The

Knock-out Doctor

}Ringside, cageside, in the bullpen, and on the field, neurologist Dr. Anthony Alessi is on a mission to save as many human brains as possible.

By Peter Nelson

Photos by Peter Morenus

W

What happens to Carrington Banks, 29, from Peoria, Illinois, just before 9:30 p.m. on the 12th of October in the Mohegan Sun Casino, with just under a minute to go in the second round of a mixed martial arts (MMA) fight, is either something he will never forget or something he won't remember — specifically a hard right knee to the chin, delivered by an opponent named Mandel Nallo, just as Banks is ducking his head to move in closer. The knee is the last thing Banks sees before it all goes dark.

The next thing he sees is the face of Dr. Anthony Alessi, UConn Health clinical professor of neurology and orthopedics and director of the UConn NeuroSport Program.

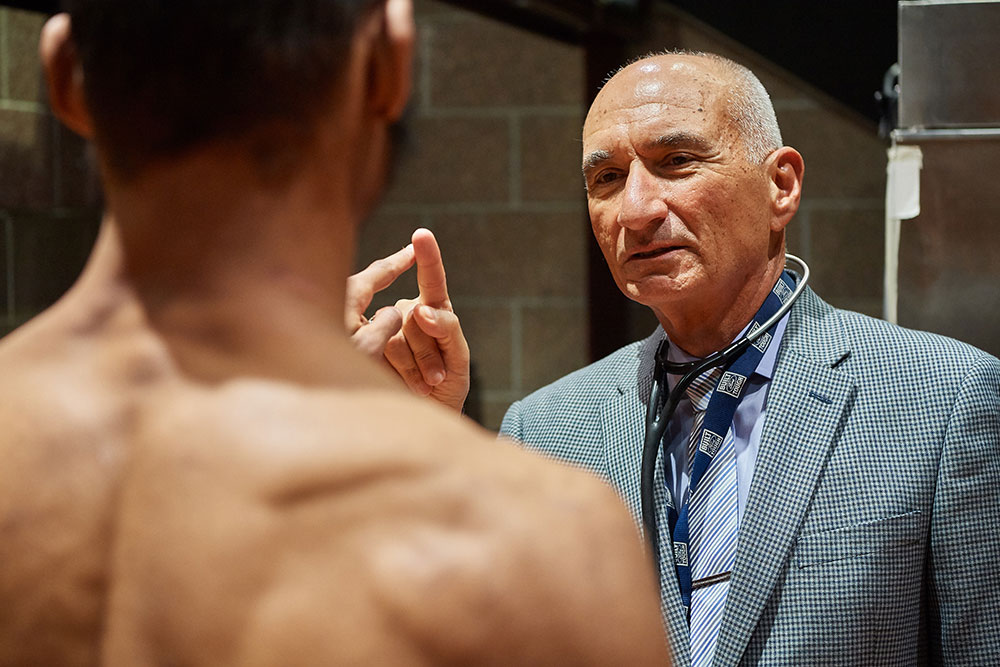

Alessi, an energetic man in a light grey suit and athletic shoes, shines a light in Banks's eyes to see if they dilate. The two are backstage beneath the arena, where Banks is seated on a chair sequestered by black partitions. Banks is confused and angry and wants to know why they stopped the fight, because he says he's fine and he wants to continue.

"You took a nap. You were out for a couple of minutes. Come on. You gotta go," Alessi tells him, gesturing to a ramp where the lights of a waiting ambulance flash. Banks walks to the ambulance under his own power with Alessi steadying his elbow to make sure he gets to the hospital for further examination.

"In pro football," Alessi says, "you get hit hard in the head, they take you out and put you into a concussion protocol. In boxing or MMA, if you took a guy out every time they got hit in the head, the sports wouldn't exist. My job is to make sure all these guys go home alive. That's why I'm here."

