Betrayal

"I love the hunt," says alum Rosemary Sullivan, a queen of compelling biography, whose latest tome tackles one of World War II's most persistent and villainous mysteries.

By Julia M. Klein

Illustration by Christa Yung

R

osemary Sullivan '69 MA was a 12-year-old schoolgirl in Quebec, Canada, when she first read "The Diary of Anne Frank."

"It seemed just Âotherworldly that somebody would be trapped in a house for two years without being able to look out the window or make any noise," she recalls. Rereading the diary as an adult, familiar with the wartime context, "changed my relationship with Anne Frank," she says. "I was deeply impressed by the intelligence and candor and the moments of satire. It was an astonishing performance for a child from the age of 13 to 15."

Rosemary Sullivan '69 MA was a 12-year-old schoolgirl in Quebec, Canada, when she first read "The Diary of Anne Frank."

"It seemed just Âotherworldly that somebody would be trapped in a house for two years without being able to look out the window or make any noise," she recalls. Rereading the diary as an adult, familiar with the wartime context, "changed my relationship with Anne Frank," she says. "I was deeply impressed by the intelligence and candor and the moments of satire. It was an astonishing performance for a child from the age of 13 to 15."

Her re-encounter was a prerequisite to a project that has captured headlines — and stimulated controversy — around the world this year. "The Betrayal of Anne Frank" (HarperCollins) is Sullivan's meticulous account of a 5-year-long cold case investigation into a longstanding mystery: how Anne Frank, her family, and four other Jews hiding in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam came to be arrested and deported. (Of the eight, only Anne's father, Otto Frank, would survive the war.)

The investigation, featured on CBS's "60 Minutes," identified a surprising culprit: Arnold van den Bergh, a prominent Jewish notary desperate to save his own family. New York Times reviewer Alexandra Jacobs found the argument for his culpability "convincing, if not conclusive." The reaction abroad — at least from those countries with the greatest stake in the story — was less favorable. In response to a critical report by five Dutch historians, the Dutch publisher, Ambo Anthos, announced in March that it would cease publication and remove the title from bookstores. HarperCollins Germany delayed the book but plans to publish a revised version later this year.

"I never doubted, and I still don't doubt, the integrity of the investigation," Sullivan says, noting that her larger goal was to describe the context of the tragedy. While tracing the investigation's labyrinthine twists, she paints a portrait of World War II Amsterdam as a site of scarcity, peril, and shifting political allegiances. Death shadowed the entire Dutch civilian population, but especially the country's Jews, most of whom died in Nazi concentration camps. "It should be possible to understand that van den Bergh was as much a victim as anybody else," Sullivan says.

The Biographer as Detective and Adventurer

This Anne Frank project was a departure for the 74-year-old poet turned biographer. An emerita English professor at the University of Toronto, Sullivan had authored 14 previous books, including 2015's acclaimed "Stalin's Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva" and "Villa Air-Bel: World War II, Escape, and a House in Marseille." She revels in tracking down archival documents and finding interview subjects in far-flung places. "I love the hunt," she says. "The subtext of biography is as exciting as the text. The adventure, the search for the subject, involves encounters with people, geographies, political contexts. It's a very enlarging experience."

For this recent book, the parameters were more defined. An interdisciplinary team, relying on techniques such as artificial intelligence, crowdsourcing, and criminal profiling, conducted the research. Sullivan's contribution was "an act of synthesis, pulling it all together," she says, something at which she has long experience. Still, little in her early life predicted that she would become the narrator of such an iconic Holocaust story. "I didn't expect this to be my trajectory," she admits.

"an embedded journalist"

Born into an Irish Catholic family outside Montreal, she was the second of five children. Her mother's forebears immigrated after losing a child to the Irish potato famine of the 1840s; according to family lore, her father's father was a revolutionary who fled after the 1916 Easter Uprising. Rosemary's mother, Leanore, whose father was a Canadian cycling champion, met Rosemary's father, Michael Patrick Sullivan, Quebec's 1935 Junior Middleweight Boxing Champion, on a blind date.

"Growing up in Quebec, you have to have a sense of politics — or be aware of how power functions," Sullivan says. She "fell in love with books in high school," but her father wanted her to help support the family. At his urging, her high school principal counseled her that "university would be wasted on a woman." She ignored them both and attended McGill University with the help of a Rotary Club scholarship.

