The Ortega Effect

Many hundreds of UConn alums — firefighters, photographers, biologists, inventors, park rangers, brewers, and so many more — credit this one brilliant, patient, unassuming professor for helping them cut through their confusion and fear to steer a purposeful course through college, work, and life.

By Kim Krieger

Illustrations by Monique Aimee

Portrait by Peter Morenus

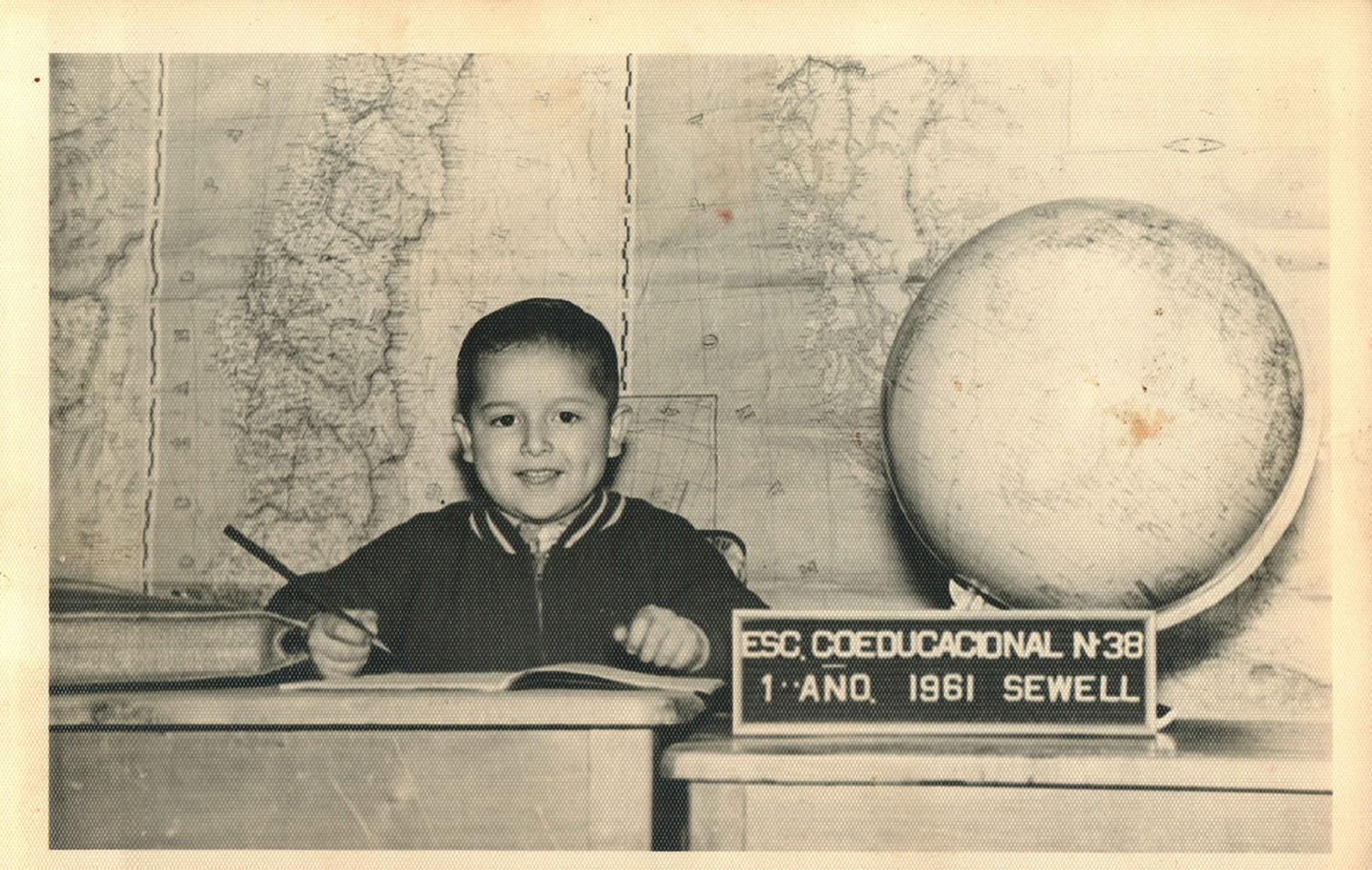

Ortega at age 6 in Sewell, Chile, where his father worked the copper mines and helped his mom raise five children, spurring all to college degrees.

