Can Truth Triumph?

Journalism Professor Amanda Crawford on Sandy Hook, Alex Jones, and Our Culture of Disinformation

By Amanda J. Crawford, UConn Journalism Professor

Illustrations by Karagh Byrne

It all started in a fever dream on a small sailboat off the coast of Jalisco.

Our friends set off a few months earlier to travel the world by sea. My husband and I joined them in southern Mexico for the first week of 2018. It was a time of transition in our lives, and we looked to the trip for tranquil respite on the cheap as we tried to figure out what came next.

The journey to meet them was long; we flew into Puerto Vallarta and then traveled several hours by bus. But when we set sail north along the Pacific Coast the next morning, everything seemed perfect. The boat cut a swift white line between indigo water and periwinkle sky. Wave-sculpted stacks of rock pierced the meniscus of the sea, and a humpback whale and her calf burst from the sparkling waves before us. That evening, we anchored in a near-empty lagoon and were lulled to sleep by the lilt of the sea.

When I awoke the next morning, though, the pressure in my head felt as if I had spent the night on the ocean's floor rather than bobbing along on top of it. My friends insisted I was just seasick and would feel better off the sailboat. So we piled into a dinghy to explore the shore and brackish channels thick with mangroves. As we sipped cerveza under a palapa in the sand, my eyes grew bleary, my lungs tightened, and my head throbbed. I could no longer deny the truth that threatened to disrupt this magical journey just as it started: the influenza virus I had contracted along the way took hold.

