The New

Reparations Math

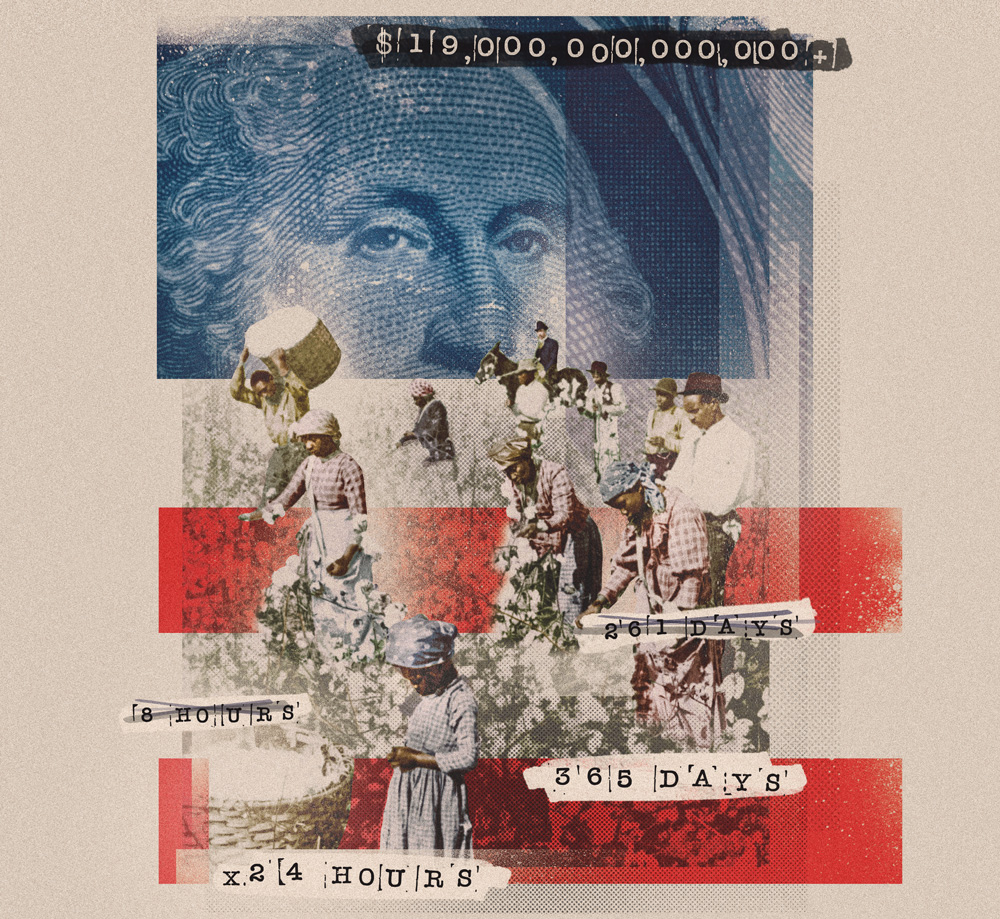

It doesn't add up, thought Thomas Craemer — because slaves didn't work eight-hour days

By Maya A. Moore '19 (CLAS)

Illustrations by Neil Jamieson

H

istorical figures seldom leap off the pages of history books, and we rarely hear their voices outside of those texts. However, professor of public policy Thomas Craemer will tell you that the education he received growing up in postwar Germany prepared him for just such a chance meeting.

Historical figures seldom leap off the pages of history books, and we rarely hear their voices outside of those texts. However, professor of public policy Thomas Craemer will tell you that the education he received growing up in postwar Germany prepared him for just such a chance meeting.

Craemer's parents were children when the war ended. The professor, whose research focuses on race relations and reparations, says that in the immediate postwar era no one wanted to talk about the war or the atrocities that defined the Nazi era. It wasn't until his parents were adults that the curtains were drawn back, and a new wave of interrogation and accountability began.

"Their generation started asking their parents, 'Where were you? What did you do? Why did you not act? Did you know anything?' and so on," says Craemer.

The results were far-reaching. Craemer says his generation had a public-school curriculum that included a lesson about the Holocaust in every subject.