"In one of the night's main fight, Russian heavyweight Sergei Kharitonov deals Las Vegas native "Big Country" Roy Nelson an illegal knee to the face, which brings ringside physician Alessi into the cage; he and the ref have five minutes to decide whether the fight should go on. In this case, it does.

Warmup

After medical school, Alessi began his practice working as an athletic trainer at Mount St. Michael Academy in the Bronx, eventually opening a neurology practice in Norwich, Connecticut. He started working with the Yankees' Double-A team there and noticed during his hospital shifts that he was looking at many baseline, prefight brainwave EEGs for boxers scheduled to fight at Mohegan Sun Casino.

"The Connecticut boxing commissioner invited me to come down to watch a fight," says Alessi.

"After the fight, he asked, 'How would you like to work with us?'

"I said, 'Do I get to end the fight?'

"He said, 'We want you to.'

So I've been ending fights since 1996."

Indeed, for the past 23 years, Dr. Alessi has served as the consulting neurologist during boxing matches at Mohegan Sun. He has gone on to study head trauma in other sports, how to measure recovery, how to gauge when an athlete is ready to return to play, and how to prevent head injuries.

But he got his start as a "fight doctor."

Alessi admits it's odd for a neurologist to work in a sport where a primary goal is to induce maximum cognitive impairment in your opponent — but that's exactly what makes his presence imperative. People who say anybody who fights in mixed martial arts needs to have their head examined can rest assured that it is — before, during, and after the fight.

"Some people are born with one pupil larger than the other, for example," Alessi says. "I need to know that before a fight because that's also a sign of concussion."

Sometimes fighters reveal things in the prefight interview that disqualifies them. "I once had a fighter who said, 'Yeah, I had surgery — I got a burr hole in the side of my skull.' I said, 'What are you talking about?' He showed it to me and I felt the hole. He said, 'Yeah, I had a brain hemorrhage, but that was years ago.' I said, 'You can't fight with that.' But he said, 'Well, they let me fight in [a different state].' I said, 'Are you kidding me?' Another guy I examined had a prosthetic eye. He said, 'Why can't I fight?' But with a glass eye, you obviously can't see a hand coming from that side."

"My job is to make sure all these guys go home alive. That's why I'm here."

Showdown

Despite the appearance of greater brutality, Alessi says mixed martial arts fights are less dangerous than boxing matches, with MMA fighters generating about half the average punching force boxers do, particularly when they're grappling on the mat and swinging from only a few inches apart, though as Carrington Banks could testify, a flying knee to the chin is a different story.

"In mixed martial arts, you also have the ability to tap out," says Alessi. "You can quit. There are various techniques, in mixed martial arts, where someone might get his opponent in an arm bar or a choke hold, and the other guy knows there's nothing he can do about it, so he taps out. In boxing, they can't quit, and the head is the primary target. But you'd be surprised how many times you go into the corner and the fighter doesn't want to come back out. That's the first question I ask them, and if they say no, I end the fight. He'll still get paid, and I've saved his life."

The American Academy of Neurology has backed off from its edict in the 1980s that boxing should be banned, instead calling for measures including more regulations and formal neurologic examinations for fighters. Alessi says more and more neurologists have gotten involved in the sport, screening individuals to determine whether they should fight.

Besides protecting individual athletes, Alessi has used boxing and MMA events as a lens through which to view the larger picture surrounding head trauma. "As the public awareness about long-term brain damage from concussions developed, I realized it was like I had my own lab," he says.

The world has known for a long time about the dangers of head trauma, the syndrome codified in 1928 when New Jersey forensic pathologist Dr. Harrison Stanford Martland published a paper in The Journal of the American Medical Association on fighters and coined the term "punch drunk."

