ROCK ON

Geology professor Robert M. Thorson is crazy about stone walls. He spent years trying to dig up proof that former University president Homer Babbidge shared that love — and along the way found evidence of UConn's first recorded student protests.

By Robert M. Thorson

ROCK ON

Geology professor Robert M. Thorson is crazy about stone walls. He spent years trying to dig up proof that former University president Homer Babbidge shared that love — and along the way found evidence of UConn's first recorded student protests.

By Robert M. Thorson

Homer Babbidge Jr., a beloved former president of the University of Connecticut, was head-over-heels in love with New England's historic stone walls.

Or so I heard when I arrived on campus to teach geology in 1984. I heard through the grapevine that during the '60s, Babbidge required students to build walls in order to graduate"¦that he taught credit courses on their construction"¦that this or that was a Babbidge-built wall"¦and that he left a legacy of materials documenting his efforts in the University archives.

Being curious, I started trying to substantiate these rumors, asking around the Storrs campus during the late 1980s. I remember asking the reference staff of the Babbidge Library to investigate on my behalf. They found nothing. In the mid-1990s, shortly after the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center was up and running, I asked its archivists the same thing. Nothing. When the University's official history was published in 2006 as Red Brick in the Land of Steady Habits, I searched every page. Nothing. I even asked its lead author, Bruce Stave, if he had run across anything connecting Babbidge and stone walls during his research. Again, nothing.

Gradually and grudgingly, I concluded that the link between Homer Babbidge and New England's famous stone walls consisted of nothing more than a few just-so stories bundled into oral tradition and crystallized into institutional mythology.

Then, totally out of the blue, I learned that the rumors were true.

"The land of steady habits"

In 2003, I traveled to Islesboro, Maine, to give a speech on historic stone walls for Jack McConnell. He's a professional photographer extraordinaire who, while recovering in the hospital from a heart operation, read one of my books and became infected with the stone wall virus. Jack's reaction was to change his trade name to "Stonewall Jack," hit the back roads with his camera, print and frame dozens of enlargements, open a gallery for Islesboro's summer people, and invite me to speak at its grand opening reception. What a wonderful night it was.

One of those summer people in the audience was Alex Babbidge, Homer's son. The Babbidge family has lived and summered on this beautiful island on the west side of Penobscot Bay since the age of sail, when their family business used clipper ships for the Atlantic trade. For reasons I can't remember, Alex, Jack, and I ended up on the front porch of the traditional Babbidge family place, eating snacks, drinking cold beer and lemonade, smelling the salt air, and discussing island geology. Waiting for the right moment, I finally asked Alex if the stories about his father's interest in stone walls were in fact true.

"Yes," he replied unequivocally, saying he had run across something in the family papers a few years earlier. Before we got down to details, however, we were interrupted by a child needing to be put to bed. As we bid each other a hasty good night, I wondered if I'd ever hear anything more.

Two years whizzed by. Then, in December 2005, I received an unexpected email from long-lost Alex. He had rediscovered the manuscript he had alluded to in Islesboro, and had already popped it in the mail. Within a few days, I was reading the unpublished text of a speech Homer had given to the Monday Evening Club in Hartford on Dec. 3, 1971, during the final phase of his presidency. This civic organization had been operating continuously in Hartford since the first decade of the 19th century, when fieldstone walls were rapidly criss-crossing the agricultural landscape of the new republic.

"How to Build a Stone Wall," the title of Homer's speech, was clearly a ruse. His main purpose was to confess — unabashedly — his "love affair with the New England stone wall." His strong feelings on this subject had been ignited when he was a high school student living in a far-off land devoid of stone walls: Amherst, New York. There, he realized how much he missed historic stone walls as an evocation of his New England boyhood and a memorial to the hard work of previous centuries.

During his exile, Homer read and reread a favorite poem, "Mending Wall" by Robert Frost, as a "source of comfort and reassurance." Homer also recalls a poignant moment during a return to New England after some time away: "Having left the Grand Central Station at dawn, I caught sight of the first stone wall I'd seen in years. I felt I was home again; home in the land of steady habits, a land of ordered, mutually respectful relationships symbolized by those walls."

A decade later, Homer's romantic attachment to stone walls was ruptured by none other than Robert Frost himself. As a Yale graduate student, and the youngest fellow of its Pierson College, Homer attended a reading of "Mending Wall" by the elderly poet, then the most senior fellow of the college. Homer listened in "shocked disbelief" while the poet "ridiculed his farm neighbor, as he recited with nothing less than contempt, the line I most revered, 'good fences make good neighbors.'" Frost, he concluded, wrote the poem as a "trite hand-me-down" to his thoughtless and ignorant neighbor, who epitomized the old Yankee ways in southern New Hampshire.

