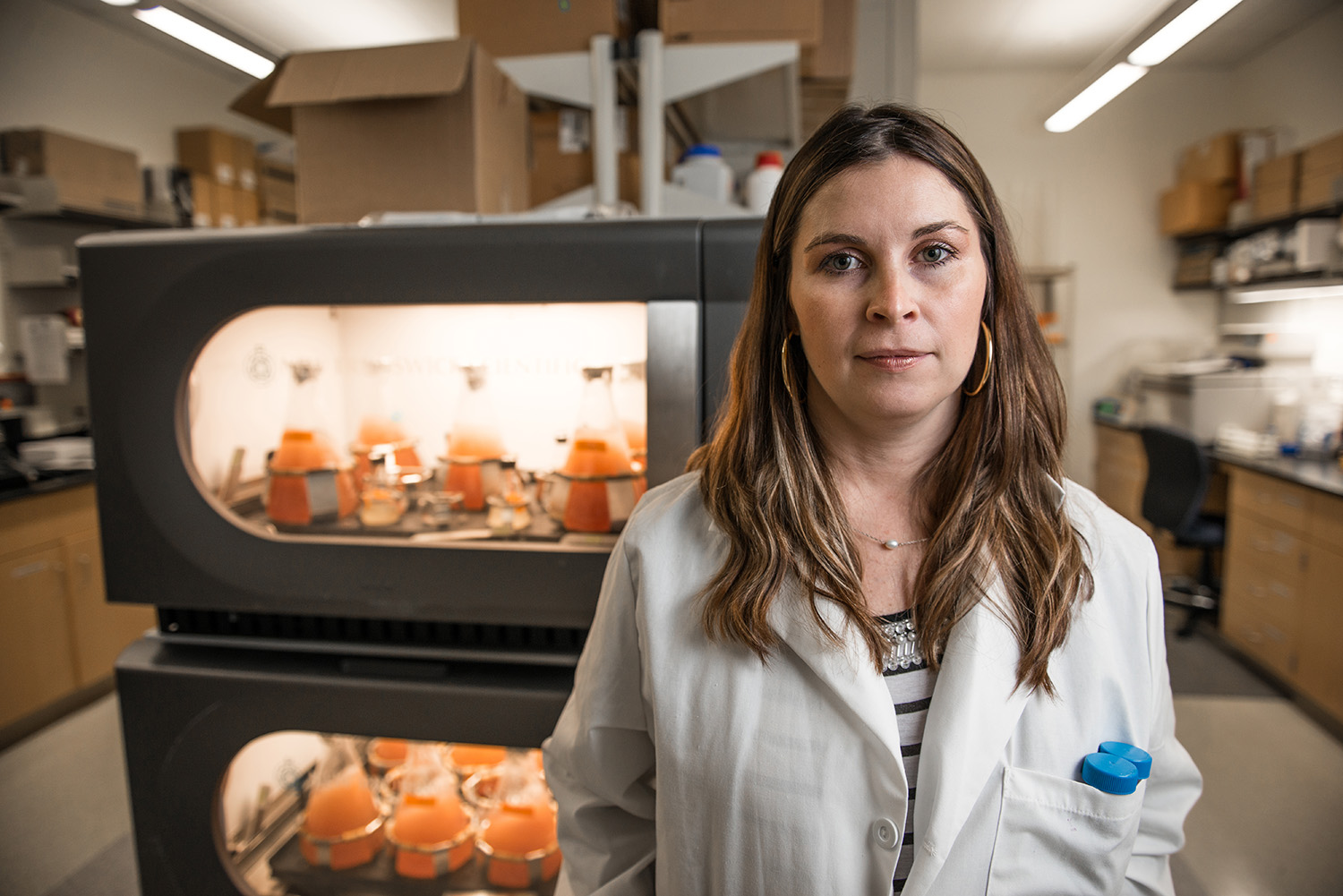

Nicole Wagner Wants to Help People Regain Vision

Sending artificial retinas into space may be the breakthrough she needs

Wagner works to cure degenerative retinal diseases at her Farmington, Connecticut, lab that is part of TIP, UConn's Technology Incubation Program.