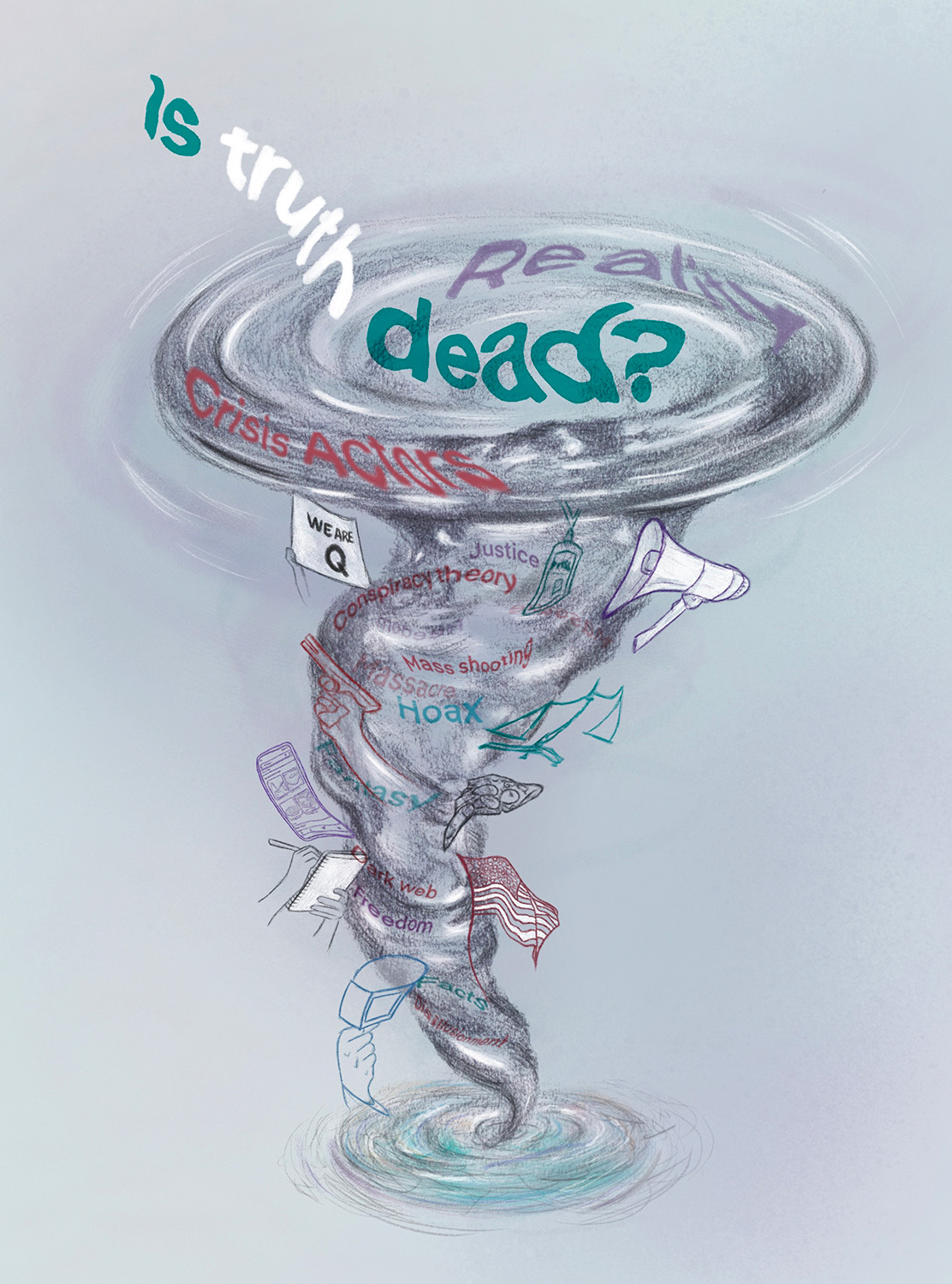

In the weeks leading up to the trip, I had been thinking a lot about truth. At the end of 2017, I certainly wasn't the only one. The 2016 election, marred by fake news and a Russian disinformation campaign, had delivered a presidency of "alternative facts." Time magazine asked on its cover, "Is Truth Dead?" President Donald Trump told more than 2,100 lies to the public his first year in office, an average of six a day, according to The Washington Post. Outrageous conspiracy theories and extremism poisoned public discourse as anti-vaxxers, flat-Earthers, and climate change deniers waged an assault on science. That August, hate and white nationalism had crawled out of the shadows and into the torchlight of the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. Then two of the deadliest mass shootings in modern U.S. history occurred just five weeks apart: 58 people were murdered at a concert on the Las Vegas strip in October 2017, and 26 were killed at a Texas church in November. The traumatized survivors — like those from almost every high-profile mass shooting since the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, five years earlier — faced heinous accusations that they were willing participants in a false-flag plot to take away guns.

