G-Man

Frank Figliuzzi's FBI Story

By Peter Nelson

T

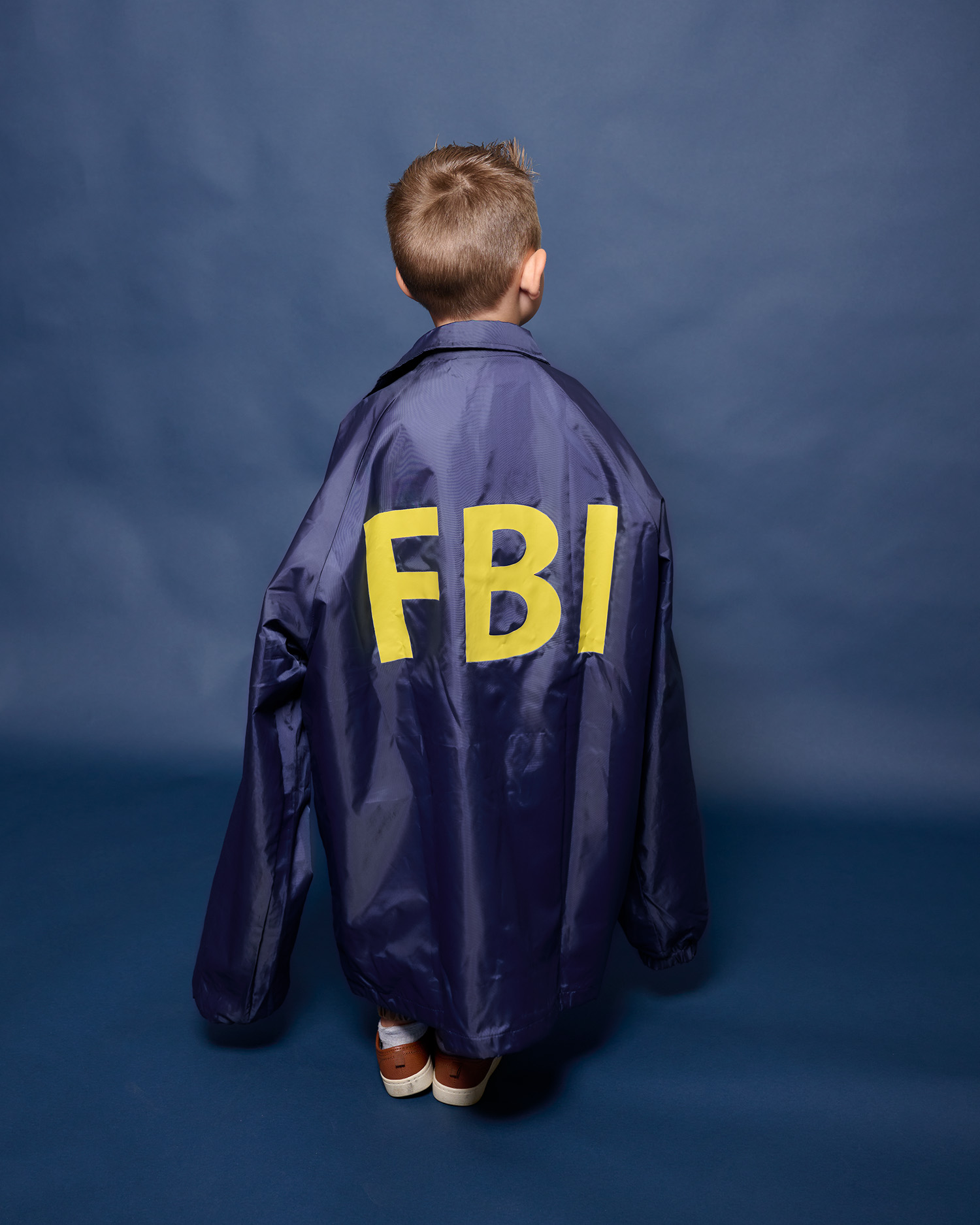

he first time Frank Figliuzzi '87 JD applied to be an FBI agent, he was turned down.