Sullivan followed the advice of one of her McGill professors, who suggested she get degrees from three different countries. Her master's in English literature came from UConn, her doctorate from the University of Sussex in England. During her time at UConn, the poet Stephen Spender was a writer-in-residence, and Sullivan met Spender's longtime friend W.H. Auden, who was visiting. In 1986, she would win an award for best first book of poetry in Canada for her own collection, "The Space a Name Makes."

Sullivan's first book, adapted from her doctoral thesis, was "The Garden Master: The Poetry of Theodore Roethke." But she would specialize in chronicling the lives of literary women.

Of Poets, Oligarchs, Revolutionaries — and Margaret Atwood

In 1979 Sullivan traveled to Czechoslovakia and the Soviet Union, where she met dissident writers. Her glimpses of those closed societies eventually became valuable background for "Stalin's Daughter," and the trip inspired her to join Amnesty International and found the Toronto Arts Group for Human Rights. In 1981, she organized an international congress in Toronto to generate support for politically endangered writers, which attracted such literary stars as Susan Sontag, Allen Ginsberg, South Africa's Nadine Gordimer, Argentina's Jacobo Timerman, and the Soviet dissident poet Joseph Brodsky.

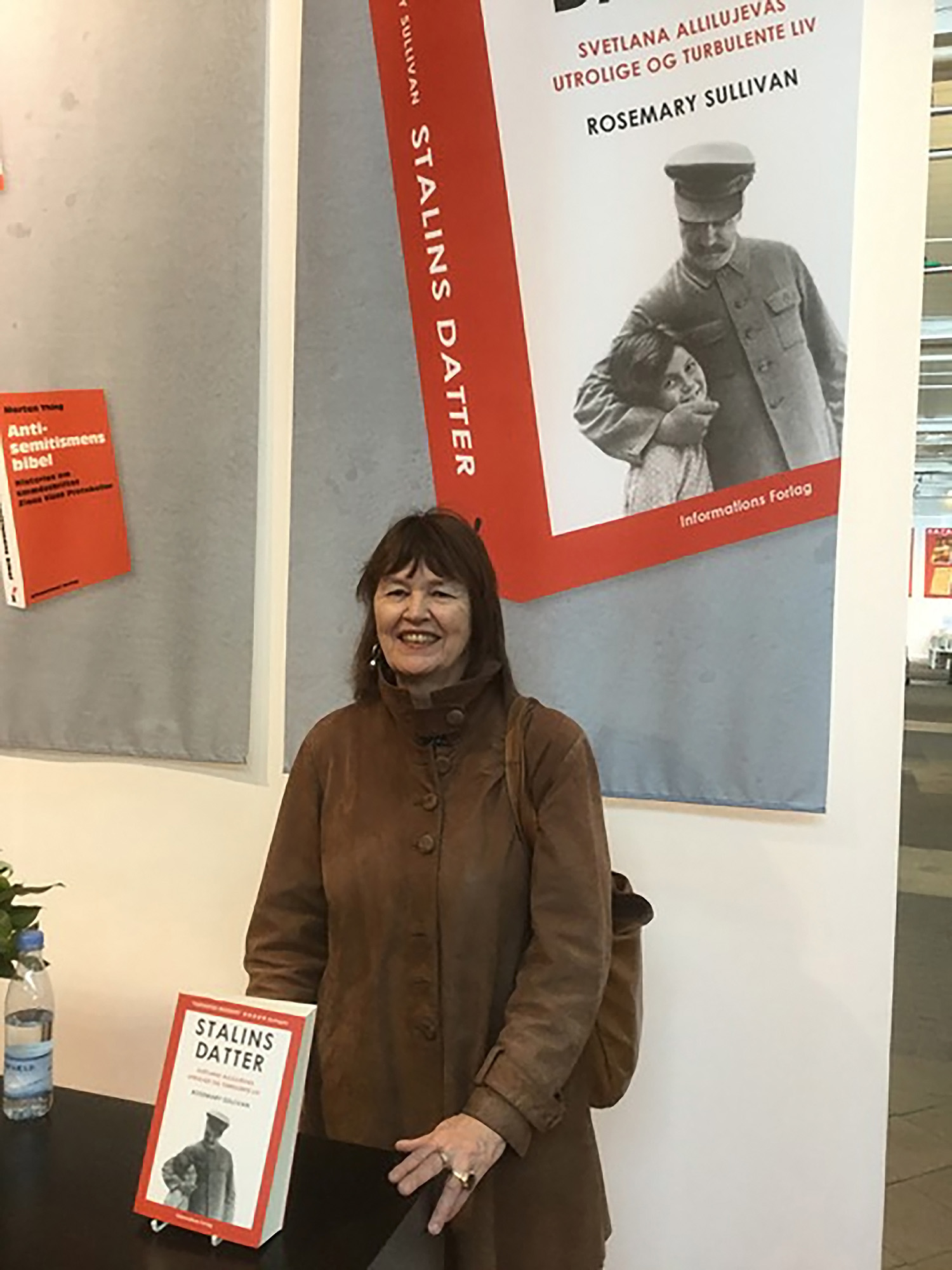

Sullivan at a book fair in Denmark promoting her acclaimed "Stalin's Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva."

A conference volunteer who became an editor later invited her to write a biography of Elizabeth Smart, a Canadian poet and novelist who had been a friend of Sullivan's. After "By Heart: Elizabeth Smart/A Life" (1991), Sullivan published "Shadow Maker: The Life of Gwendolyn MacEwen" (1995), on another Canadian writer, and "The Red Shoes: Margaret Atwood Starting Out" (1998). Atwood, arguably Canada's best-known novelist, was not initially keen on cooperating on a biography — "I'm not dead," she said — but Sullivan proved persuasive.

Then the 2001 film "Varian's War" sparked Sullivan's interest in American Holocaust rescuer Varian Fry. Fry had been the subject of a recent biography, so Sullivan took a different tack. She focused on a chateau outside Marseille that became a refuge for intellectuals and artists assisted by Fry. Published in 2006, "Villa Air-Bel" won the ÂCanadian Society for Yad Vashem Award in Holocaust History and marked her first immersion in what Sullivan calls "the most important narrative of the 20th century." She and her husband, the Chilean musician and sound engineer Juan Opitz, also collaborated on a short film about the villa.