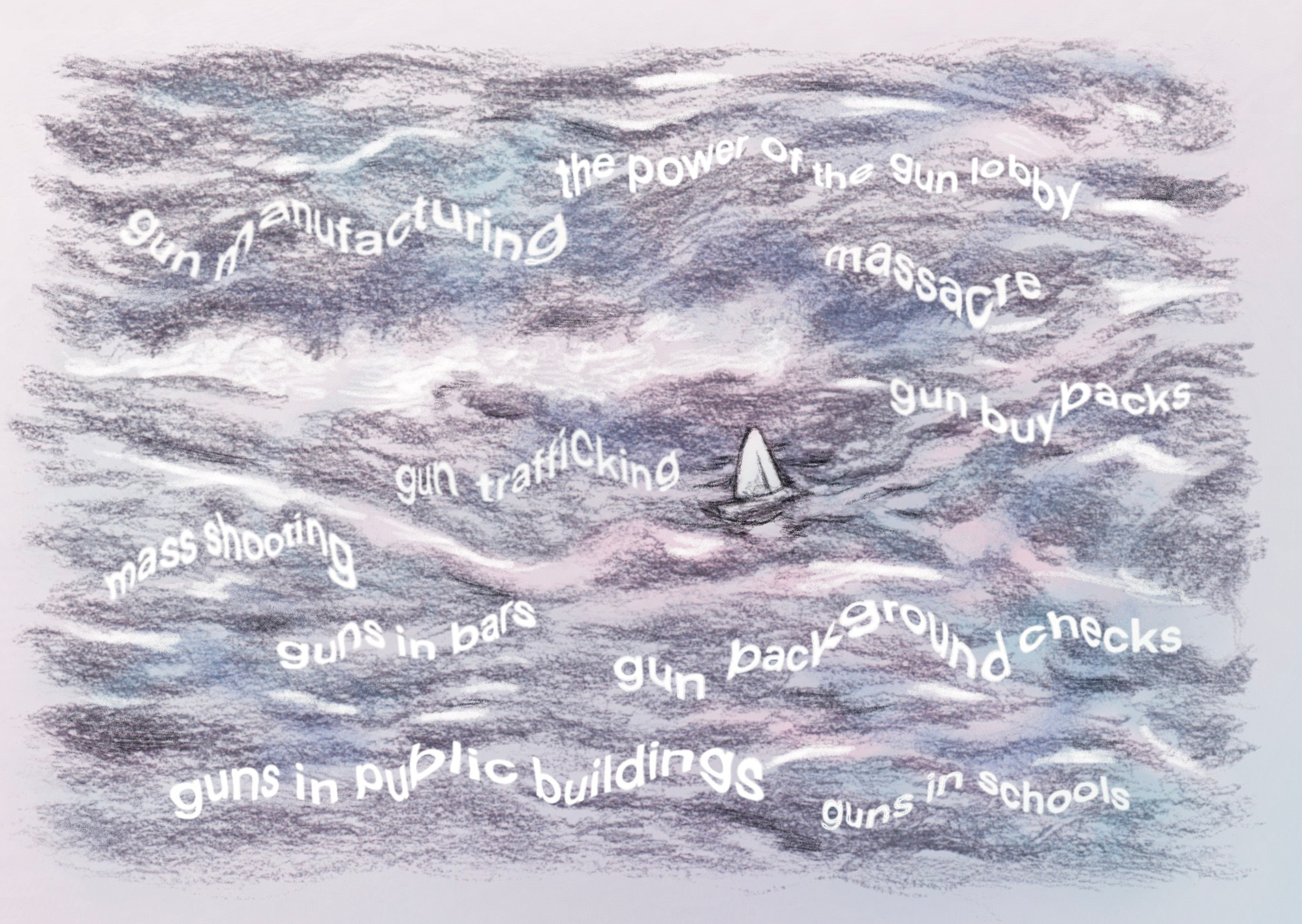

Of all the markers of the post-truth era, the cruel and politically motivated denial of these tragedies bothered me the most. As a journalist, I had covered several mass shootings, starting with one that had gravely wounded someone I had known for years as an Arizona political reporter, Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords. The shooting at Giffords' constituent event in a grocery store parking lot in Tucson in 2011 left six people dead, including a staffer, a federal judge, and a 9-year-old girl. I did not personally know any of the people who were murdered, but several close friends did and were shattered by the losses. After that, it seemed, the gun massacres didn't stop. I was in Aurora, Colorado, in July 2012 to report on a mass shooting at a movie theater there for Bloomberg News. A couple of weeks after that, there was a mass shooting at a Sikh temple in Wisconsin and, in December, the massacre at Sandy Hook Elementary School. I helped cover the tragedies and, in the aftermath, wrote a lot about guns: gun manufacturing, gun trafficking, gun buybacks, and gun background checks; guns in public buildings, guns in bars, guns in schools, and the power of the gun lobby. Changes to national gun laws had seemed all but inevitable after Sandy Hook, but within months even modest, common-sense proposals with broad bipartisan public support had failed in an increasingly polarized and dysfunctional Congress.

When Bloomberg News closed several regional offices, including mine, about a year after Sandy Hook, I was weary of gun violence and politics and was, frankly, disillusioned. I accepted a job as a journalism professor in Kentucky, a state neither my new husband, Toby, nor I had visited before my job interview. We settled into a creative nook in the Bible Belt, the college town of Bowling Green. There, we performed together in a band and opened a music studio and arts venue in the front of the green Victorian we rented downtown. I taught, gardened, and wrote about things unrelated to guns as political polarization worsened and America's mass shooting crisis continued.