Homer's memory of that night lay buried during the transition from University student to University president. "Now another twenty years have passed," he writes in his speech, "and I still haven't shaken the effects of that evening. I still grapple, in odd moments, with the elusive 'elves' of Mr. Frost's skepticism, and try to reconcile them with my continuing affection for the stone wall."

"I still believe in the stone wall"

By the time he had finished typing his speech, Homer had ironed out the wrinkles of his feelings about stone walls in general and the line "good fences make good neighbors" in particular. After ruminating for a few paragraphs, he concludes: "It seems important, if I am to have my hobby [of building walls] and my conscience, too, that the point be made — at least among friends — that stone walls are not simply or even necessarily, devices for fencing in or fencing out"¦. The New England stone wall is as nothing more or less than a tidy waste-disposal system." No longer need they symbolize the "dark and hidden motivation" of excluding neighbors or, worse, of confining one's self away from significant others. Having found this personal middle ground, he concludes: "At any rate, I think I am now at peace with myself on the subject of stone walls."

Near the end of his speech, Homer recapitulates by asking: "Is building or mending walls a form of anti-social behavior?" He answers no. Resoundingly so. "I still believe in the stone wall," he continues, "not to exclude others, but to describe my land, and in doing so, help to define myself."

Given the speech's historic context, I strongly suspect that "my land" in the sentence above refers to the campus he presided over. And that the phrase "to define myself" refers in part to the Babbidge presidency. Indeed, with his own hands Homer helped build the University of Connecticut into a modern university by gracing its grounds with walls built from the residue of an earlier era, when Charles and Augustus Storrs were thinking of donating their fields and pastures to the state for use as an agricultural school.

Homer guided the University from 1962 to 1972, a decade of turbulent unrest associated with civil rights, political assassinations, environmental politics, the women's movement, and the Vietnam War. During this time of profound societal disorder, Homer worked hard to impose architectural order on stone, to transform random fragments of rock into stable and beautiful dry-stone walls. Stonework became a hobby that defined who he was.

His stonework also can be seen as a physical metaphor for the use of his presidential authority to help prevent campus from being heaved apart"¦whether by frost in the ground or foment in the air. Indeed, the chaos of continuous culture change and of natural soil processes is tireless. For Homer, dry-stone masonry was also a meditation in which muscle, intellect, and soul came together in an outdoor setting.

