No, Kanye, That's Not How It Happened.

Slave family in a field near Savannah, with a barrel full of cotton and dog lying in front, ca. 1860s. Stereograph File, PR 065-0081-0018, New-York Historical Society, 50482. Photography ©New-York Historical Society.

By Christine Buckley

Manisha Sinha's history lessons tell the truth about slavery in the United States.

When Draper Chair of American History Manisha Sinha was a child, growing up in India between Patna, one of the oldest inhabited places in the world, and Delhi, one of today's most populous cities, dinnertime was a lot like it is for most families. Or so she insists.

"Every family has its disagreements, and we were no different," she says. "We would argue about history over the table."

Sinha's father, Lt.-Gen. Srinivas Kumar Sinha of the Indian Army, and her mother, a Gandhian nationalist, often recalled stories from India's declaration of independence in 1947. She and her two sisters, one of whom also is an endowed professor of history and the other a high school history teacher, and her brother, India's current ambassador to the United Kingdom, were thoughtful children. Drilled into them at an early age was a passion for debate, grounded in the idea that no successful future is possible without understanding the past.

Perhaps it's no surprise, then, that this summer, when Kanye West called the 400-year legacy of slavery in the U.S. "a choice," Sinha wasn't having it.

Drawing on her decorated 2016 book, The Slave's Cause: A History of Abolition, she told Time magazine that West would do well to read the history, including the slave spirituals, that his own music stems from. "He ought to know that even when blacks were enslaved, their minds were not enslaved," she said. "When they did not have the right to vote, they voted with their feet."

The Slave's Cause, which was long-listed for the National Book Award for nonfiction among a half-dozen other awards, illustrates the many and often overlooked ways that slaves fought for their own freedom. Sinha's work teaches students, politicians — and yes, the odd celebrity — that history matters.

"These historical legacies — we still live with them today — and we must learn from them," she says.

A 'Typical' Immigrant

Sinha's light laugh lilts down the corridor outside her Wood Hall office. She has worked here since fall 2017, arriving from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, where she spent the first 20 years of her career and received that university's highest honor, the Chancellor's Medal. Before that, she attended Columbia for her Ph.D.; before that, college at Delhi University. Now, with the Connecticut breeze blowing her hair through the opened window, she notes that she's lived longer in the U.S. than in the country of her birth.

"It's a pretty typical immigrant experience," she muses. "I got my first job, my first car, everything — here in the U.S."

Her father, who would later be called "the thinking man's soldier" and a "sensitive, sympathetic, and enlightened general" by the press, spent his career wedged between a deep patriotism for his native country and a struggle for respect from Britain and its leaders.

As one of the first Indian officers in the British army, Srinivas argued in his writing — and at his dinner table — that it was of utmost importance for Indians to be represented in British institutions. Yet Sinha's mother, Premini, who wore only hand-woven Indian khadi robes and espoused the Gandhian principles of Indian patriotism and nonviolence, often challenged Srinivas' positive view of the British.

"My father said that Indians being in British institutions allowed for access to resources Indians might not have," says Sinha. "Yet then there was my mother, the Gandhian."

In part because of these discussions, Sinha held from early childhood a deep fascination with colonial India and its independence. She studied the writings of Mohandas Gandhi, and from there turned to the similar writings of Martin Luther King Jr.

"I became very interested in race in American democracy because of India's history of colonialism with the British," Sinha says.

"During the civil rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr. invoked Gandhi's idea of nonviolent protest. But in fact there were American abolitionists and thinkers who had used it even before Gandhi, like Thoreau in his Civil Disobedience."

At Columbia, her dissertation on slaveholders was nominated for the competitive Bancroft Prize and eventually became her first book, The Counterrevolution of Slavery: Politics and Ideology in Antebellum South Carolina (The University of North Carolina Press, 1994).

"After all that, I wanted to write a book about people I actually liked," she says with a laugh.

"These groups were already imagining the interracial democracy we live in today."

The Slave's Cause

In 2004, Sinha spent a year at the American Antiquarian Society on a coveted National Endowment for the Humanities fellowship. There she spent weeks reading abolitionist newspapers and experienced a true historian's thrill when she uncovered original pamphlets signed by prominent black abolitionist Martin Delany.

The culmination of this research, 10 years in the making, was The Slave's Cause. The book counters the position, held by many historians, that white abolitionists by and large delivered slaves from bondage through their own newspapers, speeches, and petitions. After all, how could slaves work on their own behalf when they were enslaved?