Then, in early 2017, our little Kentucky town became the subject of a firestorm over fake news after Trump adviser Kellyanne Conway, on a TV news program, cited a made-up massacre in Bowling Green to justify the administration's ban on travel from several majority-Muslim nations. She blamed the media for people not knowing about it. It was ludicrous. (Later, she said she misspoke.) I penned a satirical response for The Huffington Post, and a friend, who thought it was funny, printed us a vinyl banner that stated simply in bold red and black type: "The Bowling Green Massacre Never Happened." We hung the quirky testament to our town's moment in the fake-news spotlight from the edge of our front porch. Tomato plants grew over the banner that summer, and we often forgot it was even there.

Then, in December 2017, an angry, shaggy-haired stranger drove to our house and parallel parked out front. When he saw one of our acquaintances on the porch wearing a local government windbreaker, he started shouting about deep-state conspiracies. When Toby came out, the stranger pointed at the sign: "Are you still butt-hurt about Trump?" he yelled. Then he grabbed my husband, who was standing five tall concrete steps above him, and pulled him down onto the sidewalk. The men tussled on the ground, and the stranger landed a hard kick against Toby's head. Eventually, Toby was able to pin him and call the police. (The man was charged with a misdemeanor.) The local newspaper wrote about the incident and people reminded us over and over again how lucky we were that the man didn't show up with a gun.

Then, the backlash started on social media. People called us "libtards" and accused Toby, who was left bloodied and bruised in the encounter, of beating up an innocent Trump supporter who was minding his own business on a public sidewalk. A middle-aged blonde woman who ran a booth in an antique store where I frequently shopped sent me dozens of vitriolic social media messages telling me we deserved to be attacked.

"You should be doing things to unify the community," she wrote. "If you care so much about fake news, why don't you do something about it?"

We ran a nonprofit that organized community arts events. I taught journalism and coordinated the university's First Amendment Studies program. I tried to reason with her. This was not a nameless troll. It was someone in our community. But it was no use. The woman's nasty messages and posts on our social media pages continued until we blocked her.

A week later, I was sick on the deck of the sailboat in Mexico. As my friends swam in the lagoon, thoughts about truth, democracy, fake news, conspiracy theories, online cruelty, and real-world violence swirled in my feverish skull.

I had become a journalist because I believed in the essential role of a free press in democracy: to seek the truth, hold those in power accountable, and empower the people for self-governance. I had walked away from organized religion many years ago, but my faith in the power of truth — and the concept of the marketplace of ideas that is the foundation of modern First Amendment jurisprudence — had never wavered.

But the marketplace of ideas had never been as free as it was after the advent of social media. Suddenly all the gatekeepers — journalists, publishers, universities, scientists, government officials, and other institutions that had previously vetted ideas before their mass distribution — had been sidelined. Truth competed online with an infinite number of outrageous ideas. Vicious hate speech, fake news, anti-science gibberish, odious conspiracy theories, hoaxes, and the manifestos of madmen zoomed around the world to billions of people in a flash and were promoted by computer algorithms that favored controversial content that spurred engagement without any regard to its social value or veracity.

The air temperature reached toward 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and my internal temperature soared even higher as I fretted about the incredibly high stakes for our society and our democracy. I closed my eyes against the sunlight. There is a quote that I often share with my students when I lecture about free expression. It's from John Milton's essay "Areopagitica," an early argument in favor of a free press, written in 1644. It is a bromide that I have turned to over the years just as others take comfort from their favorite Bible verse:

"And though all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so Truth be in the field, we do injuriously "¦ to misdoubt her strength. Let her and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter?"