The mountain lion looked at Morty Ortega, and Ortega looked at the mountain lion. The lion wanted the four guanacos that had run up to Ortega in search of protection. But the predator eyed Ortega appreciatively, gauging how much of a fight he would put up if it went for one.

Ortega isn’t a big guy, but he has a quiet confidence that guanacos and college students alike find reassuring, whether they’re in the hills of Patagonia or the classrooms of Storrs.

This was not the first time Ortega had looked a mountain lion in the eye. He raised the tripod he was holding. The lion decided it would find easier pickings elsewhere, and took off.

Ortega spent years studying guanacos — small, wild relatives of the llama — and knows their habits and ecology the way a father knows his children. He has spent a lifetime studying the social behaviors of large mammals. And though the ecologist loves big cats, giraffes, elephants, and other exotic megafauna, the mammals closest to his heart are found all over Storrs.

Ortega began his career focusing on wildlife ecology, but over the years he has found a second avocation focused on students. Call it finding the diamonds in the rough — students who might otherwise be overlooked, even fail out. Ortega picks them out of the crowd and nurtures them until they can face down those mountain lions on their own.

“It’s easy for me to spot them because I see myself in them,” Ortega says. Shy as a youth, he grew up in the high desert town of Sewell, amid the copper mines of Chile where his father worked. He recalls no animals in Sewell, not even domestic cats. Neither of his parents attended high school, but they wanted him to be a doctor or a lawyer. However, a good science teacher and mentor, using a neglected schoolyard garden as an ecology lab, set Ortega on the path to research and mentoring.

When he arrived at Universidad Austral de Chile in Valdivia, Chile, he recalls the professor directing the bachelor of science program telling him,“I don’t see you finishing the semester. You probably will be gone.”

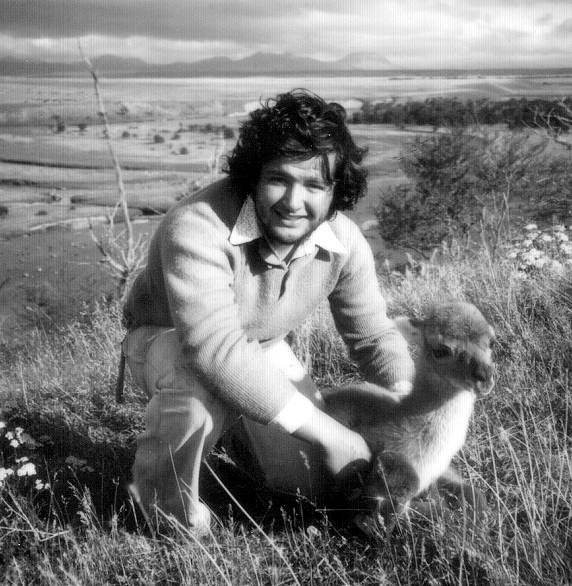

At 20 on the island of Tierra del Fuego, Chile, with a baby guanaco. A local sheep herder brought the chulengo to Ortega’s group, saying they should learn about guanacos by raising one.

At 25 in Torres del Paine National Park in Chile’s Patagonia region, studying the guanacos who live in grasslands shadowed by bright blue glaciers.

“I am teaching [my kids] to get outside ... and explore ... with an always positive attitude. This world has a lot to offer, and Morty showed me that.”

—Ryan Gernat ’06 (CAHNR).