Today, it seems that new findings on head injury are in the news daily. Since 2001, more than 60,000 scientific papers on chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and brain trauma have been published, raising awareness at both the public and professional levels, leading to protocols where athletes are pulled from games at the first sign of concussion. Trainers are taught to perform a SCAT5 (Sport Concussion Assessment Tool, 5th edition), elaborating on the questions the old cigar-chomping cornermen used to ask fighters between rounds: "What's your name? What day is it? Do you know where you are?"

The SCAT5 is used because the greatest and most immediate danger to concussion sufferers is second-impact syndrome, a fatal edema caused by a second head trauma sustained before the brain has had time to repair torn tissues, ruptured blood vessels, or damage at the cellular level from an earlier injury. Other organs have room to expand if they swell. The brain, encased in a hard shell, does not.

Time Out

"There's no such thing as a minor concussion," says Alessi, who teaches at the UConn School of Medicine. Of his three daughters, two are neurologists. "And as I tell students, if you've seen one concussion, you've seen one concussion. They're all different. In most cases, a single concussion should not cause permanent damage, but a second concussion, soon after the first, does not have to be very strong for its effects to be permanently disabling or deadly."

The problem with studying concussions is that you can't line up a variety of test subjects of various ages and sizes, take baseline measurements, and then hit them in the head with a 13-pound bowling ball moving 20 mph — the equivalent, experts estimate, to taking a punch from a pro boxer. You can't then compare those results to the results from hitting them with 6-pound bowling balls moving 40 mph, or to what the results would be if you hit them once an hour, or once a day for a month, or in the side of the head instead of the front.

"Ninety percent of the time, after a concussion, you wait 10 days and the athlete is going to be okay. But we still don't know what the long-term effects might be. We know how the cells repair themselves, but we don't know what kind of debris might be left behind once the cells heal," Alessi says. "A big part of my job is educating the athletes. That's really the best way to prevent these things."

After seeing patients at UConn Health Storrs most of the day, Alessi and a team of UConn Health doctors perform pre-fight interviews and health assessments at Mohegan Sun. Fighters are Carrington Banks and Mandel Nallo, who will face each other the next day. These checkups are essential. "Some people are born with one pupil larger than the other," says Alessi. "I need to know that before a fight because that's also a sign of concussion."

And yes, that is indeed a World Series ring it's from the 1998 New York Yankees; Alessi is a neurologic consultant to the team.

"There are only 1,800 professional football players. In college football, there are 54,000. In high school football, about a million. In youth football, you have over 3 million children. Another 3 million children play youth soccer, and a half million play youth hockey. So you have 7.5 million young athletes playing high-velocity collision sports, all with brains that are still developing."

Children lack both the myelin sheathing that protects older brains and the developed neck musculature that helps older athletes avoid injury. Alessi works with UConn student-athletes and teams and advises youth sports programs, because he is concerned for these younger athletes.

"They're smaller and they don't move as fast, so the force of impact is less, but they're more vulnerable," says Alessi. "We used to think if you let kids play full-contact sports, it will toughen them up — not true. The more contact you have, the greater the risk."

Requiring the presence of certified athletic trainers at every secondary school athletic event and training coaches on concussion symptoms are among the bare-minimum guidelines, which are endorsed by leading sports medicine organizations in the United States. Banning checking and headers in youth hockey and soccer and reducing full-contact practices to once a week for professional and college football have been linked to reduced injuries, Alessi says.

"You have to ask, what's to be gained from high-velocity impact at a young age? The fastest-growing youth sport in America today is flag football. Archie Manning [former pro-football quarterback and father of Peyton and Eli Manning] didn't let his sons play youth football. Tom Brady never played youth football. A lot of really good professional athletes in the NFL knew that they could build skill without getting hit," Alessi says.

"I tell students, if you've seen one concussion, you've seen one concussion. They're all different."

