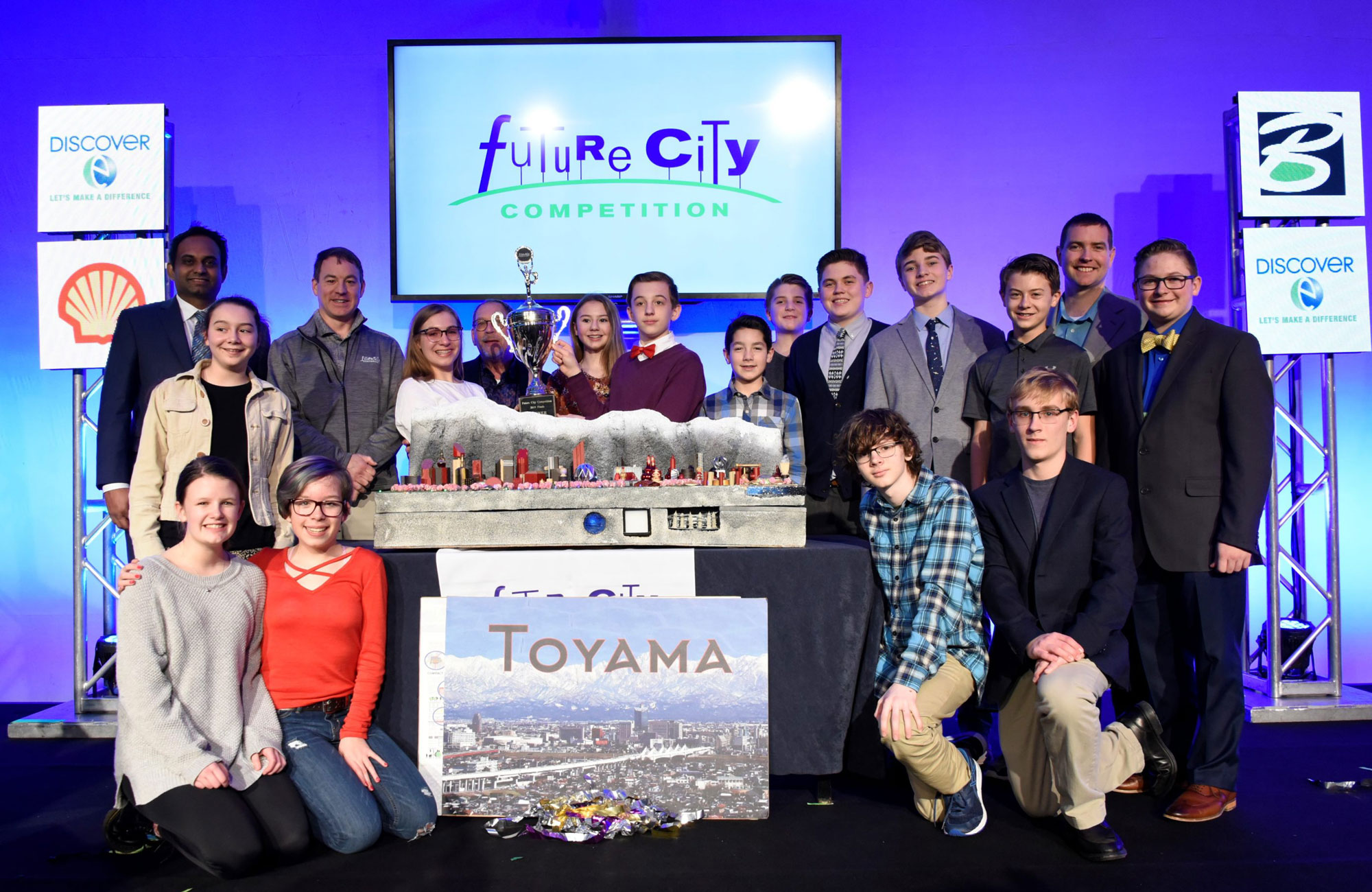

The Warwick Middle School team after winning the 2019 Future City competition in Washingon, D.C., with teacher Michael Smith '08 MS (back row, second from left).

At a small school in central Pennsylvania, Michael Smith '08 MS has built a national powerhouse. Eight regional titles in thirteen years. Six top-15 finishes in the national rankings. The 2019 national championship.

Football? Basketball?

Try engineering.

A gifted support teacher at Lancaster County's Warwick Middle School, Smith guides a crew of seventh and eighth graders in the annual international Future City competition, a project-based learning program that challenges students to conceive, research, design, and build scale models of sustainable communities. Storm-water management, urban agriculture, and green energy are among the issues middle school students have tackled during the 27-year history of the competition. For this year's timely theme, Powering our Future, kids had to come up with power grids capable of withstanding natural disasters.

Competition is fierce. Some 40,000 children representing 1,500 schools from around the United States, as well as teams from Canada and China, participate in Future City. Fewer than fifty schools make it all the way to the finals in Washington, D.C., each February. Science academies and STEM magnet schools are disproportionately represented.

"That's what we're up against," says Smith proudly. "I have a gifted population at my school. Their whole school is gifted. I'm just so proud of my kids and their achievement."

He attributes Warwick's remarkable success in part to the training he received at Neag School of Education, from which he holds a master's degree in gifted education. "I have never had an engineering class in my life," says Smith, who also holds a MA in history and began his career as a social studies teacher. "I learned how to think, how to compete, and how to win an engineering competition thanks to UConn."