A casual conversation with her then-editor at HarperCollins, Claire Wachtel, in 2011, inspired "Stalin's Daughter." An obituary of Svetlana Alliluyeva had just run in The New York Times, and Wachtel told Sullivan, "You should write that biography." Sullivan protested that she didn't speak Russian, but Wachtel insisted that might be an advantage: "It won't be one of those scholarly things."

Russian-speaking research assistants helped Sullivan sort through archival treasures, including Alliluyeva's poignant childhood letters to her tyrannical father. And the cooperation of many friends and relatives, especially Alliluyeva's daughter Olga, allowed Sullivan to invest her story of a tragic, peripatetic, intermittently literary life with a rare intimacy. She recalls Olga telling her, "There were moments when my mother would be totally broken, and you would see her in the night terrors of a child, and there was nothing you could do to console her."

The research took Sullivan to Moscow, St. Petersburg, Georgia's capital of Tbilisi, London, England's Lake District, and Frank Lloyd Wright's Taliesin West in Arizona. "It was thrilling," she says. Published in 23 countries, "Stalin's Daughter" won critical plaudits and a passel of prizes, including the Biographers International Organization Plutarch Award. But Sullivan derives special satisfaction from Olga's reaction: "You were on my mother's side."

A Divided Citizenry, a Complicated Villain

When Sullivan got a call from her agent in November 2018, telling her that HarperCollins wanted her for the Anne Frank project, she didn't sign on right away. She wanted to be sure. She reread the diary and dove into biographies of Anne Frank and her father, Otto, before deciding, "This is a really remarkable subject."

Two Dutch investigations of the betrayal, in 1947"“48 and 1963"“64, focused on Willem van Maaren, who worked in the warehouse beneath the Franks' hiding place and stole from the business. Both were inconclusive. The new investigation was the brainchild of Dutch filmmaker Thijs Bayens, whose grandparents had hidden Jews during World War II, and Dutch journalist Pieter van Twisk. They, in turn, hired Vincent Pankoke, a retired FBI special agent who had previously targeted Colombian drug lords and Wall Street corruption, to oversee the ambitious project. The HarperCollins advance helped fund the undertaking.

Sullivan flew to Amsterdam in May 2019 to spend a month with the cold-case team and visit key sites, including the Anne Frank House. Pankoke says she "acted like an embedded journalist witnessing and experiencing our every move and emotion" and was especially "fascinated by the emotional details of the time." Sullivan's planned return to Amsterdam in early 2020 was short-circuited by the pandemic, but the internet and video conferencing kept her abreast of the investigation.

