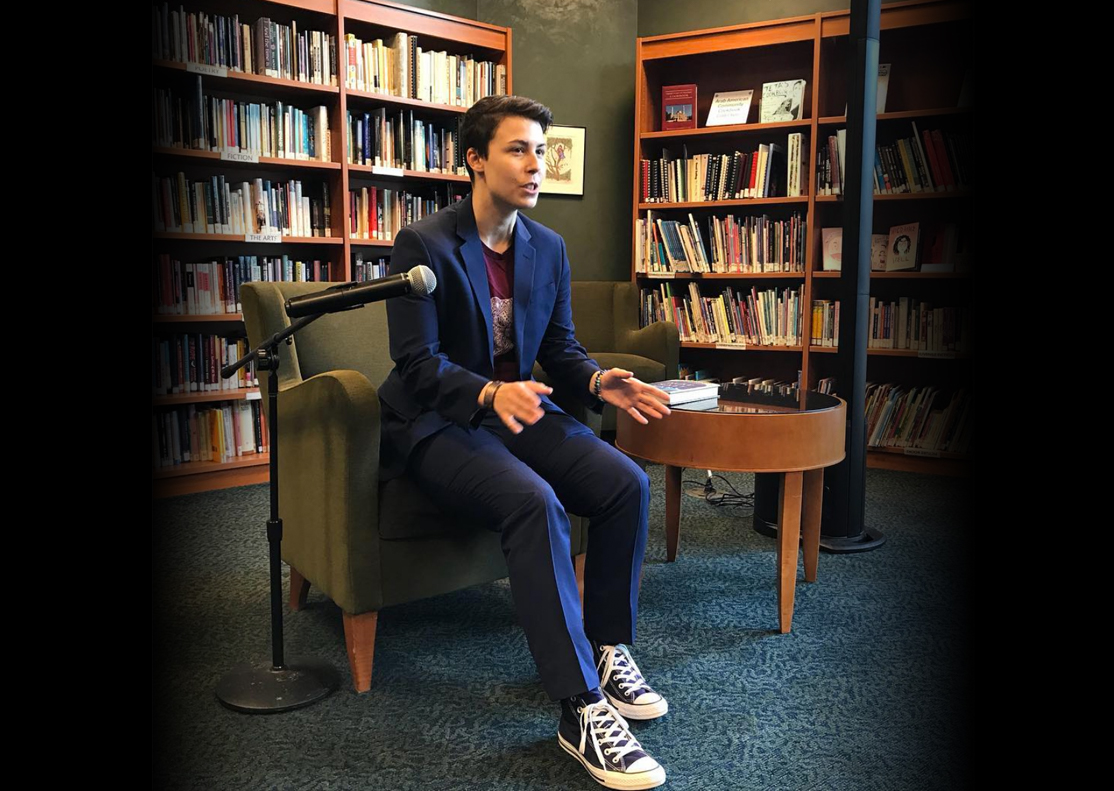

Jennifer Zeynab Joukhadar '08 (CLAS)

In 2015, after years of intense study, a bachelor's in molecular and cell biology followed by a Ph.D. in pathobiology as well as two postdoctoral fellowships, Jennifer Zeynab Joukhadar '08 (CLAS) walked away from science to pursue her childhood dream — to be a novelist.

Jennifer Zeynab Joukhadar '08 (CLAS)

In 2015, after years of intense study, a bachelor's in molecular and cell biology followed by a Ph.D. in pathobiology as well as two postdoctoral fellowships, Jennifer Zeynab Joukhadar '08 (CLAS) walked away from science to pursue her childhood dream — to be a novelist.

"I wanted to give myself a chance to write full-time for six months to a year and see where it led," she says.

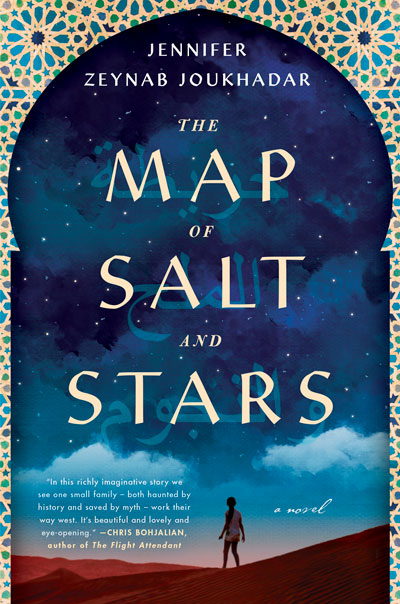

Where it led is to Joukhadar's first Ânovel, The Map of Salt and Stars, which was recently published by Simon & Schuster. The book's dual narrative follows two fatherless girls as they each embark on long and dangerous journeys across the Middle East and North Africa.