A hot breeze rocked the sailboat, lulling me in and out of consciousness. All the winds, I thought. All the winds. Abstract notions took shape in the pastel dreamscape of my mind, and I watched Milton's words play out on a battlefield. It was an impressionist depiction that only makes sense within the omniscience of dream: a bundle of color that I knew to be Truth, beset on all sides. Battered by armies of wind. All the winds of misinformation. A tempest of fake news and propaganda. Winds of hate. Winds of willful and wanton ignorance.

It was the second decade of the third millennium, and all the winds were blowing. They blustered along the superhighway of information, gained strength in the chasms that divided us, and rattled the very foundations of our democracy. Truth was in the field, but she was bloodied. I was not alone in doubting her strength.

When I got home, I tried to organize the thoughts the fever dream had inspired — and sort out what this meant for the direction of my research. I knew every generation had carved out the parameters of acceptable speech in consideration of the most odious ideas of the time. I could think of no conspiracy theories more odious than the denial of the uniquely American horror of public mass-casualty gun violence and the cruelty to vulnerable people that those false narratives inspired. Just over a month later, on Valentine's Day 2018, another high-profile school shooting in Parkland, Florida, brought mass-shooting denial back into the limelight. In the aftermath, teenage survivors, whose calls for change reinvigorated the gun policy reform movement, were viciously pilloried online. Soon after, families of Sandy Hook victims filed lawsuits in Texas and Connecticut against rightwing disinformation purveyor Alex Jones of Infowars. For years, Jones had told his audience of millions that the mass shooting in Newtown was a government-staged hoax to take away guns — and encouraged them to investigate it. Families that had endured a horrific tragedy and suffered an unfathomable loss were accused of being "crisis actors" in the deep-state plot. They were harassed and threatened online, and sometimes confronted in person, too. Jones has claimed he was just asking questions, reporting on internet rumors, and exercising his free speech. But while opinions are protected under the First Amendment, defamatory false statements — like the many Jones had made over the years insisting that there was proof of a hoax at Sandy Hook — are not protected and are punishable under the law.

Around the same time the lawsuits were filed, I was offered an assistant professorship at UConn. In August, as my husband and I settled into a rented colonial in the Quiet Corner, several social media companies acted in near unison to ban Jones, Infowars, and others who had spread hate and misinformation on their platforms. As outcries over censorship went up from the right, I knew I had found the battle between conspiracy theories and truth that I wanted to chronicle. I thought by examining this dark corner of the misinformation crisis, I could shine light on many of the existential challenges facing our nation. I began interviewing people who had been directly impacted by the conspiracy theories, including victims' family members, survivors, local residents, first responders, and members of the clergy.

Among those I connected with was Lenny Pozner, the father of Noah Pozner, the youngest and only Jewish victim of the Sandy Hook shooting. Pozner has made it his life's mission to fight back against those who claimed Noah and other victims never existed.

"I felt like I needed to defend my son," Pozner would later explain in court. "He couldn't do that for himself, so I needed to be his voice."

At first Pozner, whose journey I later chronicled for Boston Globe Magazine, had tried to reason with deniers — thrusting himself into hostile online forums and releasing his son's personal records as proof Noah had lived and died. But he soon realized his truth didn't stand a chance against the onslaught of lies. So Pozner started a nonprofit called the Honr Network and recruited a team of online vigilantes to wage war with trolls on social media and flag hoaxer content for copyright claims or violations of internet company guidelines.

By the time I met Pozner in person for the first time in Florida in early 2019, he had become an expert in the opaque rules of the private companies that control so much modern public discourse. He kept his son's Batman costume and small flip-flops in his drawer so he would see them every day when he dressed, then he crossed his apartment to his computer, where he spent hours every day skimming through hateful content trying to preserve his son's memory. He and his volunteers had succeeded in getting thousands of social media posts and blogs deleted from the web, and he had helped persuade several platforms to change rules to block denial of tragedies like the Sandy Hook shooting. But his success had come at a cost. He faced continuous harassment and even death threats. He had moved a half-dozen times, altered his appearance, and lived in hiding.

