Soldiers of the Sandinista Popular Army forcibly evacuating peasants during period of intense fighting with Contra rebels in El Ventarrón, Nicaragua, 1985.

For Scott Wallace, Remote Learning Means Getting Off the Beaten Path

The photographer and National Geographic contributor shares with us some of the hard-won wisdom he imparts to UConn's lucky journalism students.

By Lisa Stiepock

Photos by Scott Wallace

M

ost kids who spent childhoods thumbing through the pages of the canary-yellow-framed National Geographics on their coffee tables, marveling at titular photos of exotic people and places, only imagined a day when they'd travel the world and see their own names attached to such stories and photos. Scott Wallace made it happen. Actively into his fifth decade of reporting, writing, and shooting stills and video for not just National Geographic but Smithsonian, Travel & Leisure, Harpers, and the like, the journalism professor illustrates his trade secrets and advice to students with real-life narratives that sound straight out of a big-screen blockbuster — one in which the pursuit of truth and justice is filled with as much trauma as triumph.

Most kids who spent childhoods thumbing through the pages of the canary-yellow-framed National Geographics on their coffee tables, marveling at titular photos of exotic people and places, only imagined a day when they'd travel the world and see their own names attached to such stories and photos. Scott Wallace made it happen. Actively into his fifth decade of reporting, writing, and shooting stills and video for not just National Geographic but Smithsonian, Travel & Leisure, Harpers, and the like, the journalism professor illustrates his trade secrets and advice to students with real-life narratives that sound straight out of a big-screen blockbuster — one in which the pursuit of truth and justice is filled with as much trauma as triumph

Scott Wallace interviewing an officer from the Sandinista Popular Army in Nueva Segovia, Nicaragua, 1984. Photo by Bill Gentile

Telling us how he uses these exploits to illustrate the tenets he most wants to impart to his students, Wallace checks himself. "I don't want to spend a lot of time talking about my own career, but I think I do have a rich trove of experiences to draw on."

It's an understatement. Wallace has traveled on assignment to the remotest of remote places on Earth and had a career most storytellers and adventurers only dream of. His recantations arrive humbly, however, with thoughtful pauses, counterquestions, and intellectual insights that serve to remind he's usually on the other side of the interview.

"Everybody has a story worth telling, and our job as journalists is to pull it out of them," he says while clicking through a computer slide show of favorite photos. His Oak Hall office brims with memorabilia, maps, magazines, and framed photos, including a prominent three — each of his grown sons. Wallace has an open, friendly demeanor made even less threatening by the slightly scruffy grooming one imagines is not just a pandemic thing. It's hard to conjure a more inspiring teacher, or one with more entertaining, hard-won, and wise advice to impart.

Don't Stop for Every Body in the Road

For starters — literally — there's this predicament from his first day as a professional reporter in 1983, just weeks out of J school and having made his way to civil-war-torn El Salvador with $50 in his pocket and a no-certain-paycheck "job" stringing for CBS News. On the way to Wallace's crash pad, his driver swerves around a body in the road. Wallace suggests they should stop to help. "You don't know who that person might be or why he is there," says the driver, who does call for help when they reach their nearby destination. Wallace chalks it up as "my first lesson in how to survive in a war zone."

The Truth Is on the Ground, Not on the Web

Exploring El Salvador and, later, Nicaragua and Guatemala, Wallace felt almost immediately not just the risk of what he was doing but the weight of it. It was clear that reports from him and his colleagues were the only counter to rivers of propaganda from Central American and U.S. governments. It was also clear that to find the truth he had to get out of the cities into the countryside, "where the heart and soul is." He and a Newsweek photographer ventured deep into said countryside on one foray and, having bamboozled their way past army checkpoints, found themselves witnessing a battle in which two Contras fought to the death against a far greater number of Sandinistas. Why would they do that, wondered Wallace, if they were, as the Sandinistas insisted, mercenaries paid by the U.S.?

"Firsthand experience is always the best way to distinguish between information and its opposite," says Wallace. You naturally form opinions, but be ready to change those opinions in the face of facts gathered on the ground.

CENTRAL AMERICA: Key to documenting civil war here in the '80s was getting deep into the countryside and speaking fluent Spanish.