Confratute

A formative part of his UConn experience, Smith says, was Confratute, the week-long conference hosted each summer by Neag's Renzulli Center for Giftedness, Creativity and Talent Development. Launched in 1977 by Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor Joseph Renzulli, a longtime education psychology professor, and Sally Reis, the Letitia Neag Morgan Chair in Educational Psychology and fellow Board of Trustees Distinguished Professor, Confratute brings together teachers to explore ways to make school more engaging for all types of students. Renzulli has said that he and Reis conceived Confratute as a sort of hybrid professional development event "“ "part conference, part institute with a great deal of fraternity in between." For attendees, the array of daily sessions "“ kinesthetic storytelling, forensic science techniques "“ add up to an intensely energizing experience.

"You're taking about people from all around the world showing up to share ideas," says Smith. "It's kind of hard to describe how good that is to be in the midst of that, all these excited, mostly gifted teachers working with people who are drivers in the field. It's the excitement of being with people who want to make a difference in kids' lives."

In his own classroom, Smith constantly looks for ways to make learning dynamic for his students. Early in the school year, for example, he has his seventh-graders deliver a presentation in the concise Japanese storytelling format known as Pecha Kucha, where speakers show 20 images and talk about each one for 20 seconds. By spring the kids advance to more wide-open projects. "I want them to move away from strictly informative presentations toward creative-productive projects," Smith explains. "We need creators and innovators, and I believe most students have largely untapped potential."

Another strategy he uses is to bring in guest speakers. These have included the inventor of an RFID chip who talked about the critical importance of developing good writing and speaking skills, because no matter how great your ideas may be, "they're no good to anyone if you can't communicate them;" a geologist who was part of the team that helped discover water on Mars; a county election commissioner who provided a ground-level look the mechanics of democracy; and an author who discussed the difference between "Outliners," writers who plot in advance every element of a story, and "Panthers," who just jump in and discover their voices as they go.

"My students operate that way," says Smith. "They're Panthers. Middle schoolers aren't known for planning. So it's awesome for them to hear something they can relate to, it carries great authenticity."

City Planning

Then there's Future City.

Smith introduced the program as an optional activity not long after starting at Warwick in 2006. He soon discovered that the cross-curricular nature of the competition — applied math and science, public speaking, project management, effective technical writing, and blue-sky idea generation all come into play as students design, build, and present their models — provides an ideal platform for collaboration.

"You need your artists, you need your electrical technicians, you need your computer programmers, you need your presenters who will explain the project to the judges," Smith says. "No one person can do this. Everyone has to draw on their creativity and critical thinking and problem"“solving abilities as they work together. It's like a perfect compendium of essential 21st century skills."

One of the challenges of teaching gifted children, Smith says, is finding ways to unlock their talents. It's not uncommon for high-achieving kids to get trapped by their own perfectionism. To counteract fear of failure, he works hard to create a friendly learning environment where kids feel comfortable trying new things.

"I give them permission to make mistakes," he says. "I tell them that things probably will not go right the first time or the second time or the third time for that matter, and that's o.k. It's amazing the power you give a kid when you say you believe in them, and then you give them responsibility for their work."

Competition

As it began the 2019 Future City campaign, the 25-member strong Warwick team set out to learn as much as it could about modern energy infrastructure. The students' research led them to the chief resiliency officer of Toyama, a flood-prone coastal city on Japan's main island of Honshu. During a Skype session with the class, he explained some of the things Toyama currently does to protect its power grid from natural disasters. The kids then imagined what sorts of carbon-neutral technologies the city might employ a hundred years from now.

"We would all sit down around a table and just throw out ideas and bounce things of each other," says Grace Kegel, a seventh-grader who was one of Warwick's three presenters in Washington. "I'd be lying if I said that these table talks didn't often end in small arguments that had to be settled."

Among the solutions the team came up with were solar roadways, hybrid hydro-electric-nuclear fusion power generation, and embedded power lines. They then built an elaborate 50-inch by 25-inch model to showcase their ideas.

Constructed over the course of hundreds of hours on mornings, afternoons and weekends throughout the fall, the final product was a thing of beauty. Along with lovingly detailed snowcapped mountains and flowering cherry trees, the students incorporated a magnetic transportation system and a sophisticated LED display that illustrated the complex power grid they'd designed. The piece de resistance was fast-flowing river whose floodwaters, discharged by a pump hidden the model's base, were diverted into underground collection tanks.

"We would talk about the design, draw it, and work on it, cutting, drilling, and soldering," says eighth-grader Xavier Flaiz. Part of the team responsible for designing the model's moving parts, he loved how the project rewarded creative problem-solving. "It was like a puzzle," he says, "but more hands-on and very fun."

Smith has seen plenty of models over the years, and he knew his team had outdone itself with Toyama. After breezing through the central Pennsylvania regional, Warwick arrived in Washington for the four-day national competition feeling hopeful. Still, Smith advised the crew to try to relax and not get ahead of themselves. Against a deep and talented field studded with five past winners, including the defending national champion, there could be no guarantees.

Which made it that much sweeter when Warwick was called on to the Hyatt Regency's grand stage to receive the victor's trophy.

"When we won it felt like proof that the future is going to be okay," says Grace. "We took a city and we made it better. We had the chance to design the city of our dreams, a place that everyone would love to live in and that could withstand all and any obstacles that it was faced with."

So, what's next for Warwick now that it's had some time to reflect on success? Where does the team go from here?

"The kids are so excited, they're already meeting on Sundays to plan for next year," Smith reports. "And we don't even know what the theme is yet!"

By KEVIN MARKEY

Photo courtesy of FUTURE CITY

Leave a Reply