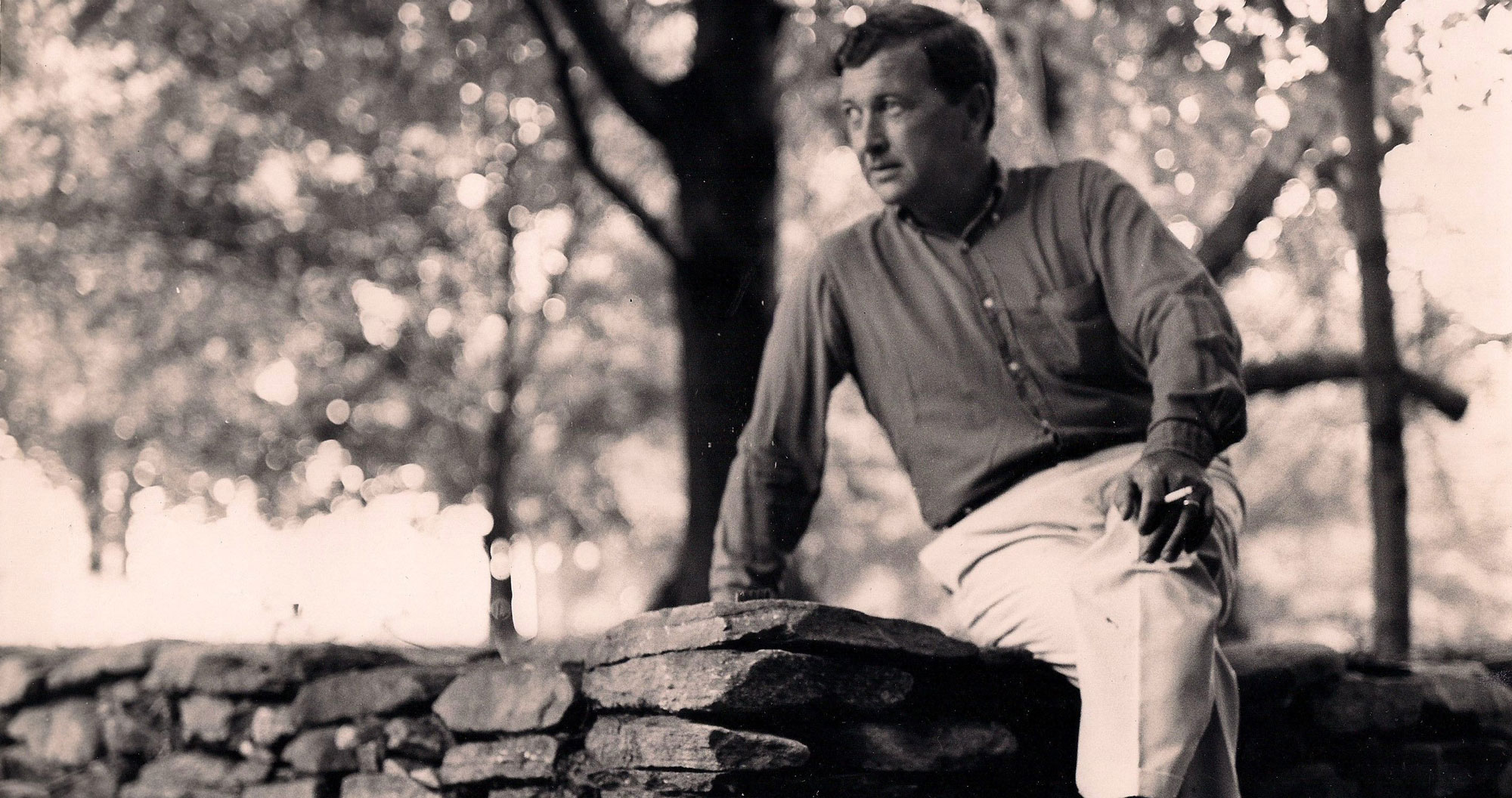

Homer Daniels Babbidge, Jr. (1925-1984) was president of the University of Connecticut from 1962 to 1972. It was a time of great growth in graduate education, library holdings, budget, staff, and programs. It was also a time of great turbulence and student protests. When Babbidge resigned in 1972, more than 7000 members of the campus community signed a petition asking him to stay.

"I won't pick rocks anymore"

To help assuage the unrest of the late '60s and early '70s, Homer pulled another trick from his bag. He reached deep into campus history to the year 1899, to a "Victorian version of the student uprising." This event was a mass campus protest against the requirement that students pick and haul stones and convert them into walls under the pretense of "instructive labor." This quote — from the desk of the president himself — confirms that wall-building by students was indeed mandatory and therefore required of graduates, whether explicitly or implicitly.

With the New England farm culture in decline, with industrialization accelerating, and with an agricultural school being transformed into an academic college, UConn students simply refused to continue the Neolithic practice of picking stones from farm fields. To rouse the crowd during their protests, they wrote what the campus newspaper called "the most popular song of the day."

Here are the lyrics from the 1890s, as quoted by Homer in his speech:

A freshman once did come to Storrs

To see what he could see.

But when he saw the rocks that lay

Scattered all over, he swore

As a freshman sometimes will and said

I won't pick rocks anymore.

And here is the chorus, as published in UConn's official history:

I won't pick rocks anymore

I have picked for years

On my father's farm and

I won't pick rocks anymore.

The students won their 1899 protest against forced field labor. But physical exercise remained crucial in the minds of educational reformers. UConn athletics — if not born in that moment — surged in importance as a part of campus life. Stretching the truth just a bit, I assert that the conversion of field-picked stone into walls was UConn's original sport, the foundation of its athletic dynasty.

Homer Daniels Babbidge Jr. established the University of Connecticut Foundation in 1964 to enhance the University's growth and prestige. He established something else that year as well. Fronting Gulley Hall is the President's Garden, the aesthetic epicenter of campus (and stop number five on the geologist's tour of Storrs campus at right). Enclosing that garden is a dappled-gray, lichen-crusted fieldstone wall built in the style of old New England.

So here's what I'm thinking. During breaks between the slow meetings needed to build the UConn Foundation on paper, Homer went outside to heft stones to help the Horticulture Club build those garden walls. He would have understood that the outward growth and expansion of a modern institution requires a solid inner core tied to the past, especially in a state known as the "Land of Steady Habits." Perhaps each succeeding UConn president should heft a stone or two, if only to honor this great man's insight and the plain fact that this great University began as a 19th-century agricultural school.

Find the long-lost original transcript of Babbidge's 1971 "How to Build a Stone Wall" speech to The Monday Evening Club here. While you will not learn how to build a stone wall, you will find Babbidge's comparison of the New England stone wall to the Great Wall of China and the Berlin Wall as well as more about UConn's Victorian practice of having students "pick stones."

Robert M. Thorson's Walking Tour of Storrs Campus

Illustrations by Virge Kask '79 (CLAS), '84 MA

Painted Rock

A geologist can see through the layers of paint (students paint this rock at least once a day in peak season) to focus on the shape, in this case a triangular slab with foliation and fractures. This strongly suggests the rock is local high-grade metamorphic rock and was therefore encountered somewhere nearby during a construction phase. It was likely dropped by the ice sheet that left here about 17,000 years ago.