The day after I met Pozner, I drove across Florida to meet with a man who had been Alex Jones' lead "expert" on Sandy Hook. A one-time cop and school employee, the retiree had spent years tormenting Newtown officials and victims' families and targeting surviving children with outlandish claims. He handed me a background check on Pozner, convinced the grieving father was a deep-state operative. I later met and wrote about another leading Sandy Hook conspiracy theorist, a retired philosophy professor and Holocaust denier who Pozner successfully sued for defamation in Wisconsin. Though the man fancied himself a champion of academic freedom, he sent a letter to UConn's leadership trying to get me fired after I wrote about his trial for The Chronicle of Higher Education. He enumerated 26 complaints about my conduct, one for every letter in the alphabet. Among his strikes against me was speculation that I might be Jewish since I once spoke at a Hartford synagogue.

The further I got into my research, the more concerned I became about where misinformation could lead. Initially, some of my friends, family, and colleagues questioned whether deepstate conspiracy theories were really that widespread. But I continually ran into normal people around the country, and even in Connecticut, who proclaimed with certainty that the Sandy Hook shooting didn't happen. Normal, workaday people who didn't spend their days in alt-right forums or trying to reach the darkest corners of the web. There was the waitress at a Cracker Barrel in Florida. The bartender and the cook at our favorite Connecticut bar. My husband's friend of more than 20 years. The doubts about Sandy Hook, though thoroughly debunked, had permeated mainstream society and fed distrust of the media and the government in ways that had fractured our common perception of reality.

I became increasingly worried that conspiracy theories like this would lead to political violence. But even as I pointed to the growing number of "Q" signs at Trump rallies — a reference to the absurd QAnon grand conspiracy theory about the deep state — many people I talked to didn't believe these outlandish notions could have much of an impact. "What happens to democracy if members of Congress promote these kinds of outrageous false beliefs?" I asked. I had no way of knowing at that time that conspiracy theories would lead to a violent insurrection at the U.S. Capitol, but I felt certain that they would continue to spread online and cause escalating harm in the real world.

Since then, we've all lived through a global pandemic made worse by false beliefs that it was a government hoax. The "big lie" that the 2020 election was stolen was promoted by Trump, right-wing news outlets, members of Congress, and elected officials across the country. The election lies along with the QAnon conspiracy theory led to the deadly attack on the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, that sought to block the peaceful transfer of power for the first time in our country's history. The entire nation now seems to be transfixed by the fight against misinformation and debating the future of free speech in the digital era.

Though I believe that there are still many challenges on this front ahead, I do see hope for the future. Many people have awakened to the dangers of false beliefs and, as the results of many 2022 midterm contests showed, are rejecting candidates who cater to extremism and promote election lies. As someone who studies media law, I also see hope in the American judiciary. The final bulwark in the defense of reality, judges and juries in courts around the country are starting to weigh in by punishing those who spread lies that defame and cause real-world harm. As I write this in late 2022, Jones and Infowars have been hit with judgments of nearly $1.5 billion in lawsuits by Sandy Hook families. And courts around the country are taking up cases against those who have promoted election lies and other conspiracy theories.

All the winds are still blowing, but I continue to have faith in the power of truth.

Amanda J. Crawford, an assistant professor of journalism at UConn, is writing a book that explores the dual crises of misinformation and mass shootings. You can find links to her recent work at journalism.uconn.edu/amanda-j-crawford.

We can only hope and pray that education will win out over disinformation. It will be difficult as we see a US Representative from New York who is unable to tell the truth about anything being accepted by his fellow party members. Marvin Horwitz ’51

Thank you for your efforts on behalf of Truth. I will be looking for your book. I hope that you can make a difference.

R. Newlin ’71 (SSW)

“And though all the winds of doctrine were let loose to play upon the earth, so Truth be in the field, we do injuriously … to misdoubt her strength. Let her and Falsehood grapple; who ever knew Truth put to the worse in a free and open encounter?â€

“…several social media companies acted in near unison to ban Jones, Infowars, and others who had spread hate and misinformation on their platforms.”

