"It's time to write,

to read, and to

drive with the top down."

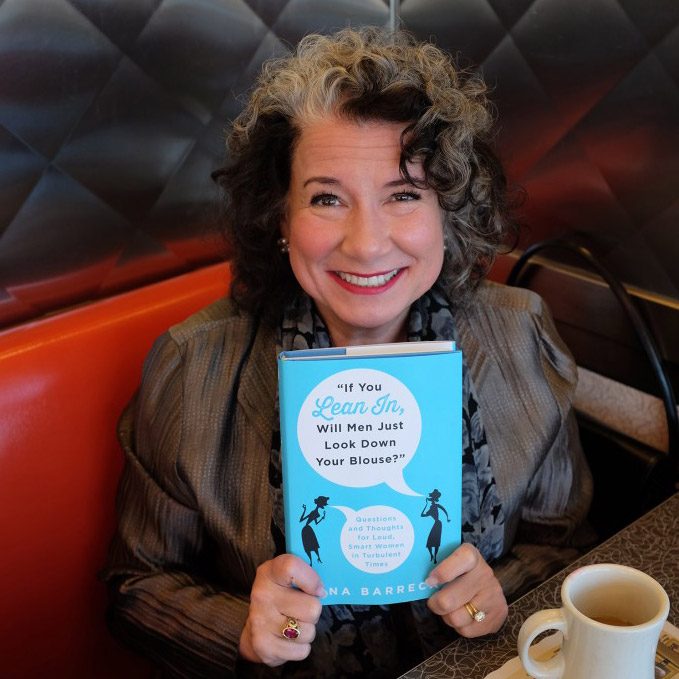

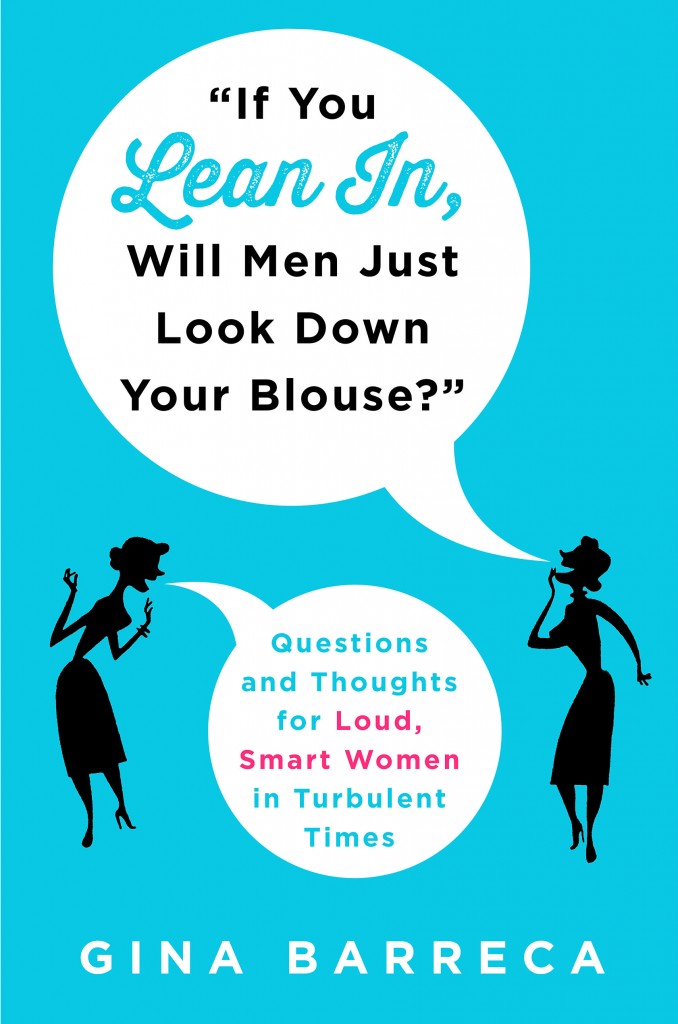

Gina Barreca's latest book is as funny and forthright as her previous memoirs. But this one, she says, is even more personal and more revealing — examining relationships she holds most dear, including that with husband Michael Meyer, who also taught English at UConn.

I had enormous fun writing If You Lean In, Will Men Just Look Down Your Blouse? And I learned a lot. Yes, this book takes on a number of social and cultural issues — everything from the "Twilight" and "Fifty Shades" phenomena to the powers of Spanx and Goji berries. But it's different from most of my earlier work, because it's more personal and unguarded.