That professor was wrong, and other professors soon saw Ortega’s potential. Sophomore year, his histology professor actually asked him to teach a class. When he proved himself capable, she offered him a place in her lab if he would continue to teach.

Ortega does the same, offering students who risk getting squeezed out of the University a space of their own, whether it be a desk in his lab or a mirror for self-reflection.

Kiernan Sellars ’20 (CAHNR) was adrift as a UConn undergrad when Ortega suggested she consider the sciences. She remembers that only after she had her natural resources degree in hand did Ortega admit he’d feared she’d drop out. A good professor knows when to stay silent and offer support. Sellars now works at Waldo County Bounty, providing Mainers access to fresh, nutritious food.

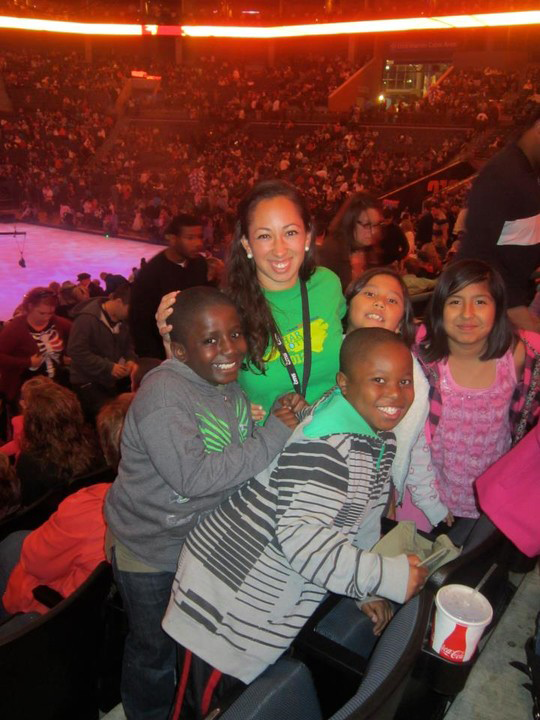

“Morty’s office was my safe space,” says Carly Congdon ’13 (CAHNR), who describes her mental health in her early 20s as poor. “I didn’t feel good enough. I had a lot of self-doubt,” she says. She started going to Ortega’s office to cry. Ortega would listen. Sometimes he’d ask her questions. Her answers reminded her she was good enough — good enough to be at UConn, to major in a science, to go on and be successful. After earning her degree, she moved to Oregon to study sea birds and migratory fish. Later she began to work in social services, became the associate director of a public housing program in central Oregon, and is now getting a graduate degree in social work.

In his early 30s at Texas Tech in Lubbock, Ortega earned a Ph.D. that involved studying the feeding habits of white-tailed deer sharing range with cattle. He raised the deer by hand, protecting them from rattlesnakes and other hazards. Texas Tech is where Ortega taught his first class — and was permanently smitten.

“When somebody shows you compassion and empathy in your darkest times … you can take that experience and offer it to other people,” Congdon says. She always reminds her clients they are good enough.

When Ortega was pursuing a master’s degree at Iowa State University, he was told he could not teach because his accent was too heavy. He knew he could teach from his experience as an undergrad, so when he moved to Texas Tech in Lubbock for his Ph.D., he asked again, and was assigned to teach a summer course on environmental science. “I just loved it. I put a huge amount of time into putting lessons together.”

His teaching style has evolved since those days in Lubbock. Back then, he lectured, used slides, and encouraged note-taking. These days, it’s different.

Congdon (in green) on the 2012 study trip to Entabeni Game Reserve in South Africa. Hoogenboom was on the 2016 Chile study trip and returned to Torres del Paine six years later.

“There are 80 to 100 students in the classroom, and I say OK, here’s a few things. You are not allowed to take notes. Your phones have to be off. Your computer has to be off the desk. You are not allowed to have anything in your hands. You are going to listen. You are going to use something that you have called your brain, and we’re going to discuss things. The famous Socratic method. At first they get very scared,” Ortega says. But then they get into it.