Mothers and children march against death squads and kidnappings of their loved ones in San Salvador, El Salvador, 1983.

Leftist rebels enter the city of Chinameca, El Salvador, aboard a pickup, 1983.

A double rainbow on the road to Nicaragua's remote Atlantic Coast, 1986.

Adolescent guerrilla in Usulután Province, El Salvador, 1989.

Know the Risks, Embrace the Friendships

There are moments when reality is all too real. "It was in El Salvador in '89, Election Day," recalls Wallace. "Some friends and I enter a village where there has just been combat.

The guerrillas have taken over, and we are interviewing these kids with rifles, asking them, 'What are you doing? There was supposed to be a ceasefire today.' And then the army counterattacks. One of my friends is hit by a sniper bullet. He looks at me and I see the life go out of his eyes and he goes down. It was terrifying. I thought we were all going to die. I had no idea how we'd get out of there." The rest of them did get out, and that type of shared experience and mission forges deep bonds, says Wallace. "The friends I made early on in Central America are still among my very best friends. There's a camaraderie and solidarity in doing this kind of work. It is understood that everyone is taking a risk — I'm not talking about physical risk, though there is that too, yes, but about being willing to risk failure. In the conventional sense. There won't be 401(k)s and you'll have to wait for things like marriage and kids. And even then, well, trips come up, vacations get canceled."

Nicolas Reynard, Scott Wallace, and Matis indigenous scouts, Javari Valley Indigenous Territory, Brazil 2002.