We get braver and more honest as we get older. I don't know if it's true that we women become invisible as we age, but we certainly become more audible. We become more politicized, less willing to simply nod and smile if we disagree, and more willing to stand up for ourselves and others (instead of leaning in — I'm not a Sheryl Sandberg fan, and that's where the title comes from; there's a chapter about my issues with her work). And both women and men, somewhere between 40 and 50, begin to distinguish what actually makes them happy from what they've always done to please others. Being able to define that difference is an accomplishment. It's one of those areas of expertise that takes at least 10,000 hours to learn. At a certain age, you finally become the indisputable authority on the subject of yourself.

I know I'm getting braver as I get older — and that won't come as a big surprise to anybody. Having taught creative writing classes at both the undergraduate and graduate level, I've always emphasized the need for writers at every level to figure out what story they're really trying to tell. It's usually buried four or five paragraphs deep and embedded in a particularly sharp, fierce, sometimes off-the-cuff line the writer might have been surprised to hear herself or himself say. It's rarely the well-groomed, much-rehearsed, and overwritten sentence that grabs a reader by the throat.

I tried to respect that in my own writing while completing this manuscript. While nobody could accuse me of keeping my personal life out of my earlier books (after all, I wrote a memoir about my time as one of the first women at Dartmouth College titled Babes in Boyland, and my first book, They Used to Call Me Snow White but I Drifted, draws deeply on my Italian upbringing), this latest collection takes more risks.

For example, in a section titled "If You Met My Family, You'd Understand," there's a chapter about questions I wished I'd asked my mother before she died (she was 47 and I was 16). There are essays about how my parents' troubled marriage helped clarify what I wanted from my own. And while deep fears aren't necessarily funny, there's an essay about my own panic attacks that includes an incident with a butterfly net. There's also a section titled "If You Run With a Bad Crowd, Can You Call It Exercise?" "Real" humor is real.

I try to write about teaching, writing, my professional life, and my own relationships with honesty as well as humor. When I write about my friends and family, I ask their permission to tell their stories as well as my own. Most of the time they're generous enough to grant it.

The excerpt below is from an essay about my husband, Michael Meyer, on the day he retired from the English Department at UConn. I first published it with The Chronicle of Higher Education, but even though he's the focus of the essay, I did not, in this case, show it to him first. I wanted it to be a surprise. It was a delight to adapt it for If You Lean In and to have it here in UConn Magazine, since Michael was everybody's favorite professor of American Literature.

"Save the Last Class for Me," an excerpt from If You Lean In, Will Men Just Look Down Your Blouse?

My husband is teaching a class on the poetry of Emily Dickinson this morning.

He's been teaching Dickinson for 40 years; it's not like there was a lot of prep involved.But today is different for two reasons: Not only is it the last class of the semester; it's also the last class my husband, Michael Meyer, is going to teach. After today — or, to be more precise, after next week's exams — he will have retired from his work as a university professor.

It's not like Michael's going out of business entirely, since he edits all those versions of The Bedford Introduction to Literature that you see everywhere, but he's done with the classroom part of it.

Maybe I should say he's done with the "office" part of it.

Michael has always been one of those teachers admired and respected by those he's taught; the Meyer Diaspora of successful former UConn students offers testimony to that.

His current students can't believe he's been doing this since before their parents were born.

What they also can't believe is that the two of us are married to each other.

Michael looks and often sounds like an English professor out of central casting. This morning, for example, he left for work wearing a tweed jacket, blue shirt, and striped tie, with his briefcase firmly in hand. His salt-and-pepper beard was neatly combed, his dark eyebrows lifted in his usual expression of amusement, and his glasses were — as they always are — spotless. This is no rumpled academic. This is the Man. He's distinguished, handsome, and authoritative.

Me, I go to school looking like either Anna Magnani or Ethel Merman. After 23 years of teaching in Connecticut, I still look like I'm there to deliver a pizza rather than teach a class. I still sound like I'm from New York and I wear heels so that my students hear me clicking down the hall as I approach.

Michael and I are almost as different as it's possible to be and still be part of the same department — let alone part of the same marriage — so it's no wonder our students are shocked to discover we're together.

They'll miss him, as will our colleagues. But, as Michael says, "It's time." The son of a longshoreman and a factory worker, Michael's held a job since he was 15. He's now 65. It's time to write, to read, and to drive with the top down.

After all, as a friend of ours said, "After you turn fifty, you're cramming for finals."

Dickinson suggests as much in "Apparently with no surprise" when she writes about the inexorable and indifferent passage of time, as "The Sun proceeds unmoved/to measure off another Day." Of course I'm looking forward to the next several years being as best described by the title of another Dickinson poem, "Wild Nights — Wild Nights!"

To my distinguished colleague: Congratulations on years well spent and classes well taught.

Well done.