Quoting Areopagitica in defense of a state-sanctioned truth is fairly ironic. We aren’t in a free and open encounter, thanks to public-private censors and complicit journalists. Every journalist needs courage, and it takes none to regurgitate a press release that the Washington post already regurgitated. It is necessary to the continuing of this nation that journalism students are encouraged to take official statements as PR instead of facts, especially in cases where official statements lead to ammending the constitution.

This country is like a piece of paper that the press is helping to fold, waiting for the next tragedy to tear it in half along the crease. Every preconceived message of unity fed to Americans contains a qualifying statement that plants more partisan BS in people’s minds and sets the stage for the next tragedy to be even more divisive. Let the truth prevail in a free and open encounter. “Reading scripts to consumers” is not an acceptable replacement for “speaking truth to power”.

Please use me as an example for your students of a misinformed individual. You can explain to them that I haven’t ever watched Alex Jones, I don’t have social media, and I did not vote for Trump. I am replying to this op-ed because it was delivered to my inbox unsolicited, and I read it.

Ryan

From your fever dream to God’s ear…or however that saying goes. Thanks for this work and continuing to fight the good fight — particularly since it really shouldn’t be an actual fight. Hope you and the fam are well! —Stacy Pearson

Dear Professor Crawford,

I have just finished reading your article in UConn magazine and found it to be profoundly meaningful.

Do I have your permission to pass this on to friends and family?

Best of luck to you.

Steve H Danbom, Ph.D.

UConn, 1975

After receiving the latest issue of the magazine and reading the article written by Amanda Crawford I was deeply disturbed. The point of view expressed by a journalism professor that we are living in a “post truth era” due to “anti vaxxers, flat earthers, and climate change deniers,” not only paints those weary of injecting themselves with an unknown medicine with the same broad brush that actual science deniers are painted with, but also embodies the exact “anti truth,” sentiment the professor is claiming to have so much disdain for.

Prof. Crawford has clearly fallen into the same trap that so many other journalists have in the past couple years, supporting censorship if they personally disagree with the opposing belief. I am sure this email will not be shared at the editors discretion for the same reason. Prof. Crawford shares the belief that the solution to gun violence can be legislated into effect. This belief is shared by those naive and not dealing with the matter day in and day out. It is a belief shared by those who operate in an academic vacuum, rather than out in the real world. A lovely sentiment, but one that is not reality. Having said that, I fully support Prof. Crawfords ability to express this opinion. That is where she and I differ and the “anti truth” spotlight shines on her.

It was both interesting and concerning that the Professor does not mention the actual path to fixing the gun violence problem; mental health funding and focus, coupled with a justice system that holds offenders accountable which CT is currently lacking. Instead she spent more time detailing her vacation to Mexico.

There has undeniably been an “anti truth” campaign as of late. For example, I am sure you have not read the latest statistics that show Vermont, one of the most CV19 vaccinated state per capita in the US, now has the highest non-Covid death rate they have experienced in years, post pandemic. Additionally the acknowledgement of Twitter that conservative pundits and view-points were purposely suppressed by the current presidential administration’s FBI.

Again, I am sure this will not make it past your email server as it is a viewpoint that seems to conflict with that of the magazine, but the right to express opinion, no matter what is, seems like something a Journalism professor would want to protect.

Regards,

Anthony Miele

CAHNR 2011

Anthony,

We’re on the same page. Read my comments (below yours, I believe).

First, I am not a Sandy Hook denier, but I am a right-wing extremist in the eyes of Amanda Crawford. I believe in the plain statement of the 2nd Amendment, “A well-regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.†Simple words even a journalism professor (or major) can understand.