Keep a Bag Packed and Your Passport Current

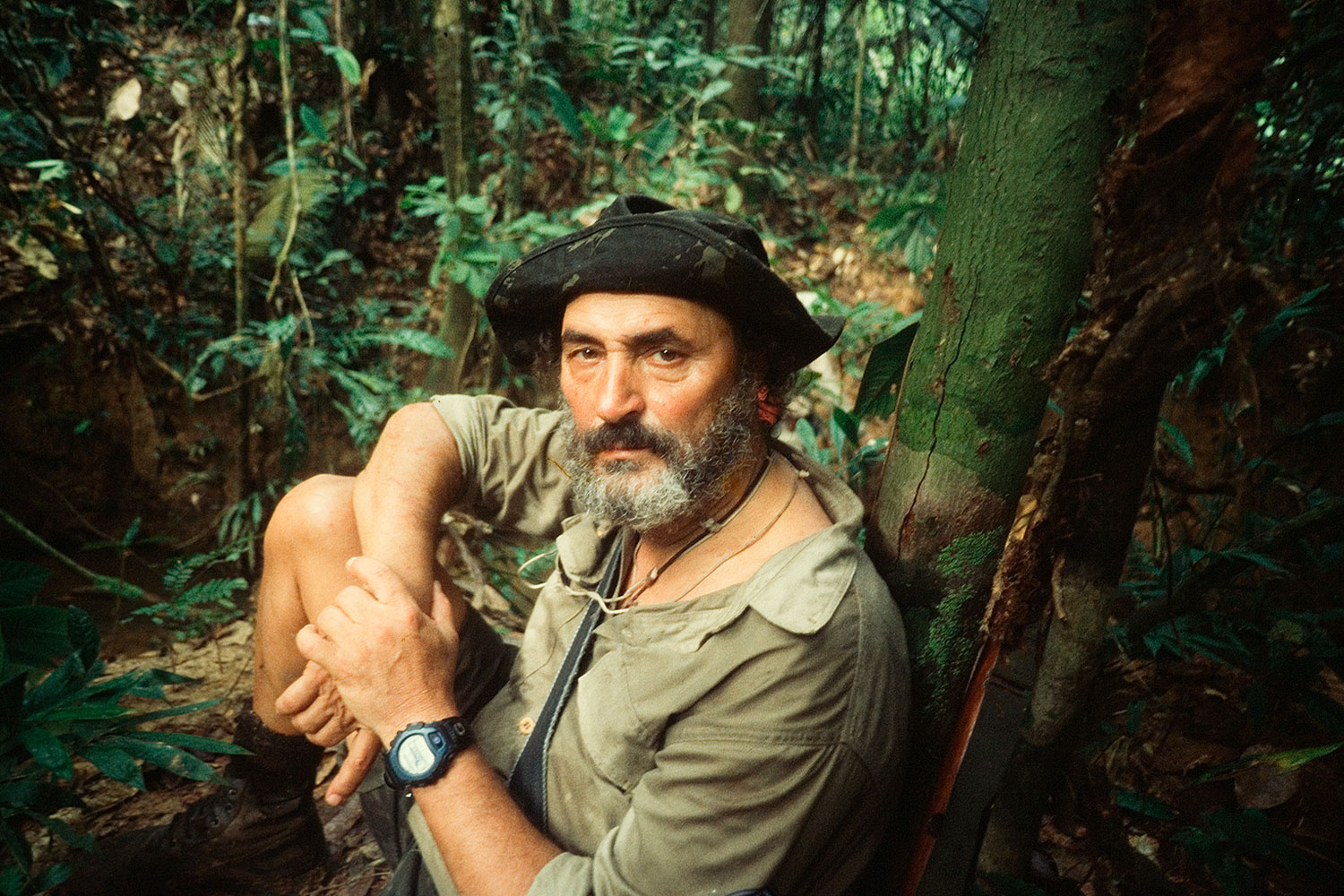

It was spring 2003; Wallace had just returned from a lengthy assignment in South America and was about to head off on a long-overdue family vacation when, he says, "National Geographic calls and asks if I can head back to Brazil by the weekend." The editor told him that Sydney Possuelo was leaving "any day now" on a trek into deep Amazonian wilderness. Also, "he has no idea when he'll be back."

Which is how Wallace came to be one of the few humans alive — or dead for that matter — to have come within spearing distance of the "Arrow People," one of the last uncontacted tribes living in the Amazon jungle.