He was disappointed — but then again, he was only 11 years old.

"I loved the old Sunday night TV show 'The FBI' with Efrem Zimbalist Jr.," says Figliuzzi. "These guys would solve every problem in the world in less than an hour — and they wore suits."

The first time Frank Figliuzzi '87 JD applied to be an FBI agent, he was turned down.

He was disappointed — but then again, he was only 11 years old.

"I loved the old Sunday night TV show 'The FBI' with Efrem Zimbalist Jr.," says Figliuzzi. "These guys would solve every problem in the world in less than an hour — and they wore suits."

When Figliuzzi was two, his father moved the family from Port Chester, New York, where he'd owned a small Italian foods shop, to New Fairfield, Connecticut, to become a regional manager for ShopWell foods. Young Frank loved the idyllic suburbs, but found the city more exciting.

"As a kid growing up in southern Connecticut, our news came from the New York media market, stories of the FBI breaking up the mafia. These guys using their brains for justice and equality." Inspired, he wrote a letter to the New Haven field office, asking the head of the FBI in Connecticut for a job. "The guy wrote me back and said, 'Here's what you need to do — get back to us in about 15 years.'"

Figliuzzi's career plan, never waverÂing, was met with all manner of skepticism along the way. An uncle told him at a family gathering, "I don't think it's gonna work, because we're Italian, and I don't think they like us." Undaunted, he gained a bachelor of arts in English from Fairfield University in 1984, the first in his family to earn a college degree, and went on to get his law degree, with honors, from UConn in 1987. He knew a law degree would be attractive to FBI recruiters but says his classmates scoffed.

"They looked at me like I was crazy. 'You're gonna live on a government salary?' They were all trying to become a partner in some law firm. Within a couple of years, those same classmates were calling me, saying they couldn't stand the lack of integrity at their law firm, or they were bored out of their minds, and how could they get an application to the FBI?"

Integrity has always mattered to Figliuzzi, who became an agent almost exactly 15 years after writing that letter and the same year he got that law degree. He worked in Atlanta, San Francisco, Silicon Valley, and at FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C., where he was a unit chief in the Office of Professional Responsibility, the FBI's Internal Affairs component. In 2001, after the 9/11 attacks, he headed the Joint Terrorism Task Force in Miami, where many of the attackers had trained, and where the government feared more were hiding.

A week after 9/11, anthrax powder was discovered in the Boca Raton mailroom of American Media, publisher of the National Enquirer. Al Qaeda was suspected at first, though the search ultimately led to a home-grown government scientist. Figliuzzi directed the FBI investigation from a trailer in the parking lot outside the American Media offices.

"It's a 60,000-square-foot, three-Âstory building, filled with microscopic, deadly anthrax spores that killed somebody, and we're doing hazmat entries into the building. Meanwhile, I see kids getting on school buses. I see people out for their morning run, oblivious to the fact that down the street, an incredibly deadly attack has occurred. But that's why we have the FBI, to take that kind of burden on, so that everybody else doesn't have to worry about it."

That sense of mission and honorable purpose has animated Figliuzzi's life from the first day he set foot in the FBI Training Academy in Quantico, Virginia. After Miami, he became Chief Inspector and led the Cleveland Division in 2004. In 2011, he was named Assistant Director of the Counterintelligence Division, the nation's top spy-catching agency. Over his 25 years of service, he watched the FBI change from an organization that primarily investigated crimes after the fact to one that tried to predict and prevent them.

"Leading up to 9/11, the entire U.S. intelligence community was aware, because of the chatter being picked up by agencies across the globe, that people were being moved," says Figliuzzi. "There was talk of assets being in place, waiting for the signal. We knew it was going to be big, but not where or how."

After the 9/11 intelligence failure, the FBI hired thousands of young analysts to sift through all the data being collected and received.

