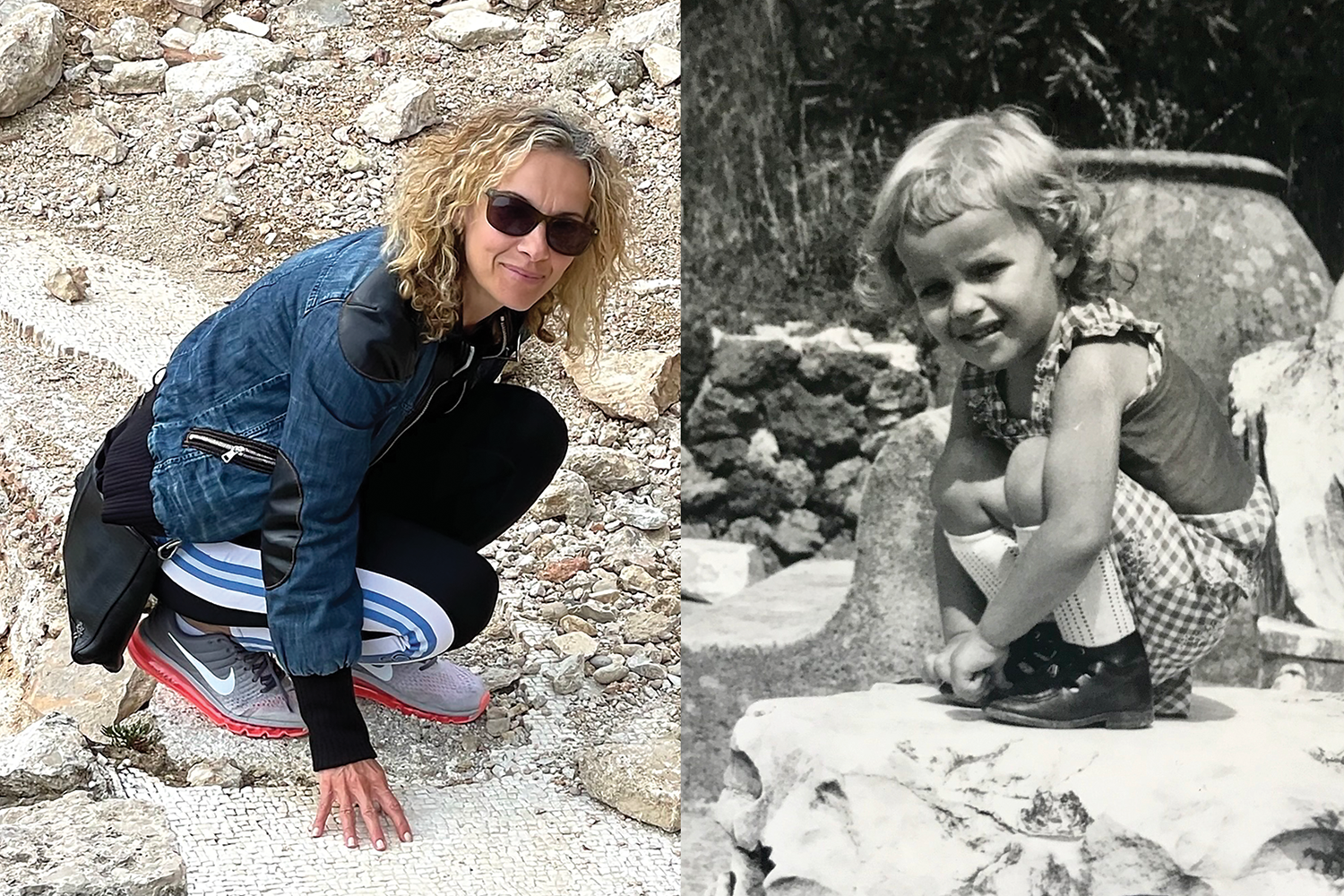

Matarazzo last year at Villa Formia, about 100 miles north of Naples, Italy, and, right, on a family trip in the late 1970s at the archaeological park of Cumae, about 12 miles west of Naples.

Know the Land on Which You Stand

Since completing her doctorate in anthropology at UConn, geoarchaeologist Tiziana Matarazzo has been unearthing the past to illuminate the present.

By Steve Neumann

Even by Italian standards, Tiziana Matarazzo '14 Ph.D. is exuberant as she talks about her work deciphering the remains of volcanic eruptions thousands of years ago. Her passion is so palpable, beaming through the small Zoom screen, it's almost like she's in the room. In fact, she's 4,000 miles away, sitting in the sunny environs of her home by the seaside in southern Italy.