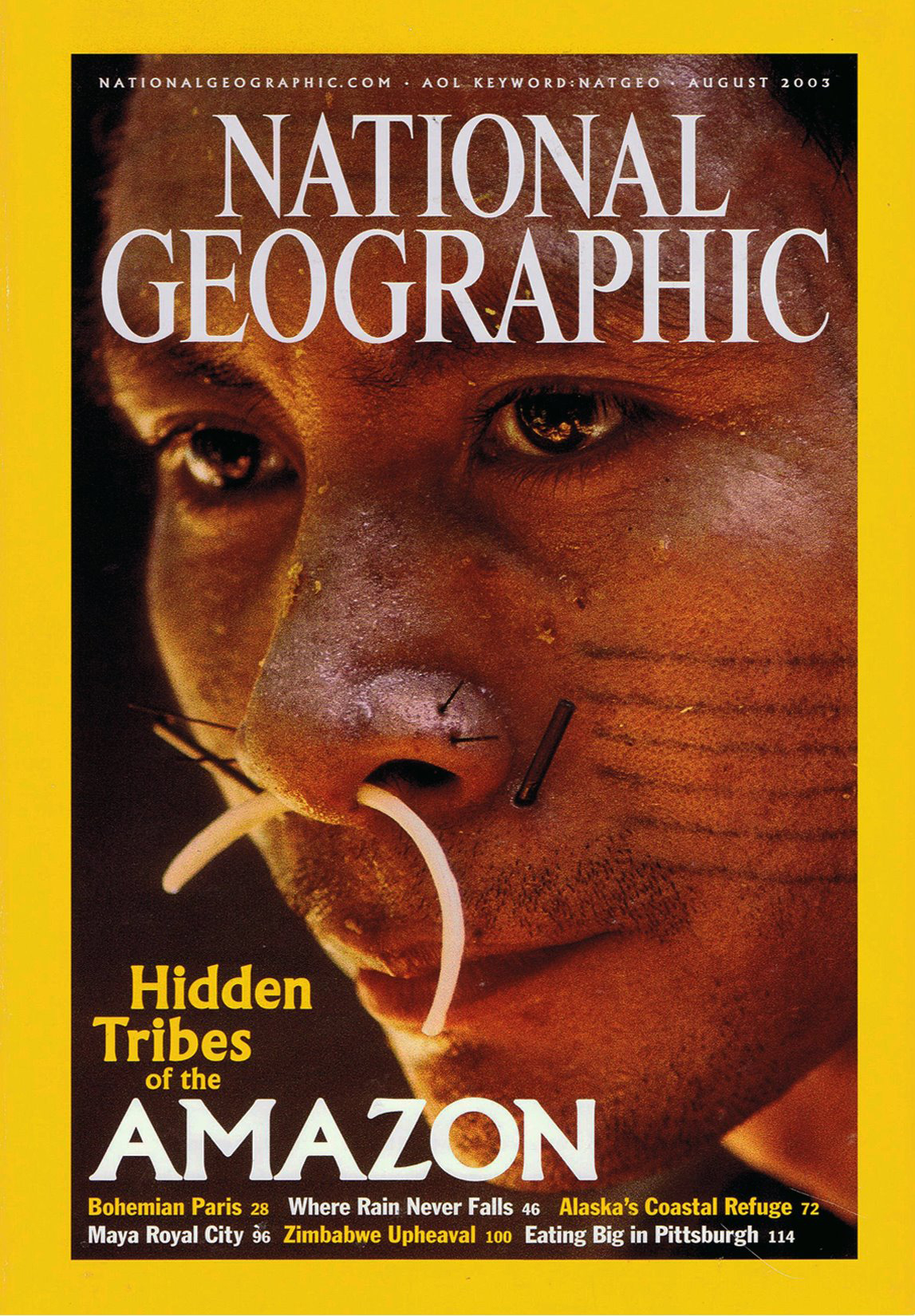

Wallace wrote his breakthrough 2003 National Geographic cover story about a three-month-long Amazonian trek with indigenous-rights advocate Sydney Possuelo.

Possuelo, explains Wallace, worked for Brazil's indigenous affairs agency, making peaceful contact with such tribes to protect them from the advance of "civilization" into their territories. But Possuelo came to understand the gravity of what he was doing. An entire tribe could be felled by the common cold. He had a change of heart. "Once you make contact," Possuelo told Wallace, "you begin the process of destroying their universe." He convinced the government instead to protect these tribes' territories. His current mission was to check on the wellness of the Arrow People without making contact with them.

Carve Out an Area of Expertise

Possuelo, Wallace, and their guides, members of three recently contacted Amazonian tribes, spent nearly three months all told in the depths of the Amazon. They traveled first by boat and skiff up Amazonian tributaries, then bushwhacked for 20 days through tortuous terrain searching for signs of the Arrow People. When they found such signs — fresh footprints, a piece of coiled vine, and a chunk of masticated sugarcane — it was cause for excitement . . . and alarm. "Possuelo has led us into one of the most remote and uncharted places left on the planet . . . this is the land of the mysterious Flecheiros, or Arrow People, a rarely glimpsed Indian tribe known principally as deft archers disposed to unleashing poison-tipped projectiles to defend their territory against all intruders, then melting away into the forest," wrote Wallace in the resulting August 2003 National Geographic cover story he calls "the turning point of my career." After that, Wallace became a go-to guy for stories on indigenous people, an expertise that would bring him back to the jungle many times, but also find him at an incongruous Mexican restaurant in one of the Earth's northernmost habitats, sharing chips and salsa with tribal leaders on the edge of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska. And, yes, those trips often meant disappointing family.

If Wallace has any regrets, that's the main one. "I am very sorry about that. I think my boys are proud of what I do despite the time together we lost out on; I'd like to think that they got more out of it. I don't know. What I do know is that my sons all are international travelers, all three are activists, all are devoted to learning languages and exposing themselves to other places, other people, and other points of view."

Explorer and indigenous-rights activist Sydney Possuelo on expedition, 2002.

Yanomami father and son in the Orinoco River Valley, Venezuela, 2001.