"That was a huge strategic shift," says Figliuzzi. "You can imagine seasoned, grizzled FBI agents with guns and badges, and now we have young analysts embedded on every squad, in every office, who are suddenly driving cases, connecting the dots. I'm not sure I would get into the FBI today. Advanced degrees are now the norm for FBI agents. Today's recruiting needs are hard sciences. Biochem for work in theft of trade secret formulas. Foreign languages, people who are fluent in Urdu and Farsi. People with national security intelligence experience. People with military experience. Wall Street finance experience for white collar crime. And, of course, cybersecurity is huge."

Cyber has driven what Figliuzzi sees as another fundamental shift in what threatens us. It comes both in the way social media can radicalize and organize domestic terrorists like those who attacked the Capitol on Jan. 6 and in the way foreign actors can shut down, or hold ransom, American infrastructure like the Colonial Pipeline or the JBS meat-packing plant.

"This is the future. That's how the next war starts," he says. "We might already be in it."

Figliuzzi perceives another shift in the bureau, one that is potentially even more critical. The FBI has a long tradition of policing itself and keeping its house in order, from vetting new recruits to polygraphing agents to debriefing missions in order to understand what mistakes were made. Outsider attacks undermine the agency's reputation, even if they prove to be untrue.

The FBI, traditionally seen as a straitlaced apolitical law enforcement agency, has in recent years found itself at the center of multiple high-profile political controversies. From the investigations into former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton's email use and into potential ties between Russia and Donald Trump's 2016 presidential campaign to the recent search of Trump's home in Florida to retrieve top secret government documents, the agency has received a mixture of withering criticism and high praise from both ends of the political spectrum in an increasingly polarized America. In one of the most explosive events in the agency's history, FBI Director James Comey was publicly fired in 2017. The reason cited at the time — which was highly disputed — was his handling of the Clinton email investigation.