"Except for physical education, every school subject had the Holocaust front and center," Craemer says. "That was tough. You know it's there. You sit in these lectures, you've seen the documentary videos, and you can't help but feel very ashamed. And so I grew up with this desire to be able to express to a Holocaust survivor how I felt about it. But of course, I never thought this would happen."

"The model calculations help us to wrap our minds around the magnitude of the injustice."

Decades later, Craemer's interest in his country's past culminated in the pursuit of a doctorate in political science at the University of Tübingen, Germany.

It was there in his hometown at his parents' apartment that light dinner conversation with friends gave way to a harrowing tale of survivorship. With it came the long-awaited opportunity for Craemer to contend with the barbarity and complicity of his grandparents' generation up close. Craemer sat across the table from the Holocaust survivor at the center of that tale, a man named Mieciu Langer.

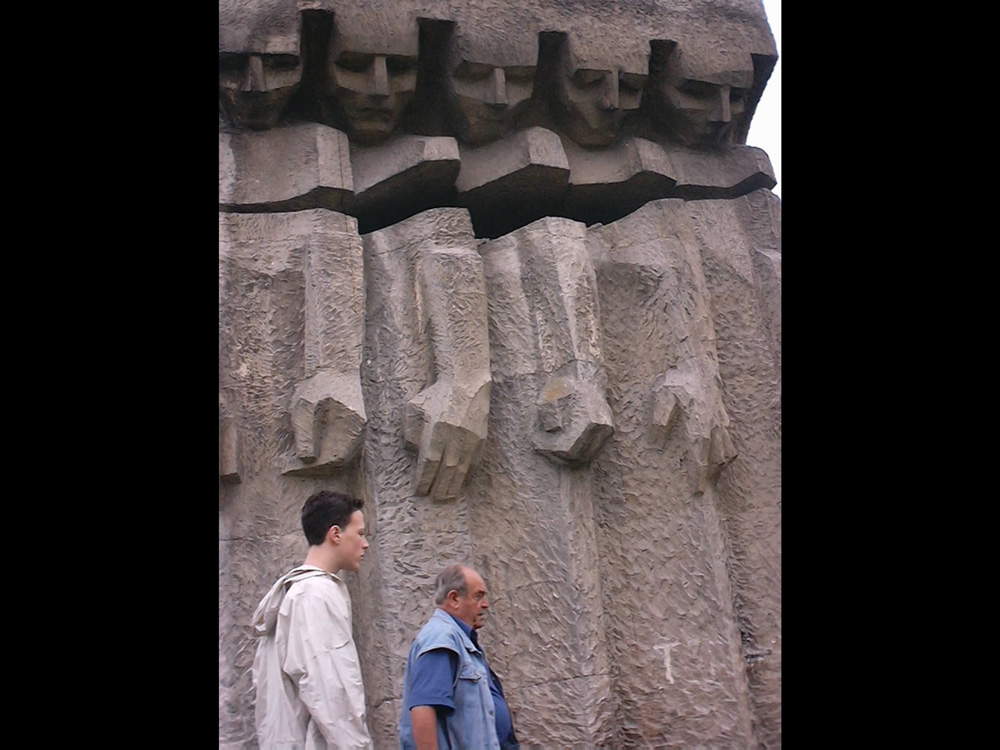

A year later in 2001, Craemer and his parents embarked on a commemorative trip with Langer and Langer's wife and grandson. The group — half German, half Jewish — toured the sites of atrocity from Langer's story. They saw the house in the Krakow ghetto to which Langer and his family were forcibly relocated. Craemer says he took notice of the wall that enclosed the ghetto where the house stood — it looked like gravestones set side by side. Langer led the group to the intersection where the Nazi guards selected him for slave labor — he didn't know it at the time, but those standing across the road from him were sent to the gas chambers.

"And then he showed us the crematory," Craemer says, his voice breaking again. "That was the crematory he was destined for, and he escaped. All of it was so deeply moving. It was kind of a way of making history come to life on a very personal level, and to be able to embrace and connect over it was priceless."

After Langer's passing in 2015, Craemer found out that his friend had been receiving reparation payments from the West German government since the 1970s.

"I'm sure it signaled to him that Germany was taking its legacy seriously and was making amends," says Craemer. "And of course, to me, it was also a significant signal that my country was acknowledging our historical injustices."