Get Off the Beaten Path, Way Off

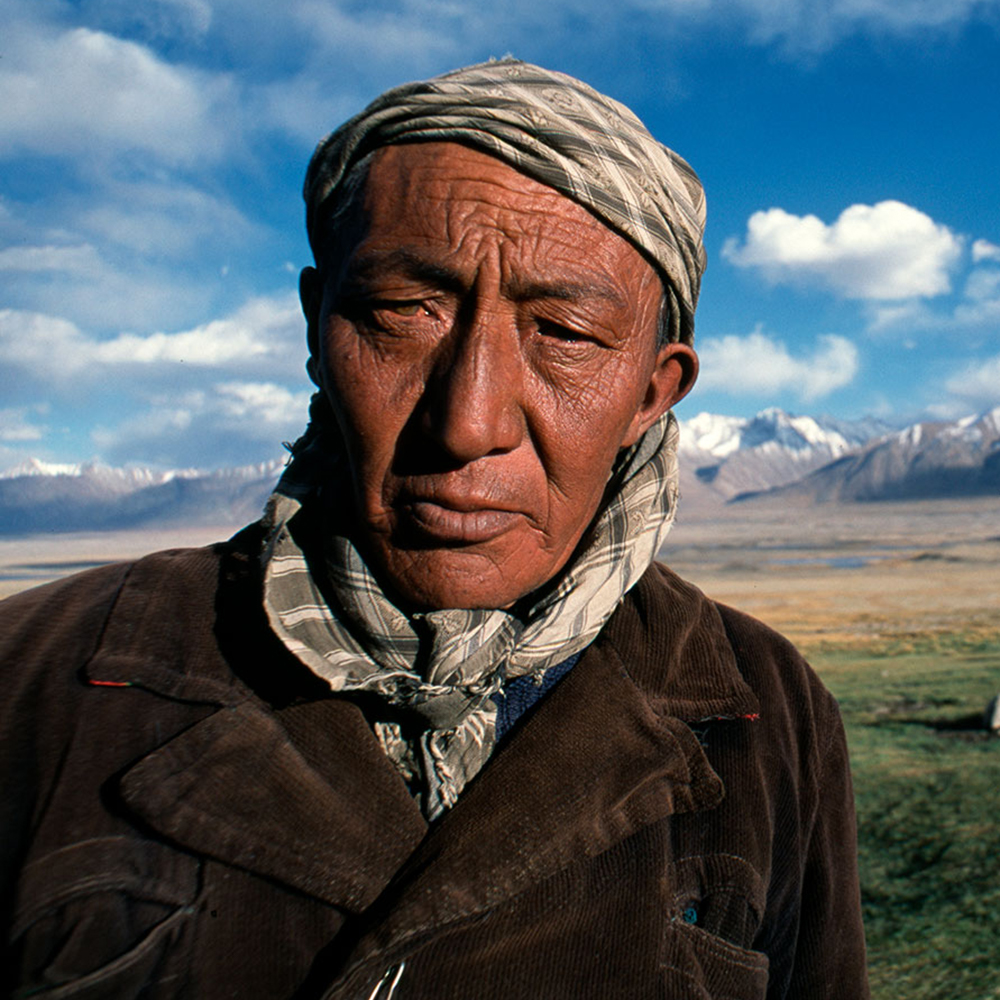

Two years later Wallace found himself in another remote corner of the world on another arduous trek, this time through the nearly-never-traveled Wakhan Corridor of Afghanistan, a mountainous region stretching between Tajikistan and Pakistan all the way to China, on a search for Marco Polo sheep with George Schaller, "the world's most influential naturalist." Wallace shakes his head in awe remembering how far beyond civilization they were. "It was so remote that in two months we never saw a single contrail from a plane. For two months we were never below 14,000 feet." They crossed hundreds of miles of valleys and mountain passes on foot.

"This was a spectacular, otherworldly experience to have a glimpse into centuries-ago travel with yaks and horses, what it was like for most of human history. We met nomads in encampments. It was an amazing adventure, like something you might read in 'The Hobbit.'

National Geographic Adventure asked Wallace to accompany naturalist George Schaller on a two-month journey through the remotest regions of Afghanistan.

Kirghiz shepherd in the Wakhan Corridor, Afghanistan, 2004.