My husband is teaching a class on the poetry of Emily Dickinson this morning.

He's been teaching Dickinson for 40 years; it's not like there was a lot of prep involved.But today is different for two reasons: Not only is it the last class of the semester; it's also the last class my husband, Michael Meyer, is going to teach. After today — or, to be more precise, after next week's exams — he will have retired from his work as a university professor.

It's not like Michael's going out of business entirely, since he edits all those versions of The Bedford Introduction to Literature that you see everywhere, but he's done with the classroom part of it.

Maybe I should say he's done with the "office" part of it.

Michael has always been one of those teachers admired and respected by those he's taught; the Meyer Diaspora of successful former UConn students offers testimony to that.

His current students can't believe he's been doing this since before their parents were born.

What they also can't believe is that the two of us are married to each other.

Michael looks and often sounds like an English professor out of central casting. This morning, for example, he left for work wearing a tweed jacket, blue shirt, and striped tie, with his briefcase firmly in hand. His salt-and-pepper beard was neatly combed, his dark eyebrows lifted in his usual expression of amusement, and his glasses were — as they always are — spotless. This is no rumpled academic. This is the Man. He's distinguished, handsome, and authoritative.

Me, I go to school looking like either Anna Magnani or Ethel Merman. After 23 years of teaching in Connecticut, I still look like I'm there to deliver a pizza rather than teach a class. I still sound like I'm from New York and I wear heels so that my students hear me clicking down the hall as I approach.

Michael and I are almost as different as it's possible to be and still be part of the same department — let alone part of the same marriage — so it's no wonder our students are shocked to discover we're together.

They'll miss him, as will our colleagues. But, as Michael says, "It's time." The son of a longshoreman and a factory worker, Michael's held a job since he was 15. He's now 65. It's time to write, to read, and to drive with the top down.

After all, as a friend of ours said, "After you turn fifty, you're cramming for finals."

Dickinson suggests as much in "Apparently with no surprise" when she writes about the inexorable and indifferent passage of time, as "The Sun proceeds unmoved/to measure off another Day." Of course I'm looking forward to the next several years being as best described by the title of another Dickinson poem, "Wild Nights — Wild Nights!"

To my distinguished colleague: Congratulations on years well spent and classes well taught.

Well done.

From ginabarreca.com

Gina Barreca is fed up with women who lean in, but don't open their mouths. In her latest collection of essays, she turns her attention to subjects like bondage which she notes now seems to come in fifty shades of grey and has been renamed Spanx. She muses on those lessons learned in Kindergarten that every woman must unlearn like not having to hold the hand of the person you're walking next to (especially if he's a bad boyfriend) or needing to have milk, cookies and a nap every day at 3:00 PM (which tends to sap one's energy not to mention what it does to one's waistline). She sounds off about all those things a woman hates to hear from a man like "Calm down" or "Next time, try buying shoes that fit". "'If You Lean In, Will Men Just Look Down Your Blouse?'" is about getting loud, getting love, getting ahead and getting the first draw (or the last shot). Here are tips, lessons and bold confessions about bad boyfriends at any age, about friends we love and ones we can't stand anymore, about waist size and wasted time, about panic, placebos, placentas and certain kinds of not-so adorable paternalism attached to certain kinds of politicians. The world is kept lively by loud women talking and "'If You Lean In, Will Men Just Look Down Your Blouse?'" cheers and challenges those voices to come together and speak up.

In fall 1978, while a student at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, I had the pleasure of having a graduate-level class in Dr. Meyer’s American Romanticism, a survey of the major writers of the mid-nineteenth century, including Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman, and Melville. At the time, he was involved in co-authoring “A New Thoreau Handbook,” with Walter Harding, which was published in 1980. I purchased and kept a copy of the book for a number of years, that is, until it was lost during a move from North Carolina to Pennsylvania, or, at least, that was the most likely scenario. It was only recently when I was re-reading Thoreau, that Dr. Meyer’s class came to mind, especially his brilliant insights into Emerson’s and Thoreau’s lives and teachings, because it was those two elements that defined both men. After receiving my degree in 1980, and subsequent years teaching English on the secondary level, among other vocations, the next several years, I learned that Dr. Meyer had returned to his roots in Connecticut to resume teaching in his specialty subjects but mostly Thoreau. I only recently unearthed a used copy of his and Walter Harding’s Thoreau handbook. However, this copy was special because Dr. Meyer had signed it, providing a long-lost link to a teacher who was a significant influence in my life. I happened to find this article about him and his wife regarding their retirement and sharing the many things that brought them together in the first place. I don’t know if he will see this because of the number of years that has passed between us but if he does, he is not forgotten, and maybe like his book, only misplaced to be re-discovered.