Today Craemer resides in the South Bronx with his ball python, Madame Curie, and his African grey parrot Alex. He teaches courses on diversity and inclusion and on race and public policy. Reinvigorated national conversations about reparations have focused new attention on Craemer and his research.

We talked in his UConn Hartford office about the case for reparations through the lens of his life experiences.

Japanese Americans who were victims of WWII internment received an apology and $20,000 reparations from then-president Ronald Reagan. Holocaust survivors received reparations from the German government. What can be gleaned from these historical examples when talking about reparations for slavery in the United States?

I think one thing is, one lesson is, you can never fully repair. So reparations are, in a way, a misnomer. To me, it's a symbolic gesture of contrition — you acknowledge the historical injustice, you vow it'll never happen again, and you give a symbolic token of your sincerity. It's like when you've wronged your neighbor, instead of just saying sorry, you say sorry and bring flowers or a bottle of wine that makes it more meaningful. It's a symbol.

Your research estimates that reparation payments for American slavery would equal $14 trillion — an incredible number. How did you arrive at that figure?

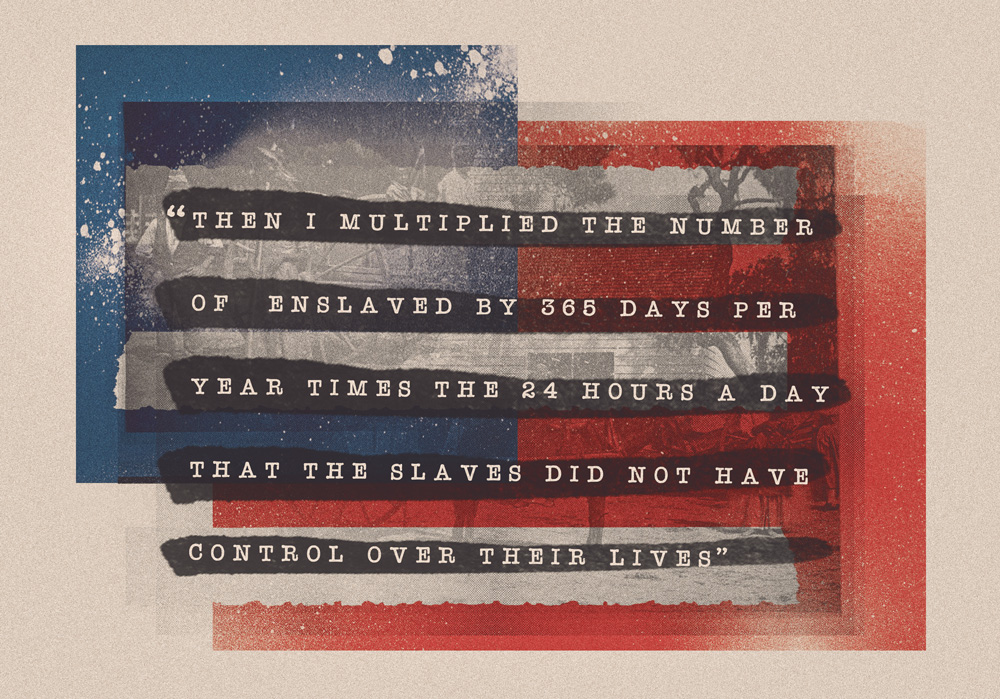

I estimated how many slaves there were in each year that the United States existed, and I excluded colonial slavery. The slave population was counted every 10 years and, for the years in between, I used linear interpolation to estimate the enslaved population. Then I multiplied the number of enslaved by 365 days per year times the 24 hours a day that the slaves did not have control over their lives.