As 12-year-old Nour flees the Syrian civil war with her family, she comforts herself by recounting a story her father used to tell her about Rawiya, a teenage girl who apprentices herself to a medieval mapmaker charting trade routes. Joukhadar switches back and forth between the two tales that are as similar as they are different. Rawiya's story is a fairy tale; Nour's is a nightmare.

Says Kirkus Review, "Joukhadar plunges the Western reader full force into the refugee world with sensual imagery that is immediate, intense, and at times overwhelming."

When Joukhadar began work on her novel, the Syrian civil war had raged for four years. As a Syrian American (her father emigrated from Syria to Manhattan), Joukhadar could not tune out the news of the fighting and the refugees. "I was thinking of the ways my community was grieving for people that were lost, places that were lost. I wondered if could we redefine home as something other than a place, so we can't lose it. I started to think of the power of stories, not to just heal but to be vehicles of what we can take with us."

Though the war felt personal for her, what the author knew of it was mostly from news accounts. Joukhadar grew up in Manhattan and in Fairfield, Connecticut. Her mother is American.

To tell Nour's story Joukhadar turned to first-hand accounts of refugees, reading as many as she could. She also researched her own passions, geology and mapmaking, which she weaves into the book as symbols and plot devices. Nour, for example, carries a piece of lapis lazuli riven by bands of salt, a metaphor for the unavoidable trauma in life. Though Rawiya's story is fantastical, complete with a kind of monstrous bird, she apprentices to al-Idrisi, a real-life Arab medieval geographer who was one of the most advanced mapmakers of his time.

Joukhadar also drew on her experience with synesthesia, a neurological condition that causes people to see shapes and colors in their mind's eye in relationship to music, numbers, or other stimuli. In the book, Nour describes the pink of her sister's laugh and the red of a kitchen timer's chime. "It brings a little bit of color into her world even when she goes through difficult times."

Though Joukhadar began writing stories in third grade, she set her sights on science in college. Her family encouraged her to have a backup plan to writing, and a career as a research scientist became that. She went to Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, but was drawn to UConn's science program and so switched in 2007. Here, she took a heavy course load and worked in Professor Michael Lynes' immunology lab. That didn't leave her much free time, but she kept writing, finishing short stories and a novella.

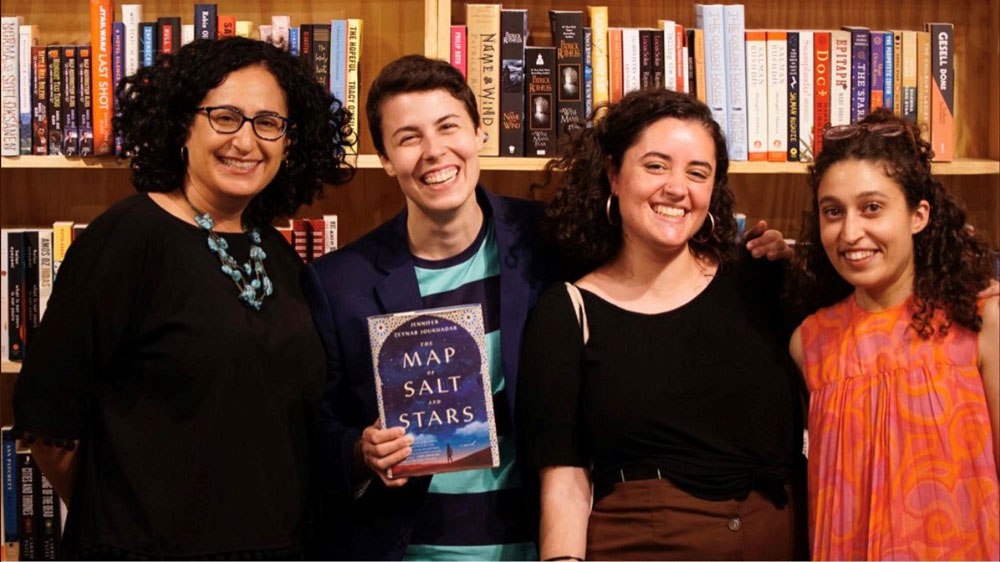

For the past year Joukhadar has called nowhere home as she went from writer's residency to writer's residency, including a two-month stint in Morocco, her first visit to Northern Africa and a chance to hone her Arabic. She's been working on her second novel, which has to do with Syrian immigration to the U.S. historically. "People don't know they have been immigrating [to the U.S.] since 1860."

Ironically, as she has worked on that book, the Trump administration essentially banned Syrians from even visiting the U.S. While she's been on the road to promote her debut novel, Joukhadar says people at her readings often ask her what they can do to help Syrians. If nothing else, she urges them to read what Syrians themselves have to say about the war.

She hopes her novel is "a gateway for people to seek out the voices of people raised in Syria, to hear them in their own words."

—Amy Sutherland

Leave a Reply