In fact, some of the earliest anti-slavery organizations were started in Connecticut, says Sinha. Slaves and black freemen were petitioning for emancipation here and in Massachusetts and New Hampshire as early as the Revolutionary era. These early black abolitionists' anti-slavery, desegregation, and racial equality ideals in turn influenced white abolitionist speakers and publishers.

"These groups were already imagining the interracial democracy we live in today," says Sinha.

But the bulk of our histories focus too much on white abolitionists as the savior of the black man. In many cases, she says, historians are too influenced by the perspectives of their primary sources.

"For too long historians of abolition have told its story in a fragmented fashion and continue to do so along the lines of race and gender," she writes in the book's introduction. "I have found them [traditional abolitionist divisions] to be far less important than the attention lavished on them suggests and highly conducive to the perpetuation of stereotypes that defy the historical record."

Sinha says that historical studies are now enjoying something of a renaissance, with the perspectives of traditionally oppressed groups, such as women and people of color.

"We've come to a point where we can tell big stories with many historical actors," she says. "Now, we can rise above telling simple histories. We can show that people who were excluded from formal politics could still act politically. We can tell representative histories."

A Big Year

The smashing success of The Slave's Cause surprised even Sinha.

"It blew my mind. I didn't think it would have this attraction outside academia, but it did. It was a big year for me."

On Sept. 14, 2016, The Slave's Cause was named to the National Book Award for Nonfiction long list, an honor given to only 10 U.S. books each year. In October, Sinha set off on a monthlong book tour in the U.K, with stops in Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh, Nottingham, and London. She was celebrating her birthday on Nov. 2 back in Massachusetts when her father called from Delhi. He wished her a happy 54th birthday but also mentioned that he'd just fallen.

"I said, 'Oh my God, have you called the doctor?'" remembers Sinha. "And he said, 'No, I wanted to wish you a happy birthday first.'"

Sinha flew to Delhi and spent a week with Srinivas in the hospital while he recovered from a successful surgery to mend a broken leg and hip. The parade of friends, family, and government officials who came to visit all heard about his daughter's glory.

"He kept telling everyone my book won the U.S. National Book Award, and I would say 'No, Dad, it's on the long list, it didn't win!'" Sinha laughs.

During that week, Srinivas touched up his recently finished autobiography and penned the last of a long line of op-eds, according to Sinha. With his prognosis for recovery good, Sinha said goodbye and returned to a country that had just elected Donald Trump president.

"I thought, that cannot be," said the self-described Clinton supporter. "And then I got the call that my father was back in ICU with sepsis."

He died a few days later, just short of his 92nd birthday.

So while her fellow National Book Award honorees spent a weekend in New York for the annual awards celebration, Sinha found herself back in Delhi for the funeral.

"We were all influenced by our father. He wrote more books than me and my sister combined," says Sinha. "I would video chat him in the mornings when I'd be getting ready to write. He really was my biggest supporter."

Srinivas's biography, Raj to Swaraj (War to Independence), was published posthumously in 2017.

GREAT DEBATES

On a crisp September day in 2017, in a classroom in Wood Hall, Sinha asks students in her History 3510: Civil War in America class to take sides.

Chaos had erupted in Charlottesville, Virginia, two months earlier, when a neo-Nazi march to protect Confederate monuments was met by anti-racist counter-protesters, one of whom, Heather Heyer, was killed. The flames of the national debate about Confederate monuments were fanned, and Sinha wanted her class to participate.

"I divided the room in half, and I said okay, this side must defend keeping the monuments, and this side must advocate for taking them down," she says. "It was a big challenge."

But by that point in the class, says Sinha, her students had read enough newspapers, speeches, and essays from the Reconstruction era when many of the statues were erected to understand the context of their construction.

"Because they knew the context, they did a fabulous job arguing with each other," she says. "They learned the history through direct engagement with sources, and that demands more of them."

There's always a waiting list for Sinha's class, and she loves teaching it, especially since the room is full of freshmen through seniors, who are unafraid to disagree with one another — or with her. She engages with students from all sides of the political spectrum, ensuring that they use primary documents to inform their opinions.

"Sometimes people will say: 'The war wasn't about slavery, but about states' rights,'" she says. "To that I say, I'm not going to argue with you about that, I'm just going to point you to the letters that Southern officials wrote to one another, trying to work out how to keep slavery alive."

These debates also teach students the relevance of the humanities, Sinha says.

"It's through these kinds of interactions that my students learn to understand the present moment, with context," she states. "They learn that history matters."