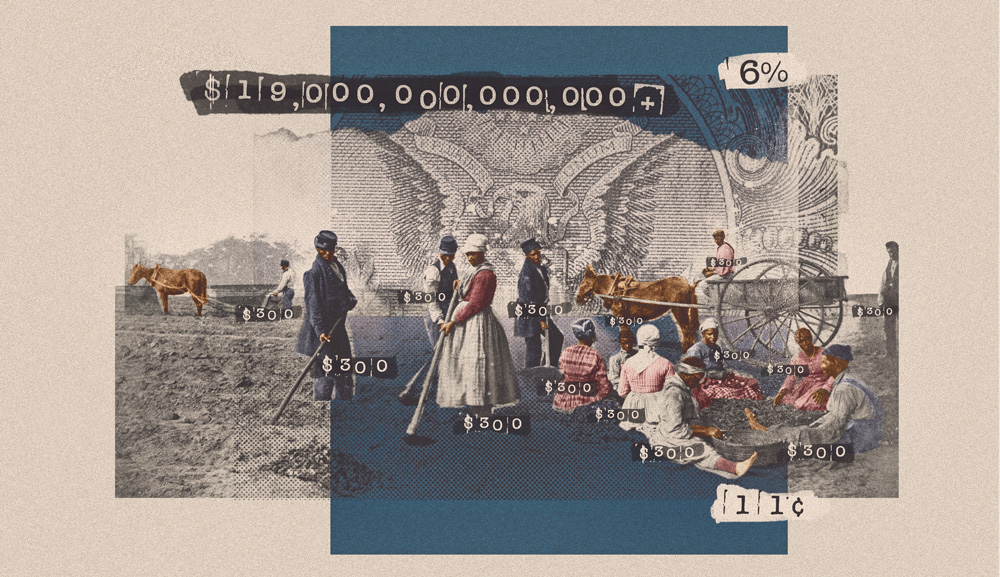

And then I just did the calculation: What would a slave owner have had to pay at the time to have a white person or a free laborer? I found historical wage information about unskilled labor, even though many of the enslaved were skilled. This estimate is conservative because unskilled labor wages were minimal — like 11 cents per hour. I multiplied the number of hours that the enslaved were available to slave owners times the hourly wage. Then I compounded that with a very conservative interest rate of only 3% — that doesn't even make up for inflation. That's how I arrived at the $14 trillion in 2009 dollars.

At the time, it was worth one year of the U.S. GDP. Further compounded to 2018, it's like $18 or $19 trillion. I haven't done the calculation for 2020 yet, but it grows. It's usually roughly one time the U.S. GDP. That's a super conservative estimate. Much more realistic interest rates at the time were 6%. I did the calculation also with 6%, and it just explodes. It gets into the quadrillions.

An April 2019 article in CNN Politics said, "Most formulations have produced numbers from as low as $17 billion to as high as almost $5 trillion." However, the article called your estimate "modest" when compared to others that went as high as $97 trillion. Would you consider your estimate to be modest?

I'm not saying that that should be the amount paid back. For me, the model calculations help us to wrap our minds around the magnitude of the injustice. Capital from American slavery provided the startup loan that the United States then took to have an A-rated economy — and it took that loan by force from African Americans. At some point, there is a need to start paying back the loan.

Reparations have been a big part of the national conversation lately, putting your work in the spotlight. What has that experience been like?

It's a big surprise. I'm glad that it finally has made the mainstream. It's an important topic. When I started this research and initially did public opinion research on it to see how supportive or opposed people were, they were mostly opposed. To know that it gained that much momentum is gratifying.

What suggestions do you have for looking at reparations through a bipartisan lens?

I'm very surprised that it popped up as an issue on the Democratic side because one of the early mainstream proponents of reparations that I can remember is conservative commentator Charles Krauthammer, who was in favor of reparations as a one-time lump sum payment instead of affirmative action. In its structure, reparations are a much more conservative policy because it's about individual responsibility. You have to be a deserving, eligible recipient.

What question do you get asked the most when it comes to reparations?

I get asked about precedents for reparations a lot. Slave owners received reparations for slavery in several instances. One was the Haitian independence debt, where France demanded an indemnity from Haiti for the abolition of slavery so that they could pay off the slave owners that fled from Haiti to France due to the loss of their property. Haiti paid that from 1828, I believe, to 1947 — into the 20th century.

Another instance was when Great Britain abolished slavery in 1833; it paid 40% of the national treasury's spending budget on slavery reparations going to the former owners. It took up loans to finance these reparations payments, and they were paid from 1833 to 2015 — the last of the payments concluded just five years ago!

And then in the United States, when Lincoln abolished slavery in Washington, D.C., the American government paid reparations to the slave owners — about $300 per enslaved.

It's shocking. Former slave owners received reparations from the American government for the abolition of slavery.

So as long as the recipients were white, there was never a question about whether it was too long ago, whether it made any sense, or whether it was too complicated to figure out.