The first time Nicole Wagner '07 (CLAS), '13 Ph.D. saw a rocket launch she couldn't help but feel a little starstruck. It was a balmy December day at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, and that afternoon a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket was scheduled to depart on a mission to the International Space Station. As a SpaceX VIP, Wagner had received a personal tour of the center and now had one of the best seats in the house to watch the launch, where she was surrounded by the astronauts who would one day hitch a ride to space on the company's flagship rocket.

The rocket Wagner had come to see, however, wasn't carrying humans. It was loaded with supplies and a trunk full of cutting-edge experiments, including one built by Wagner's company, LambdaVision, and its implementation partner, Space Tango. The shoebox-sized container was filled with bags of bright purple fluid designed to grow artificial retinas in microgravity without the need for human intervention.

The experiment may have been small, but it was an important proof of concept that Wagner hoped would lay the foundation for an entirely new approach to manufacturing artificial retinas. If she was right, it would be the first small step toward a solution that could provide relief to the millions of people living with degenerative retinal diseases back on Earth.

These are progressive diseases that ultimately lead to blindness. People who experience them can have difficulty with everyday activities like driving a car or reading a book. And while there's no cure, patients can regain some vision by swapping their decaying retinas for implants. The problem is that most retinal implants are electronic and come with a litany of technical challenges including a tendency to overheat.

In 2009, Wagner co-founded LambdaVision with UConn professor emeritus Robert Birge to commercialize the organic approach to producing artificial retinas that Birge had pioneered in his lab. Unlike electronic retinal implants, LambdaVision's artificial retina is composed of a photosensitive protein called bacteriorhodopsin that replaces rods and cones damaged from retinal degenerative disorders.

"Let's do this — let's build a microgravity experiment."

To create their protein-based artificial retina, Wagner and Birge have spent the past decade perfecting a laborious process that grows ultrathin layers of protein on a substrate while it's suspended in a solution — and then painstakingly stacking hundreds of these protein layers to create an artificial retina.

The challenge with this approach is that each of the hundreds of protein layers needs to be almost perfectly uniform. Even a small imperfection in a single layer can spoil the entire artificial retina, but the effects of gravity — which impacts the evaporation rate, influences surface tension, and can lead to sedimentation of solutions — make ensuring this uniformity across layers an immense challenge.

If these retinas were to be manufactured in space, however, it could enable the mass production of nearly perfect artificial protein-based retinas by taking gravity out of the equation.

Wagner admits that manufacturing LambdaVision's artificial retinas in space wasn't an option she had considered until a chance meeting with representatives from the International Space Station Laboratory in 2016.

"I went to the meeting really not knowing what to expect," she says. "But they had a funding opportunity for in-space manufacturing and we needed the money. So Dr. Birge and I said let's do this — let's build a microgravity experiment."

Wagner and the LambdaVision team soon secured NASA funding for that first in-space experiment, which launched to the ISS on a SpaceX rocket in late 2018. Since then, the company has flown seven experiments to the space station with an eighth scheduled for later this summer.

Although Wagner never set out to build a low-Earth-orbit biotechnology company, the results from the experiments have buoyed her conviction that in-space manufacturing may be the key to getting LambdaVision's artificial retinas into the eyes of the millions of patients who stand to benefit from them. Her team has successfully managed to create many 200-layer retinas in microgravity while demonstrating that it can adhere to the same types of strict manufacturing protocols in space that biotech companies are held to on Earth. And while the space shots have become somewhat routine for the company, Wagner still savors the thrill of bidding a bon voyage to her technologies alongside an audience of astronauts.

"I'm still starstruck by astronauts every time I meet them at NASA," she says. "I don't know if that'll ever wear off because it's just so cool."

By Daniel Oberhaus

Photo by Nathan Oldham

Leave a Reply