He posits seemingly random questions, like asking them if they think about penguins when they are taking a shower. He then asks the students to explain why this might happen. And in so doing, he engages their minds and teaches them everything is connected in ecology, because the planet is our home. Even the name of the science combines the Greek roots oikos (home) with logos (study).

Ortega gets his students to see more of their planetary home on trips to national parks and wildlife refuges in South Africa, Patagonia, and the United States. On these trips he insists that students keep journals describing everything that happens.

“In one of my classes with Morty, we drove around for 18 days,” visiting places such as Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota, says Ryan Gernat ’06 (CAHNR). “His excitement and knowledge of everything we saw along the way was amazing. He pushed me to want to get out in the world.” When Gernat graduated, he took a job in the pharmaceutical industry to pay off his student loans, but he made sure to keep his mind open. When he was offered the job of supply chain manager at Two Roads Brewing in Stratford, Connecticut, Gernat recognized the opportunity and took it, though it was not a career he’d previously considered.

“Now that I’m older and have kids, I am teaching them to get outside in nature and explore for themselves with an always positive attitude. This world has a lot to offer, and Morty showed me that,” Gernat says.

When Ortega was a Ph.D. student in Lubbock, he studied feeding behavior in white-tailed deer. He raised the fawns by hand but released them on the open range once they were past the baby stage. His advisor was incredulous, convinced that the deer would take off, but Ortega was confident they’d stick around. And they did stick around — for years — so that he was able to observe how the older deer allowed the younger deer to pull vegetation out of their mouths. The fawns learned what was good to eat directly from the mouths of their elders.

Sometimes students need that level of prescriptiveness. Summer Hoogenboom ’17 (CAHNR) knew she wanted to study wild animals but could not see a path to her goal — until Ortega gave her a map of classes to take. When she was ready, he suggested a research program to pursue. She went on to study wolves, and now, in addition to running her own internationally funded research, she is the major gifts officer at Zoo New England in Boston.