As the endowed James L. and Shirley A. Draper Chair in American History, Sinha is charged with enhancing the academic experience in early American studies at UConn. She inaugurated biannual symposiums in American history, with themes like Confederate monuments and history and the law. In spring 2019 it will delve into the Reconstruction era, the topic of her upcoming book. The symposium draws historians and public intellectuals from around the country, an exceptional experience for her students.

"I really get to know my students," she says. "It's a wonderful thing about UConn, that classes can be small and you can have real discussions. It helps me, too, by influencing my writing, because I can figure out where my audience is coming from."

A HISTORY PRESCRIPTION

Kanye West isn't the only public figure who could learn from her students' example, says Sinha. Precious few politicians seem to know their history, she says, including members of Congress and presidents. If she had her way, all presidents would read the complete writings of Abraham Lincoln.

"I would prescribe it," she says. "He confronted the worst crisis in this country's history. Presidents should learn from his humility and from what he understood as patriotism. It was not to triumph. It was not jingoism. He knew that the highest form of patriotism can

be dissent."

Sinha has written extensively in the popular press about historical parallels. She's likened the progressive politics of the Obama administration to equal rights gains during the Reconstruction era, and cautioned that those gains could slip away, just as Reconstruction gave way to the Jim Crow era.

"These groups were already imagining the interracial democracy we live in today."

Manisha Sinha Was Born to This

UConn's Draper Chair of American History grew up in India between Patna, one of the oldest inhabited places in the world, and Delhi, one of today's most populous cities. Her father, Lt.-Gen. Srinivas Kumar Sinha was known as "the thinking mans soldier" and became governor of Assam. Her mother, a Gandhian nationalist, often recalled stories from India's declaration of independence in 1947. One of her sisters is also an endowed professor of history and the other is a lifelong high school history teacher, and their brother is India's ambassador to the United Kingdom. She was kind enough to share with us some precious family photos.