Main Event

Alessi has also been hired by the Western Sports Foundation to advise professional bull riders, traveling to their events six times a year. If a knee to the chin is enough to knock out a 155-pound martial arts fighter from Peoria, a head-butt from an enraged 2,000-pound bull is exponentially worse, as Hall of Fame bull rider Tuff Hedeman learned in October of 1995 when he rode a bull named Bodacious, regarded as the toughest bull that ever lived. Bodacious had perfected a trick where he would raise his hind quarters to throw a rider forward, then bring his head up and back. Bodacious butted Hedemen twice and broke every bone in his face, resulting in two surgeries and six titanium plates installed to repair the damage. The next time Hedemen drew Bodacious, he wisely allowed the bull to exit the chute without him.

"Bull riders are a different breed," Alessi says. "They're generally smaller, and they have greater core strength than any athletes I've ever seen, because you need that to stay on a bull. They get kicked or thrown or butted, but most of the time the damage comes from the violent whiplash they experience. In the old days, they just wore cowboy hats. Now about two-thirds of them wear helmets. We learned from the unfortunate circumstance where a young Canadian rider by the name of Ty Pozzobon passed away by suicide at age 25. The pathology found he had CTE."

Pozzobon was thrown and stomped by a bull in 2014, kicked so hard his helmet popped off. He was unconscious for 34 minutes and spent 10 days in the hospital. Pozzobon's tragic story forced professional bull riding, called the world's most dangerous sport, counting 18 fatalities from 1989 to 2009, to take a harder look at itself.

"The riders are very interesting guys," Alessi says. "I try to get to know them because the guys you see riding bulls this weekend may not be the same guys you saw last weekend, because there are so many tours. You may tell a guy, 'I don't think you should ride,' so instead of riding PBR [Professional Bull Riders], they'll go to some other lesser tour and ride. Like boxing. You tell some guy he can't fight, he'll think 'That's okay' and show up on a card in the Dominican Republic. When you talk to the riders, they all have interesting stories. You ask, 'Why did you become a bull rider?' 'That's what my father did. My uncles. My brothers. It's what we do.'"

Getting to know them is not the same thing as sympathizing with them, in contact sports where metaphorical hardheadedness can be an athlete's best and worst characteristic. Carrington Banks' desire to keep fighting is exactly what Alessi must guard against, where the heart of a champion, the sheer will to keep going and fight on, the very dimension of character that makes them a champion, is what destroys them in the end, fighting on into the later rounds of fights when they should quit, or fighting on into the later years of their careers when the body is too old to take it anymore.

Knockout

The next fight after Carrington Banks also ends with a knockout when a lightweight named Kevin "Baby Slice" Ferguson Jr. takes a beating from a fighter named Corey Browning. In a sport where participants are assigned cartoonish nom de guerres like "Big Country" or "The Monsoon" or "The Romanian Bomber," Browning is built like a guy whose nickname might be "Tech Support."

He nevertheless prevails over the ripped and chiseled Ferguson, whose nickname "Baby Slice" comes from his father, a legendary street brawler nicknamed Kimbo Slice, the man who put mixed martial arts on the map for both his ferocity and his theatrics. Like the sons of bull riders who seek to follow in their fathers' footsteps, there's something heartbreaking about an athlete who does something dangerous because it's the family business.

Personal narratives are not Alessi's concern. "Baby Slice" is carried out on a stretcher and still unconscious when Alessi loads him into the ambulance, and the subsequent fights have to pause briefly because there are no more ambulances. "I can't let myself feel sorry for a guy because it's his last fight, or because he really needs the money. Sometimes they expect a fighter to sell tickets to everybody from his gym, the way Girl Scouts sell cookies to their family members. So someone might tell me, 'You gotta let this guy fight — he sold 500 tickets.' Or sometimes, the more rounds a guy fights, the more he gets paid, so it's in the corner's interest to keep the fight going.

"I say no. That's not why I'm here. That's why I have the final say, and if I need to stop the fight, I stop it. I'm here to make sure nobody gets hurt. I've got one job, and that's to make sure every fighter here goes home alive."

Leave a Reply