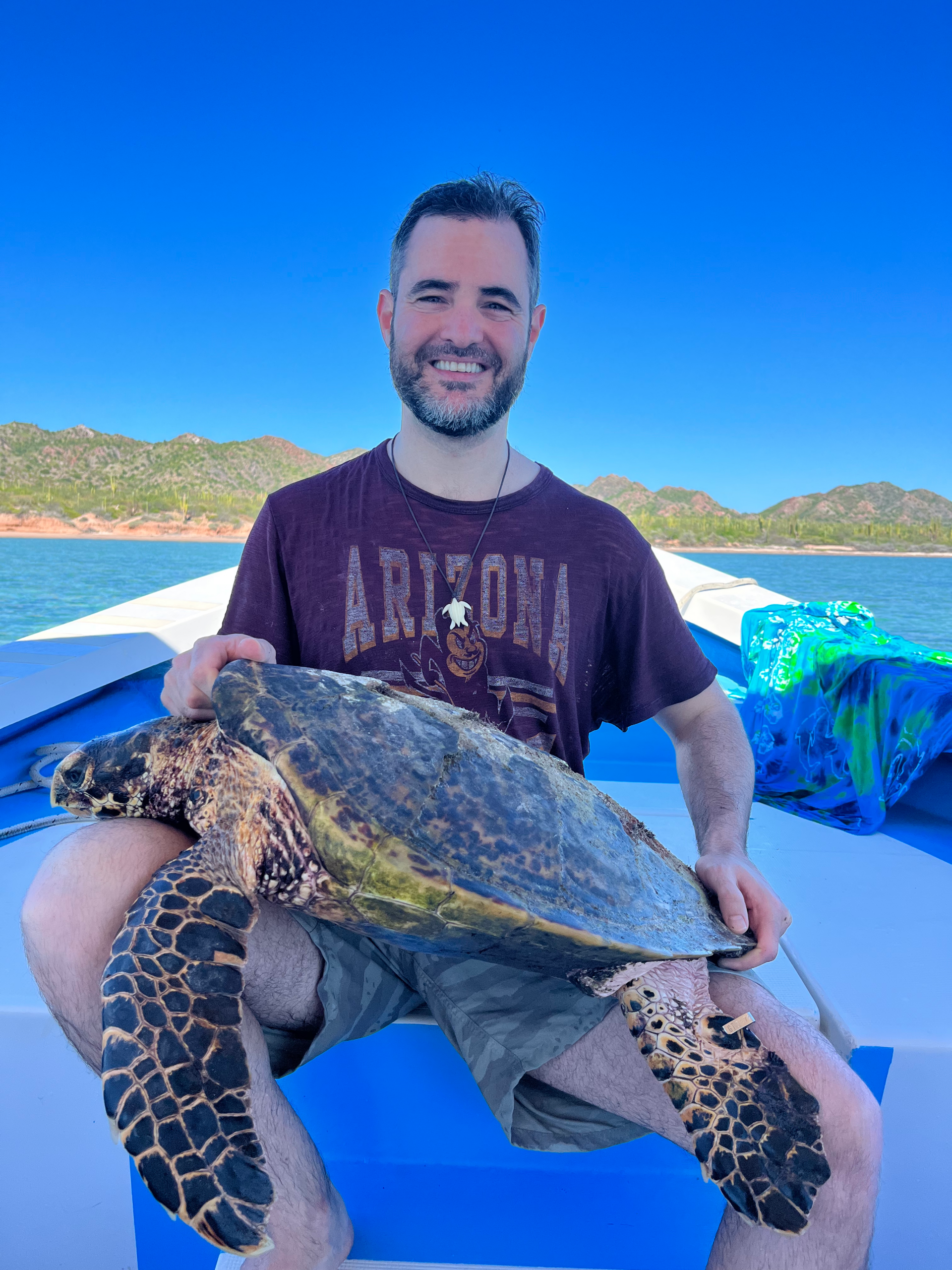

Jesse Senko ’06 (CAHNR) was interested in everything, but particularly turtles. He went to Ortega, who pushed him to do an independent study and apply to a turtle research program in Baja. A self-described middling student, Senko hadn’t seen himself as someone who could ever get into an elite research program. He is now a professor of marine biology at Arizona State University and works with fishermen in Mexico designing lighted nets to prevent sea turtles from drowning as bycatch in the Pacific. He’s not the only inventor among grateful Ortega advisees. Amelia Martin ’23 (CAHNR) started her company Mud Rat to devise an entirely ecofriendly surfboard.

Then there are the students whose careful plans go awry. Ortega hopes his process of listening to students talk until they can hear themselves think keeps them eager to explore.

Michelle Smyth ’15 (CAHNR) knew her course: go to UConn, study natural resources, then join the Air Force. But the Air Force fell through, and Smyth found herself in need of a job and direction. She woke up one morning on a camping trip in Montana wishing she could stay there. Instead of dismissing that thought as an idle fantasy, she heard Ortega’s voice in her head, asking, “Why not? Why not live in Montana?” Smyth stayed, becoming a park ranger and then a wildland firefighter. “I give Morty all the credit for that,” she says.

The Ortega Effect

“Morty has by far been my biggest career supporter. Throughout my years at UConn and even after graduation, he always had life-changing advice and encouraging words. He guided me through every step in my wildlife career and has played a huge role in all of my successes.” —Jaimie Simmons ’17 (CAHNR), photographer, former wildlife and manatee biologist

The Ortega Effect

“My interactions with Morty helped me to understand and envision what work and careers could be possible with a natural resources degree. Hearing about Morty’s extensive work with guanacos and participating in the South African study abroad program alongside him fueled my interest in field work and helped me decide the type of positions I was interested in pursuing.” —Samantha Kremidas ’13 (CAHNR), program analyst for the National Ecological Observatory Network (NEON)

Hunting in Montana these days, she will also call on the animal-tracking lessons she got from Ortega. “I go back in my memory and use the little tricks I learned. And I can use them to track the movement of a fire,” Smyth says. In her line of work, staying alert to the signs of nearby wildlife is key to staying alive. “I’ll see bear poop and be like ‘Heads up!’”