Sundial

The shadow the dial casts proves that the Earth is a planet that spins on its axis and revolves around the Sun. The base is made of a dense igneous rock known as gabbro. This specimen, called Prairie Green, is from Quebec City.

Harvest Joy

The estate of Italian-American sculptor Paolo Abbate (1884Â"“1973) gifted this bust, titled "Harvest Joy," to the The William Benton Museum of Art. It's made of a massive, coarse-grained, bedded limestone, probably Indiana Limestone, also called the nation's building stone, used in the Empire State Building, the White House, and other icons.

President's Garden

This dappled-gray, lichen-crusted fieldstone wall frames the President's Garden, which fronts Gulley Hall and is at the epicenter of campus. Most of the rock is locally quarried "gneiss."

Dinosaur "Footprint"

Eubrontes, Connecticut's state fossil, is not a bone but the cast of a footprint (the slab is upside down to the viewer). The rock is from the East Berlin Formation, a mica-rich sandstone from Rocky Hill, Conn.

House of Many Stones

The stone house was built mainly of hand-selected local stone and mortar by a former faculty member. Inside is a collection of the official stone from each state. Connecticut's state rock is brownstone, an iron-stained sandstone. The one on display here is a breccia, formed in a fault zone, in which fragments of brownstone are encased in vein-fillings of barite and quartz.

“I had he good fortune of being on staff from 1960-68, with Dr. Babbidge at the helm during six of those years. I was Administrative Assistant in what was then the Office of Men’s Affairs (Dean of Men’s office). I recall his interest in stone walls and his emphasis on the importance of a solid foundation when building a wall. (An appropriate metaphor). He opined that the foundation needed to be deep enough to be below the frost line.

Until recently, we owned 150 acres in Pomfret, which were crisscrossed by stone walls. (We sold the development rights to the Town of Pomfret). I am sure that few or none of them had foundations – they were the result of land clearing. But the sight of them often reminded me of Homer. He was a role model for me during my years as an administrator in higher education.

Robert E. Miller, President Emeritus (and founding president), Quinebaug Valley Community College”

“A wonderful piece, Dr Thorson! You’ve put a lot more meaning in the stone wall for me. I love our New England stone walls, too. When I see one, I wonder who built that wall and what they were like. The wall has history to it just like an old home that’s on the National Register.

Robert J Gallagher. ’77”

I never hauled a stone for a wall, but enjoyed seeing the walls among the trees, knowing that they had once surrounded famer’s fields. They bordered many off campus roads. They represented a vibrant history, especially near the colonial era house I lived in for a year just off campus. Riding on my motorcycle with a girlfriend, they invited us to pull over and park and traverse into a patch of grass and moss (and manure) they contained for a spring time picnic in the sun. I associate those stone walls and fields with the period of time at UCONN when there were few sidewalks, so walking around campus meant going across wide fields, usually following worn trails, but not always. The stone walls were a tangible reminder of the colonial history of the area and roots of the university. I mowed the lawn of old man Storrs, the last residing member of the family who lived in a house down the road from UCONN which was to be donated to the university after his passing.

“Mr. Thorson,

I enjoyed your article in the alumni magazine. I was a student at UConn from 1966-70 and knew Homer as well as any other student in that time. I revered him and your kind words are much appreciated. I was student government president 1969-70 and worked with him on student-faculty issues often. He was particularly comforting and attentive when my father died in my senior year. Sadly, I have no memory of him ever mentioning stone walls, but I do remember his rather stiff and aristocratic presence; he had two beautiful dogs…boxers as I remember…which he trained meticulously to behave on long daily walks.

As a leader of the anti-Vietnam movement on campus (which led to the semester of no-grades in 1970 when the university was shut down), I can report that Dr. Babbidge was not well-suited to the tumultuous atmosphere in Storrs at that time. He seemed slow to react to changing times, and I’m not surprised that he would retreat into a nostalgia for earlier times represented by stone walls. This is not a criticism; many faculty could not handle students exerting control and questioning authority at all levels. We had many talks during that time and he always was open to advice and counsel. I always liked that he seemed to come from an earlier era when thoughtful scholarship and discussion was it’s own reward. I can’t say he was really friends with any students, but he certainly treated us all with respect as competent young adults. I was very sad to learn of his early passing a few years later.

Anyway, thanks again for the memory. I happen to be a superdelegate to the national democratic convention this year, and much of what is going on in the political arena now reminds me of the late sixties. Hard to believe it’s been 50 years!

Rep. Tim Jerman

5 Sycamore Lane

Essex Jct., Vt 05452”

I’ve seen some beautiful photographs of stone walls in Ireland. What beautiful photos and a wonderful story. I must say, these days, the word wall has a bad taste. I do love the beautiful look of stone walls.