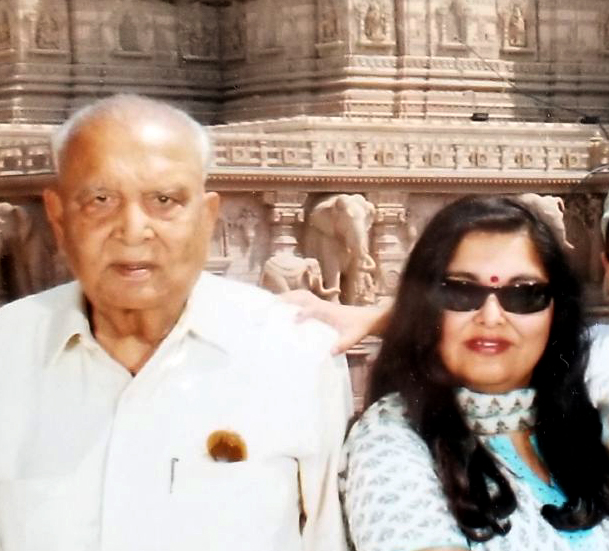

Srinivas and Manisha in New Delhi in 2010

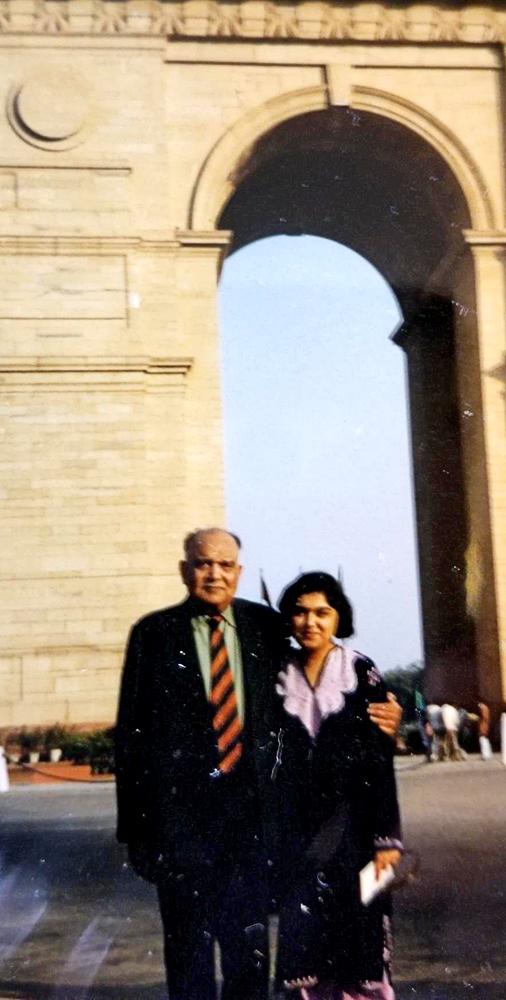

Srinivas and Manisha at India Gate in New Delhi, around 1987

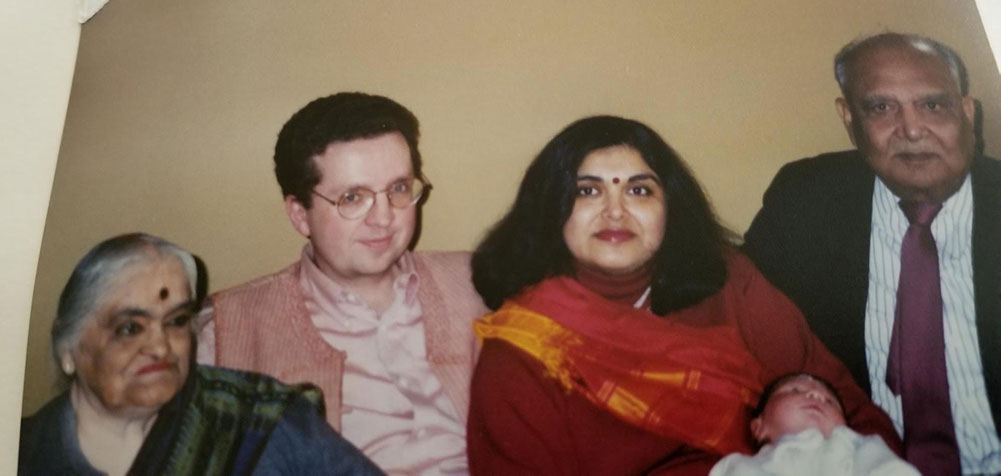

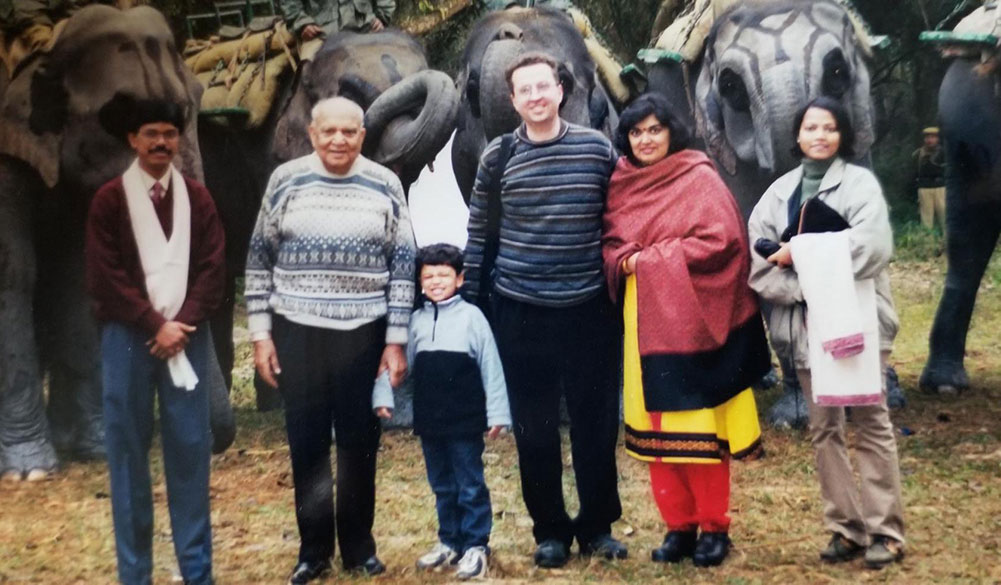

Lt.-Gen. Srinivas Kumar Sinha "was my biggest supporter" says Manisha

Family photos including, above, Manisha with her mother and father, husband and son

lying in bed waiting for five o’clock to arrive, bluetooth listening to an interview on npr, heard one with dr manisha sinha. my wife, a very light sleeper, reached over with her arm. she can tell from my breathing that i was awake.

as often happens when i get up, turn on the coffee machine to do its loud heat, rinse, grind procedure, i get on the web to look up something i learned during the night. this time it was dr sinha´s npr interview, her website, and some of her articles. very impressed.

thank you, dr sinha – and npr.