"It's shocking. Former slave owners received reparations from the American Government for the abolition of slavery."

When reparations were paid out to survivors of the Holocaust like Langer, many of the perpetrators were still living. What do you say to the argument that the U.S. shouldn't pay reparations because neither the direct perpetrators nor survivors are still alive?

The institutions are still alive. The federal government is still alive, and the federal government allowed slavery to exist. It could have quickly abolished it. Many Northern states did. That shows that it was possible at the time. The institutions still exist; companies still exist; the capital of companies still exists.

Slavery provided the startup capital for the U.S. economies. That capital is still alive, and it grows exponentially every year, of course, in more and more diffused hands, so you don't see it accumulated anywhere. In private hands, it has decreased, but as a sum, that capital still grows, and it grows exponentially.

What would you say to Americans who may be reluctant to contend with the legacy of slavery in America because of how heinous it was and how deep-rooted it remains? How can this translate to understanding policy proposals like reparations?

We were all very proud of claiming the legacy of our forefathers. I'm speaking as an American — I'm very proud of the American Revolution, of the founding fathers, of the democratic experiment that they started, of the experiment of human equality — although it was flawed at the time, the ideas were great.

We're all very proud of that, and we accepted that positive legacy as if we had invented it ourselves. Nobody alive today was alive when the revolution took place, so does that mean we shouldn't have freedom of speech or we shouldn't have religious freedom? No, we claim those things as our birthright because we inherited them.

The problem is we also inherited the legacies of slavery, the racial wealth gap, and the double standards that the founding fathers had. So, we can love our founding fathers, but we can also be critical of them.

And that's kind of what I had to learn growing up — being angry at my grandparents and ashamed of them, and at the same time loving them as people. And both work at the same time. You can be both proud and ashamed of your forefathers for different things.

What are you working on now?

I feel very honored to be part of the reparations planning committee, led by professor William Darity of Duke University. Darity put together a large group of experts, mostly African Americans, who are researching various aspects of reparations. We are working on a report that should come out this year, talking about how to estimate, for example, the contributing factors to the wealth gap.

There are other aspects of the report as well: What should the design of a reparations policy be? What role does genealogy play? The report looks not only at slavery but also at Jim Crow discrimination, New Deal discrimination, discrimination during World War II, and afterward with the GI Bill. The report also considers post"“civil rights discrimination and looks at how all that affected African Americans living today.

You spoke about growing up in a culture of accountability and contending with your country's past at a young age. Why was that important?

It instilled a curiosity about history and about what went on in my generation. That curiosity took on a life of its own, and we started researching our hometown and looking into which stores and establishments had belonged to Jewish families.

Now people do the research and put what's called Stolpersteine or "stumbling blocks" into the pavement. These are little bronze cobblestones that have inscriptions on them with the name of the family that owned a given property and a brief story of what happened to them in the Holocaust. You can see this all over Germany.

The Stolpersteine initiative is a bottom-up initiative. So it led to a culture of actively looking for documentaries and historical accounts and discussing them actively. There was a culture of ongoing commemoration that goes beyond just checking the box and saying, "You have reparations paid."

In the Moment

Maya A. Moore earned her UConn degree in journalism and political science in December 2019 and was the CT Mirror's 2019 Emma Bowen Foundation intern. Moore interviewed Professor Craemer for this story in his Hartford office the week before all campuses closed:

Before this experience, my work-from-home process often consisted of interrupting chatter from my roommates in the next room or negotiating for the best dimly lit table at the nearest Starbucks. Covid-19 has laid siege to our lives, our routines, and our selves so by no surprise, the circumstances under which I was able to write this story were unusual and, at times, both arresting and devastating. The week before I interviewed Thomas

Craemer my paternal grandmother passed away, and the plans we had for her Los Angeles send-off slipped away as the country began to lock down. In between periods of transcribing audio from the interview were tense family meetings that ultimately led to the decision to have only my father and his six siblings attend the burial. After completing my first draft, I laid out the clothes I would wear the next day to watch my grandmother's funeral via FaceTime. Over a matter of days, the tone of the emails from the corporate heads of my "bread and butter" retail job swung from unrealistic optimism to discrete panic, and I've now joined a growing population of Americans in unemployment limbo.