Being able to break through that box we all find ourselves in, the box that defines who we think we are, and what we think we can do, is Ortega’s goal for all his students.

“His passion for science, adventure, and the success of his students was simultaneously contagious and inspiring; a modern Dr. Indiana Jones,” says interim UConn fire chief Chris Renshaw ’01 (CAHNR). Renshaw says Ortega pushed him to consider other perspectives that challenged his biases. “I am forever grateful for the opportunities he provided me as a student, and his continued mentorship to this day; much of my success is owed to him,” Renshaw says.

Debra Feinberg ’09 (CLAS) agrees. “Morty always made time for meaningful conversations,” she says. “I distinctly remember one time sitting with him pondering what life after senior year might hold. I shared my dream of joining the Peace Corps or working overseas, but how having older parents who’d had health scares made me nervous about moving far away. Morty’s advice has stayed with me ever since — I shouldn’t let fear of the ‘what ifs’ hold me back. It was the push I needed to take a leap of faith when offered the opportunity to move to South Africa.”

It’s true that taking the time to mentor so many students — many hundreds so far — has taken a toll on Ortega’s research. He doesn’t publish as many papers or run as many international research projects as his peers. He has resigned himself to never making full professor. “In the long run, what is this for? You’re making some sort of an impact. You wrote a paper? Cool. You’re doing scholarship. But when you open the minds of people, they can jump into the right lane, and their whole life will be better,” Ortega says.

Ortega with Kremidas at the Entabeni Game Reserve in South Africa; with students in Patagonia in 2005 and in South Africa in 2025.

The Ortega Effect

“Morty always had an open-door policy to discuss crazy ideas and dreams and how we could find opportunities to make those things happen. He taught me the invaluable skill (which I was very bad at) of sharing what you want and what your goals are in your career and life, so people can help work with you to make those things a reality!” —Brittney Parker ’15 (CAHNR), senior resilience program manager at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