"The Betrayal of Anne Frank" begins with a background section on the Frank family. It then thumbnails several suspects, including van Maaren; Nelly Voskuijl, the Nazi-infatuated sister of a Dutch woman who helped hide the Frank family; and Anna "Ans" van Dijk, a Dutch Jew executed after the war for informing on other Jews. The point "wasn't just to find who betrayed Anne Frank," Sullivan says. "It was to give an impression of what it was like to live under occupation, in constant fear. And to ask for moral clarity in such a context is absolutely arrogant."

Van den Bergh's name first surfaced in an anonymous note sent after the war to Otto Frank. Frank later copied the note and gave it to the second Dutch investigation. The cold-case team surmised that Frank came to believe in van den Bergh's guilt, but kept mum for fear of stirring up European anti-Semitism. "That put us, as author and cold-case investigative team, in a difficult position," says Sullivan. "Do we say something that Otto Frank didn't?"

The notary's story is "really complex and interesting," she says. Once prosperous and respected, he lost almost everything — his profession, his home, his security. His children were in hiding, and he and his wife were on the run. A member of Amsterdam's Jewish Council, with connections to both high-ranking Nazis and the resistance, he may have viewed his best option as trading information.

"Like Otto Frank's, his goal was simple: to save his family," Sullivan writes. "That he succeeded while Otto failed is a terrible fact of history."

After the book's publication and an initial burst of favorable publicity, a story in The New York Times showcased the skepticism of Dutch scholars, some of whom questioned whether the

notary could have possessed the addresses of Jews in hiding. The Dutch publisher beat an immediate retreat.

"I was shocked," Sullivan says. "The response — 'We apologize to anyone who feels offended by this book' — is such a capitulation to the ideological divisiveness of our time." Sullivan's recent books chronicle just such "periods of enormous ideological division, which often lead to violence," she says. "We're in a very risky period. We're living in these separate towers where we can't talk to each other. We're really going to have to be very careful, because something rather nasty is surfacing."

At the moment, Sullivan is working on a collection of her travelogues, dating back to 1977 and including solo trips to the Soviet Union, Czechoslovakia, India, Egypt, Cuba, Peru, Mexico, Chile, and the Great Bear Rainforest in British Columbia, among other places.

"I returned to reading them, provoked by the lockdowns during the pandemic," she says. She plans to thread the pieces with autobiographical meditations: "What in my childhood made me a lonely traveler? What did I learn from my travels? What will traveling be in the future?"

As usual, she says, "I'm enjoying the writing."

Nice article. Just was curious about the author’s comment of not being able to look outdoors for 2 years.

There is a tree by their old hide out and about 10 years ago or so, Anne Frank enthusiasts were trying to save the tree because–on my re read a few years ago–Anne Frank, the definitive edition, Anne looks out at a tree and wonders on paper aloud.

Anne Frank enthusiasts tried to save the tree since the tree itself, made the diary.

So I wonder on the inaccuracy of the observations of–not seeing outdoors for 2 years… as it was apparent she saw the sky and the tree alike.

Tony, class of 2000.

When Tony Mac is able to read The Betrayal of Anne Frank: A Cold Case Investigation, he will see that several mentions are made of Anne Frank looking out a window. She would occasionally sneak down to the Opekta front office to hide behind the curtains to peek outside—on one occasion she saw a file of desperate Jews being herded down the street by Nazis. She, Peter van Pels, and sometimes Margot would sit at the attic window upstairs from where they could see her tree which she writes about so eloquently. The annex residents had to be careful never to be seen—they could not open a window and stick there heads out to breathe the fresh air. They were actually never “out of doors†and their vision out the window was always restricted.

All best, Rosemary Sullivan

This seems unnecessarily vindictive.

The author’s rebuttal of the severe criticism by Dutch scholars of the quality of the research the Anne Frank book is based on, is ridiculous. The entire book is a disgrace to history as an academic discipline in general and to Holocaust research in particular: most assumptions are wrong and not founded in primary sources. It is with very good reasons that this book was revoked from European bookshop shelves. This has nothing to do with the so-called polarization in society or with ‘ideological division’ but everything with the defense of decent, scholarly research, which this book is not the product of.

Know the truth and the truth shall set you free.

Who are we to judge Van den Bherg?

Who knows what we would trade to save his family?