Wallace with troops from the Army of Afghanistan in Tora Bora, Afghanistan, 2003. Photo by Peter Bergen

Master as Many Skills as Possible

Some of the most critical — and spectacular — assignments Wallace earned came his way in part because he is that rare journalist as skilled at photography as he is at wordsmithing. Wallace planned it that way, twisting his grad school schedules and syllabi to do all the possible sequences: radio, TV, newspaper writing, and photography. "I had already set my sights on going to Central America, and I knew that to be able to do that as a freelancer I was going to have to bring as wide a range of skills to bear as I could."

It paid off, and he's bullish now about getting his students to understand and master the basics of photojournalism. "Just because everyone has a phone — and camera — in their pocket doesn't mean everyone's a photographer. I think it's really important for students — no matter what they are planning to do — to be able to take a publishable photograph. So even in my writing classes, the assignments have a visual component."

Find Your Personal Shangri-La

Photos always mattered to Wallace. His parents gave him his first camera at age 8. And there was a photo on the wall in his parents' bedroom that held even more sway over him than anything he saw in National Geographic: An image of a man on a mountaintop, his Scottish grandfather whom he never met.

"I was spellbound by the riddles the portrait held. Where was it taken? Under what circumstances? Was my grandfather a hardbitten explorer or a charlatan? Was it my imagination, or did he look like a man so seized by wanderlust that he felt boxed in by conventional life?" Wallace's mother didn't have the answers. "My mother wasn't yet five when she waved goodbye to him on a Hudson River pier as he boarded an ocean liner bound for Asia in 1930. He promised to come back rich and famous. He did not return." She had a few clues, the photo, some published writings in which he claimed to have discovered an uncontacted tribe in Tibet. That's right, wanderlust and uncontacted indigenous tribes. It's not surprising Wallace was compelled to solve the mysteries surrounding this magnetic figure. By now he'd earned enough trust from editors that he was able to tailor two Himalayan assignments to this quest, from National Geographic Traveler in 2012 and a follow-up from Smithsonian Journeys Quarterly in 2015.

On the Traveler assignment, Wallace searched the wild landscapes of China's Yunnan province. In a village renamed Shangri-La to match the place in James Hilton's novel "Lost Horizon," Wallace's host tells him, "For Tibetans Shangri-La is not a real place but a feeling in our hearts. Everyone needs a personal Shangri-La." Three years later for Smithsonian, high in an outpost along India's border with Tibet, Wallace discovered the bungalow where his grandfather stayed during his quest. "It was the first time I ever walked into a room where I knew my grandfather had slept," says Wallace, something about the moment still resonating today, still playing yearning and satisfaction against each other.

Journalism Is a Job that Matters

Not every story requires a remote mountainous trek to uncover an original source. But the proliferation of media has muddied journalistic waters. In this age of alternative facts and unexamined social media posting, it's more difficult — and more crucial — to seek original sources and find firsthand experience, says Wallace. In his classes he addresses this issue by explaining, "This is a challenging profession, perhaps more challenging than ever in this environment, and it's more necessary than ever for people to have fact-based journalism so they can function in a democracy. This job is important. It can shine light on important things."

Tibetan Buddhist monks observe annual rites at Dongzhulin Monastery, Yunnan, China, 2012.

Dalit (Untouchable) girl with mother and infant sibling in Haryana State, India, 2004.

Kindergarten children in Boyacá, Colombia, 2004.

Schoolgirl teased by classmates in Gazipur, Bangladesh, 2004.

Kurdish woman tending her flock in Hasankeyf, Turkey, 2004.

Boatman brings wedding party to riverbank in Narayanganj, Bangladesh, 2004.

Brick kiln workers in Dhaka, Bangladesh, 2004.

Kurdish children at play in Mardin, eastern Turkey, 2004.

Young businesswomen in Aden, Yemen, 2004.

QUEST: A search for his grandfather brought Wallace to Himalayan monasteries (first). The World Bank sent him around the world in 56 days to photograph beneficiaries of development projects (the rest).

You don't have to go to the ends of the earth to find those things. Last semester Wallace co-taught a publication practicum with his colleague Steve Smith, in which the class produced a documentary about the local undocumented immigrant community. "It's an important story happening in our backyard. UConn students could go through four years and not know that in their midst are students who are undocumented, afraid that they and/or their parents will be deported," says Wallace.