People on the Right are as aghast at shooting massacres as people on the Left. The disagreement arises in the solutions offered by the two parties. The Left wants to deny law-abiding (actually Constitution-abiding) citizens the right to own so-called “assault weapons†(semiautomatic rifles), going so far as to ban ownership in New York and Connecticut. The Right asks why the great majority of law-abiding gun owners should be held responsible for the acts of an evil few. The Right would arm teachers and staff, thereby hardening them, so that evildoers would be met with violent resistance. (Read In Defense of the Second Amendment by Larry Correia for more information on gun rights.)

While New York and Connecticut have banned possession of “assault weapons,†their state police have not gone door-to-door confiscating weapons. Why? That would be an abrogation of the 2nd and 4th amendments to the Constitution. Such endeavors would be met with armed responses, causing a 2nd civil war. Stomping on the Constitution is a big deal for us conservatives.

Crawford writes about right-wing so-called lies and disinformation, but she did not delve into the deep-state attempt to harass and intimidate Donald Trump with the false premise of Russia collusion in the Democrat-sourced Project Crossfire Hurricane. And as for the so-called “big lie†that the 2020 election was stolen? Well, I have watched many presidential elections in my lifetime. When I went to bed at ~1:00 AM (west coast) on November 4, 2020, Trump was ahead by ~100,000 votes in Pennsylvania. The next morning, Trump was suddenly behind. Such a margin is usually whittled away over several days, not in, say, seven hours’ time. For one modus operandi, see the documentary 2000 Mules by Dinesh D’Souza.

Another point. Why is UConn Magazine publishing political screeds? I have seen articles on Senator Chris Murphy (a liberal Democrat), reparations, 1619 Project, and now Crawford’s leftist polemic. Are all your readers liberal? UConn, once a great and prestigious university, seems to have suddenly become a Leftist, Woke harridan, scolding and proscribing conservatives. If you lean Right, do not donate to UConn.

Finally, to co-opt and revise Mark Twain’s quote, “There are lies, damned lies, and Democrat talking points.â€

Frederick Su

Ph.D., Physics, 1979

Ex-Marine, 1969-71

I noted with interest the above article in the latest UCONN Magazine. However, as I began reading it, I was appalled at its extreme left-wing bias. The writer claims that Donald Trump “told more than 2,100 lies” and then conflated his presidency with “flat-Earthers” and other ridiculous comments.

So did the writer have a clicker to click for every supposed “lie”, in order to reach an exact count?

Trump may be guilty of exaggeration, but if he were ever to be caught in a serious lie, it would still not even hold a candle to Biden’s long, long record of verified lying, as well as plagiarism, which cost him his 1988 run for the presidency.

The public’s memory is short, however, and many voters too young to know about his prior poor behavior. However, he continues to tell lies–outlandish stories designed to pander to whatever audience he is trying to impress. As well as such bald-faced lies, such as “the Border is secure.”

I have fond memories of UConn, but it saddens me to see that the school has taken a sharp left turn, and continues to fan hatred of a great president, Donald Trump.

Sincerely,

Amy Lamborn ’84 (CLAS) History

I read with interest the article “Can Truth Triumph?” in the Spring UConn Magazine. I expected the article would promote something that is very obvious to many of us we need journalism and other media to expose lies without bias so the real truth can be found.

The article left me very disappointed due to its obvious liberal bias regarding the culture of disinformation. Are there no examples where disinformation was propagated by liberal individuals and politicians? Of course there are. Unfortunately, no such examples were offered in this article about “truth”. It should be no surprise why journalists and other media are so distrusted by a large percentage of Americans. Liberal narratives are to be considered “Truth” and anyone who questions them is a “conspiracy theorist” who spreads “disinformation”.

We need journalists and other media to question everything without bias to seek the real truth. As long as liberal bias continues to be the norm, the real truth will be hidden from us all.

Bob Kroll, MBA 96

I enjoyed reading your article “Truth is Dead†in the current issue of UConn Magazine, and wanted to thank you for your integrity as a journalist and for standing up against some of incredible misinformation/disinformation/BS that continues to pollute the mindscape.

—Thomas Terry, UConn faculty 1969-2003, Molecular & Cell Biology