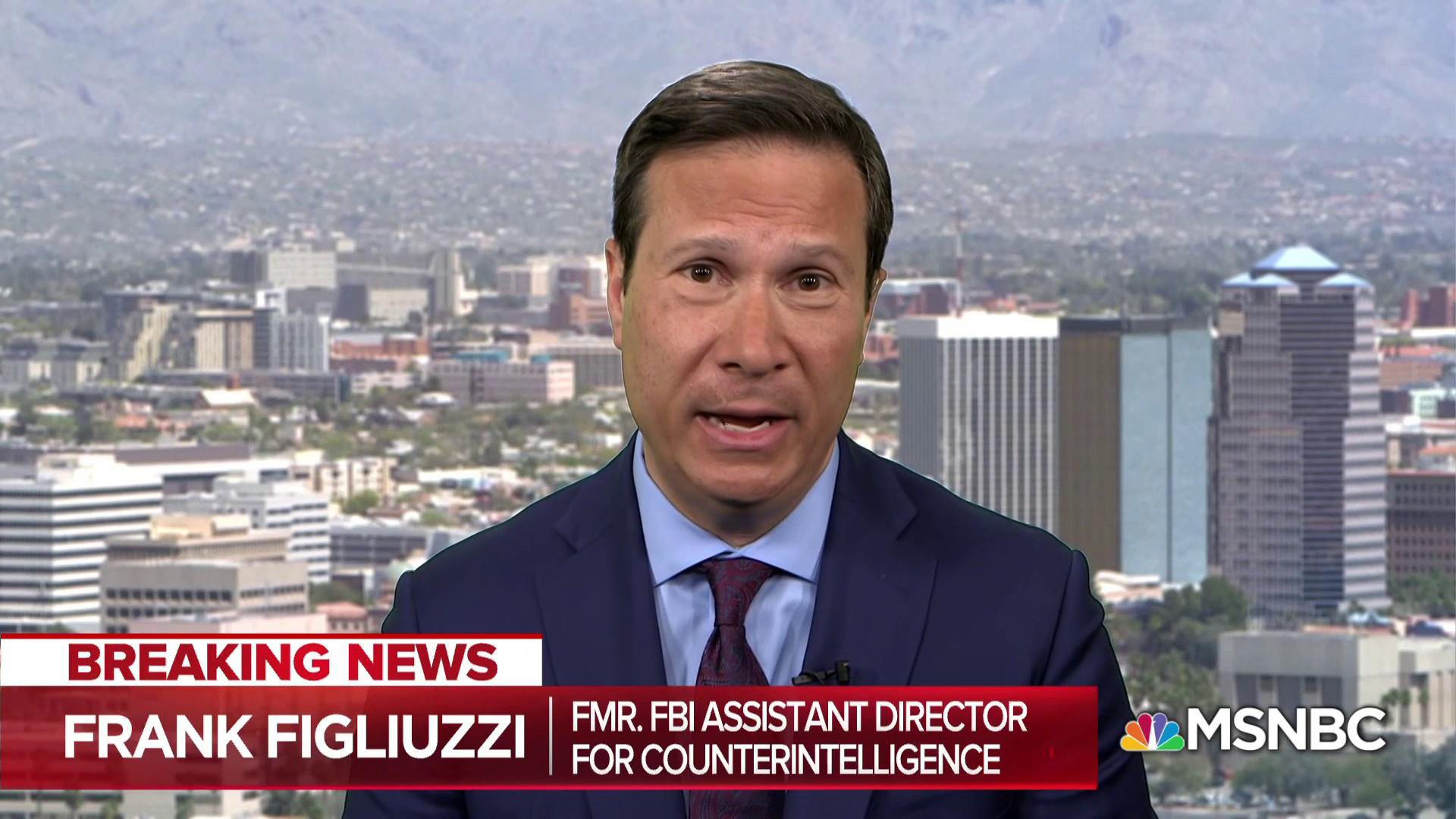

For Figliuzzi retirement means living in Tucson, Arizona, working as an analyst for MSNBC, publishing a book, and hosting a podcast — "The Bureau with Frank Figliuzzi."

To avoid the appearance of partiality and to be transparent, said Comey, he famously closed, reopened, then again closed an investigation into then presidential candidate Hillary Clinton's emails, prior to the 2016 election.

"Comey is a man of incredible integrity and ethics and yet, in his very attempt to do the right thing, he ended up having the exact opposite impact," Figliuzzi says. You don't have to be atop the organization for the burden to be immense, consequential.

"When young people talk to me about a career in the FBI, I say look, this is not a career or another job. It's a calling. You're never off duty. At a backyard barbecue or a kid's PTA meeting, you're that FBI person. You blow off vacations, birthdays, anniversaries, kids' games. You look at your watch at five p.m., but the bad guys don't stop at five. There's a constant sense of urgency and of gravity. You make what could be literally life and death decisions, seven days a week, weeks on end."

The FBI recognizes the stress that comes with the job, and the burnout that sometimes accompanies it, and allows federal agents to retire with 25 years of service — for Figliuzzi that came in 2012. "The good news is, you get to retire young," he says. "The bad news is, you usually do need to retire when that time comes."

For Figliuzzi, retirement has not been laid back. Last year he published "The FBI Way: Inside the Bureau's Code of Excellence," which is, among other things, a call for empathy, a path to recovery. In an era where every certainty is called into doubt, every bit of news you disagree with is "fake," and every investigation is "a witch hunt" or a "hoax," Figliuzzi believes a return to the FBI way is both timely and crucial. The FBI was once considered one of the most trustworthy government agencies in the country, if not the world. Figliuzzi hopes it can be that again.

"When you bash the FBI so much that you demoralize the men and women who work there, you degrade their mission, and then, when an FBI agent knocks on a citizen's door and shows credentials, that citizen has to pause for a minute and wonder whether they can trust that FBI brand. Then we've got a big problem. That's really what compelled me to write this book."

Figliuzzi also has become a frequent contributor on MSNBC and he hosts a podcast, "The Bureau with Frank Figliuzzi," in which he interviews current active-duty FBI agents. He attributes his gift for eloquent speaking in part to his schooling at UConn Law.

"Success is about effective communication. If you can't communicate your ideas effectively, you're not going to get anywhere. One of the strong things about UConn was, they stopped you from talking or writing like traditional lawyers. Lawyers have had a reputation for really laborious, circuitous language. UConn really didn't stand for that. I credit a great deal of my success in my career to them."

Leave a Reply