As my story underwent its first edit, we received news that my father had tested positive for coronavirus after arriving back in Connecticut. My father's symptoms have finally plateaued along with the gut-wrenching worry my family and I have experienced. Now, like everyone else, all we can do is wait. Many people are trying to retain their routines, their sanity, and their humanity. For me, this story and this process lent itself to that endeavor.

Maya, this was so powerful. It was well written and heartfelt. Even through the midst of everything, you pushed through to share an eye opening view. Thank you and well done!

How does the math work for example assuming 6% interest as a constant is erroneous, who will pay the reparations , everyone or just those who were slaveowners, what value will be given for those who fought in the civil war. Come on now, lets heal the ancient wounds and move one as a nation.

I do not believe that monetary reparations are due. Has anyone counted the cost of LBJ’s programs, made specifically to rebalance Black life. Caucasians and Asians denied a college entrance for the place of another minority? What is the cost of life lost? About 360, 000 Northern soldiers died for that war that did emancipate the Black slaves. Reparations WERE made for the sin of slavery.

Why do some say it is not enough?

I will concur with Mr. Cote’s remarks above. Having willingly complied with the merits and benefits of affirmative action quotas in hiring and promotion selection during my management career, I, too, feel “reparations” have been paid to many. (I won’t even go down the rabbit hole of who should get them.) Noted Black intellectuals have stated these atonement gestures communicate “if we don’t help you, you can’t make it.”

What is more, I will not join the “atonement” bandwagon driven by the BLM-White guilt movement (with untold support from our “institutions of higher learning,” an increasingly unearned title these days). While sympathizers (Dr. Craemer, et al) have reparations (the solution) looking for a justification, the parallels with the Holocaust Jewish population and the Japanese internment cohort are a stretch in the least, taking colonial America out of context for the benefit of a rationale. Slave trade pre-existed colonial America, with White slaves being part of the trade business as much as Blacks, and Black slave owners heavily in the mix of things. The Middle East and Africa, not Europe or the Americas, were in the van. Whether or not one is understanding of the morality and ethical choices of the period–different from ours, of course–it was, unfortunately for our 20-20 hindsight, a business. Blacks, Whites, Moors, Arabs–all practiced slave trade. Today, we reflect and understand slavery was wrong. But to attempt to rewrite history–and correct some fictitious ledger sheet–in light of our current sentiments disrespects history and the story it is charged with telling. What us more, with 80% of Black Americans (according to the Census) experiencing degrees of economic prosperity, the country’s emphasis should continue to be creating opportunity–not handouts– for the 20%…and the millions of White Americans struggling as well. To paraphrase Robert Frost, “My UConn is hard to see.”

I close with a well-respected Black American’s observation:

“Have we reached the ultimate stage of absurdity when some people are held responsible for things that happened before they were born, while other people are not held responsible for what they, themselves, are doing (or not doing)* today?”–Thomas Sowell

This reparations thing is getting to be a bit much.

I helped a friend establish the provenance of an ancestor’s Civil War weapons, uniform, and paperwork. That gentleman enlisted in 1864, AFTER the Emancipation Proclamation changed the focus of the war to abolition of slavery.

How does the math account for that?

My family arrived here from Italy in 1905. Far from being slave owners, they were more likely targets of discrimination. I also never owned slaves and never, in any significant way, discriminated against any race. I have no White, liberal guilt. The idea of reparations is ill-conceived, fraught with peril and would ultimately be destructive to All Americans. Germany paid reparations to Jewish survivors and immediate families of those lost. They were also paid to Japanese Americans and immediate families interred, although one could easily argue that in a time of national emergency, like a world war, it was not unreasonable. How is it rational or justified to pay taxpayer dollars to those five, six generations or more removed from those who suffered? Again, White liberal guilt is driving this and blacks are salivating over another free payout from the government. I could go on at length since there are so many valid arguments against this. Further, the very idea of pursuing ‘revisionist history’ by demonizing people who lived more than five hundred years ago and judging them by today’s standards is foolish and also very destructive. In another post, it was pointed out that one goal, not the only or even primary goal, of the American Civil War ended slavery. That was the right thing to do of course….case closed! Prior to that correction we have to accept that by our modern standards, yes it was abhorrent, but it was Legal! In 150 years will we be vilified, statues torn down and other indignities leveled because of some behavior we find socially acceptable? How ridiculous this all is. Lastly, Americans are armed to the teeth. If reparations are paid I predict and fear that it may lead to a severe and violent reaction.