Matarazzo, who was born in Naples between the shadows of two Âvolcanoes — Mount Vesuvius and the Campi Flegrei caldera — says she was inspired to do this brand of anthropological work because of her Âexperiences being a child in such a richly historical city. "I grew up in an ancient town, and every time I would walk to school, I would pass a Roman mausoleum; and every time I looked at the sea, I saw volcanoes."

After studying volcanology at the University of Naples Federico II, Matarazzo moved to the United States and enrolled at UConn, where she took a class called Old World Prehistory with the late UConn professor Robert Dewar. "After that, I just fell in love with archaeology — I was completely captured."

Geoarchaeologists like Matarazzo — who lives mainly in Italy but conducts all her research out of professor Natalie Munro's anthropology lab at UConn in the summers — apply geological methods to archaeological data to gain insight into how ancient human societies interacted with their environments. Matarazzo's specific area of expertise is micromorphology, a technique for examining small-scale structures and textures of sediment and rocks that are not visible to the naked eye, allowing for detailed observations crucial for interpreting the material's history and characteristics.

"Micromorphology can be used in different ways," she says. "You can learn about past climates and different types of volcanic eruptions, but it can also tell you what people were doing in different places."

Matarazzo's doctoral thesis focused on the early Bronze Age, an important transitional period for humanity that was characterized by emerging social complexity. Specifically, she investigated the impact of the eruption of Vesuvius in 1995 BCE, which was actually larger than the more famous one that destroyed Pompeii in 79 CE.

“That's what I really like about having a degree from UConn, because ... whether you're studying dirt, bones, or stones, if you're only very focused on your technique, you will not know the meaning of what you find.”

Her research used micromorphological analysis of thin sections of sediment collected at the village of Afragola — on the opposite side of Vesuvius as Pompeii — to understand how its people used living spaces, organized daily activities, and related to other members of the village. The site she studied contained a large number of well-preserved structures and materials, but her analysis revealed a general lack of human remains. "This is surprising," she says, "given the complexity of the site, as evidenced by multiple buildings utilized for storage and domestic activities — including the presence of large quantities of burned seeds; that suggests Afragola was an established agricultural village."

One explanation could be that the village was occupied only briefly before the Avellino eruption destroyed it. "They could see the eruption before it affected the village, so they just left. Afterward, the wind changed, and the ash came and covered the village."

This is different from what would happen a couple thousand years later at Pompeii, one of the most well-preserved catastrophes in human history. "The eruption of Vesuvius was preceded by numerous earthquakes years before the final eruption," Matarazzo says. "Because such tremors occurred frequently in this area, the people of Pompeii did not pay much attention. When Vesuvius erupted, some of them tried to leave, but most were trapped because there was a huge pyroclastic cloud that came down from the mountain at 200 kilometers per hour."

In addition to her more scholarly work, Matarazzo has written two archaeological guide books and is working on a third. One, "Curbside Roman Archaeology of Itri," was co-written with Anthony Philpotts, UConn professor emeritus of geology and geophysics.

Matarazzo says she is particularly passionate about a digital humanities project she has in mind for high school students at Liceo Scientifico Statale Enrico Fermi in her current town of Gaeta, Italy. "I want to focus on the archaeological sites during the Roman period in this little town," she says. "I want students to digitize all this information, because some of the sites were destroyed during World War II; consequently, some ancient constructions have been obscured by recent construction."

Though she started out researching the volcanic activity of the early Bronze Age of southern Italy after graduating from UConn, Matarazzo now studies the archaeology and anthropology of ancient Rome, in part to preserve and inform the local population about their cultural heritage.

"Because such tremors occurred frequently ... the people of Pompeii did not pay much attention."

"That's what I really like about having a degree from UConn," she says, "because in America, you have to have very good knowledge of anthropology to do archaeology — whether you're studying dirt, bones, or stones, if you're only very focused on your technique, you will not know the meaning of what you find."

Ultimately, Matarazzo wants to establish a type of honors program at the Liceo Scientifico school, where students can not only learn some archaeological techniques but also learn to be aware of the history that's literally in their backyard.

"I want people to know that this is important, because if you don't know where you're from, you can't know where you're going. And if people know their territory and their cultural heritage, they will learn to preserve it, too."

Above: The view from the top of the Old Town of Gaeta, where Matarazzo hopes to work with high school students.

UConn professor emeritus of geology and geophysics Anthony Philpotts and Matarazzo investigate a well-preserved stretch of the Appian Way in Itri, a small town near Rome, for their guidebook "Curbside Roman Archaeology of Itri."

Matarazzo collects micromorphological samples in Templeton, on a terrace of the Shepaug River in Washington, Connecticut. The Middle Paleo-Indian site is 11,190 years old.

Leave a Reply