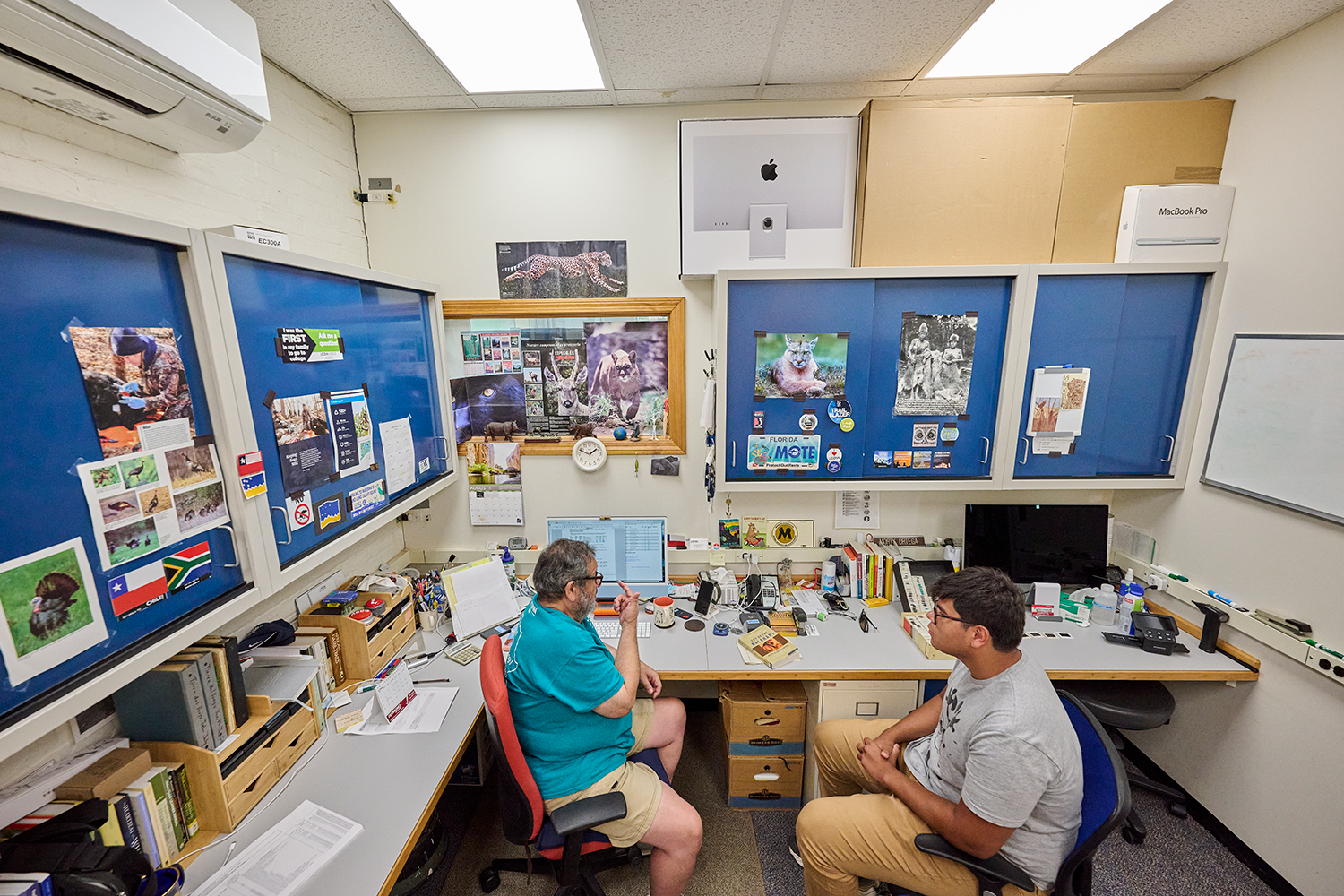

Many a career has been spawned over a cup of tea with Ortega in his Klinck Building lab. This fall, he talked grad school and/or geographical information systems (GIS) careers with natural resources senior Jandel Resto.

He remembers one night when he was alone in the camp at South Africa. The students had gone into the bush that day, while he conducted business in town. All of a sudden he heard steps in the dark. He grabbed a flashlight, and saw one lion going by, a second lion, a third lion, a fourth lion, and then a big male walking very slowly. “And I thought, this guy is going to come in here and probably is gonna kill me,” Ortega says. “My heart was going bupbupbupbupbup.” A minute later the game vehicles came back with the students, and Ortega ran to the gate and told them to be careful.

The lions were nearby all night. They killed a wildebeest, making all kinds of mess and roaring for hours.

The next morning, a student emerged from her tent as Ortega was lighting the campfire. “Morty, did you hear the lions last night?” she asked. “My God, they were roaring so loud! I don’t know if you heard anything, but they killed something because there was so much noise!”

“I thought she was very scared,” Ortega says. “Then she said, ‘Wasn’t that cool? I hope they do it again tonight!’”

Ortega laughs, and you see the pride.

“His passion for science, adventure, and the success of his students was simultaneously contagious and inspiring; a modern Dr. Indiana Jones.”

—Chris Renshaw ’01 (CAHNR)

Amazing story for an amazing professor! The Ortega Effect is real – and I am happy to say that our family includes one of the many students who have been positively effected by Morty. Thank you Professor Ortega!!

I’m so glad to read of your amazing stewardship of the students you have influenced. I’m so grateful that we were able to share so many adventures during the time spent in Chile studying the Guanacos with you. Your dedication and perseverance has been rewarded and you are passing that determination to achieve on to your students. Well done, Morty