Many of his students say they are in journalism to make a difference, and his classes make them believe they can. Camila Vallejo '19 (CLAS) was just hired at NPR and feels prepared for her new challenge thanks in large part to Wallace. "As a seasoned features writer and war correspondent, he highlighted the good as well as the raw truth behind being a reporter. He taught me how to choose my words wisely, the importance of setting the scene in any piece, and never to rely on technology because a reporter's notebook really is your best friend."

For his part, Wallace says he tries to stress both the honor and responsibility a journalist has in telling other people's stories. "It's a challenging time to be a journalist, so these students deserve the best. I try to mentor them as best I can."

Don't Listen to Everything Your Teachers Tell You

And finally, in pursuit of that personal Shangri-La, don't listen to everything your teachers tell you. In those final weeks of journalism graduate school Wallace's professors at the University of Missouri told him not to bother trying to get work in Central America, that there were "hundreds of reporters trying for those spots overseas."

Instead of listening to them and applying for stateside jobs, he found his way into CBS News headquarters in New York and asked not for a paid job but for the "stringer" position that would pay by the story and get him the important press credential to tuck into his pocket with that $50 in cash. And he headed for El Salvador to "dodge bullets for chicken feed." It was worth it, he says.

After all, it opened up the world and gave him a ringside seat to witness stories that may have otherwise gone unknown to the rest of us.

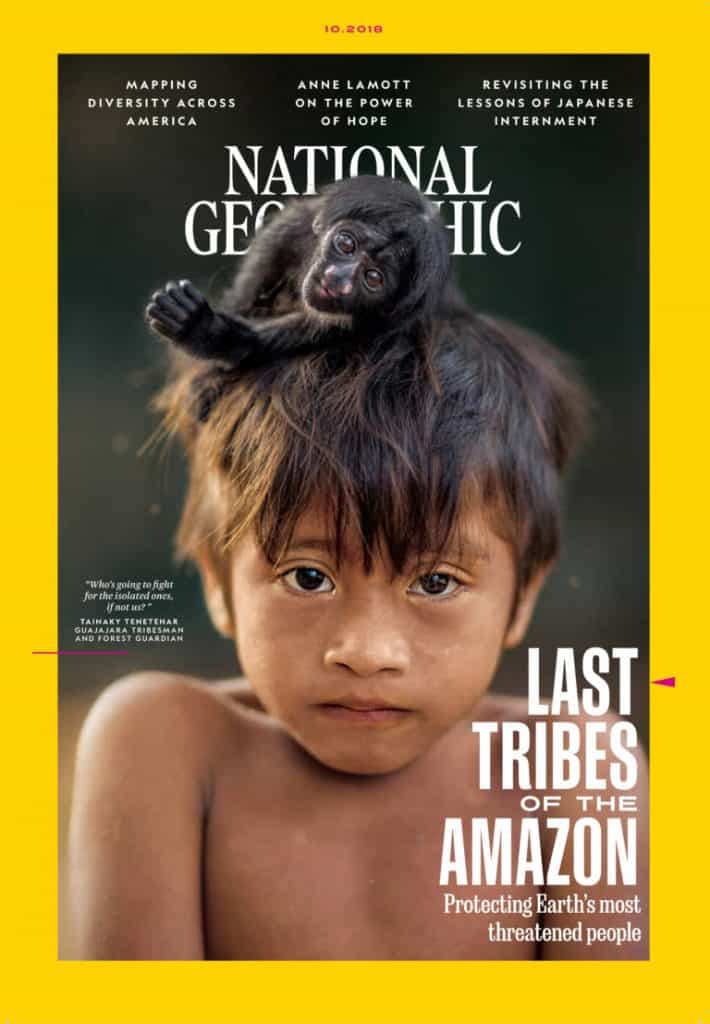

In Wallace's most recent National Geographic cover story of October 2018, he writes about the plight of the endangered Awá tribe

Group of young Awa men with their hunting bows and arrows in Juriti, Awá Indigenous Territory, Brazil, 2017.

Awá woman, in a toucan feather headdress, holds a hunting bow and arrows while a pet monkey sits on her opposite shoulder in Carú Indigenous Territory, Brazil, 2017.

Leave a Reply