How can opinions and comments be ‘approved?’ This is censorship!!! Either post our comments as they are written or do not ask for opinions!!!!!! Is this a free and open exchange of ideas and thoughts or not?

Posts must be “approved” because many are spam. We encourage healthy dialogue and opinions. Thank you for sharing yours.

Thank you for this thought provoking article. I was struck by the dollar reparation estimates to repay for the injustices of slavery and learning that slaveowners were paid reparations. As a Jesuit high school educator, I feel that enlightening each student (and American) with these numbers and historical facts that are, unfortunately, left out of history books, is vital to any form of healing. Thomas Cramer’s walk with Mieciu Langer is surely the best example on how to begin the process.

Ms. Moore, thank you for undertaking this interview, and for sharing the circumstances of your life at the time you did it. Best wishes in these turbulent times.

The information and opinions Professor Craemer expressed are sure to raise hackles, as is evident in the discussion. And, he points out that the purpose of the calculation, in the trillions of dollars, is for emphasizing the magnitude of the injustice, the unrecompensed labor of generations of enslaved people that built the U.S. economy, rather than demanding those trillions of dollars be repaid in cash, now. As is easily ascertained, that injustice continued long past emancipation and Reconstruction, compounded through convict leasing, Jim Crow, redlining, etc.

My family arrived in the United States in the early 20th century and experienced anti-Semitism in various forms here, yet, by the second generation, benefited by the very unequal distribution of benefits to white and African American veterans of WWII. Irish and Italians, immigrants from Europe, were discriminated against initially but gradually and eventually assimilated into whiteness, too, and got a leg up. Black and brown people have not, despite a few decades of affirmative action (which mostly benefited white women). Despite many years at elite educational institutions, I was not taught the basic facts about American systemic racism, though I was vividly educated when young about the Nazi era, by teachers who were survivors of the camps. It’s crucial that we learn the truth of our history, because it shapes our present and future–the present and future of all of us.

My husband is the UConn graduate (1964) in our family, but I am the faithful reader of your magazine, always finding informative and interesting stories. The Summer 2020 issue did not fail me: FLASHBACK to Oct 15, 1969 Student Protest brought tears to my eyes. In 1969 the photographer, student Howard Goldbaum, wrote of the coalition of antiwar AND Black Power protests. I ask your readers to research the results of the 1968 Kerner Commission on racial disorder and social division to see some of the roots of today’s BLM movement: “This is our conclusion: Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white–separate and unequal.” The commission’s recommendations are a direct echo of BLM demands for change today. Perhaps your magazine could include a piece about this in your Fall 2020 issue. Elizabeth Cooke

As an ADOS woman who is descended from the people who built this country for free I encourage the boo-hooers to read K. Mullen and Dr. Darity’s book called From Here to Equality. I also could care less about the immigrant story of your family. We are not descended from immigrants who CHOSE to come to this country. Your opinions mean nothing because this is a federal debt that is owed to American Descendants of Slavery. #cutthecheck #purereparationsnow

The negative repercussions from slavery are more than just the monetary wealth that this country and europe accrued from FREE slave labor. The math speaks for itself. The social, financial, health and educational destruction of black people through reconstruction, the black codes, Jim crow laws, redlining, voter suppression, the prison industrial complex etc. all contributed to our condition in this country. Reparations also addresses and demands justice for the wrongs done to us over hundreds of years and allowed by the U.S. government, pre and post slavery. If you’re against justice and repair for damages done, then you don’t believe in the basis of this country and you shouldn’t be here. Everything we seek through reparations have been done before, for others, here and around the globe. There’s plenty of data available to substantiate a reparations claim against the U.S. for the ancestors of the once enslaved people of the U. S. I submit that people’s REAL problem with reparations is not the money (this country spends billions ANNUALLY in foreign aid alone, with no outcry), it’s not that they don’t know what justice is (they know when THEY’VE been wronged) and it’s certainly not that american history escapes them (there’s TOO MUCH recorded history here for that excuse) I submit their problem is with the people making the claim, which is another example of the damage black people in the U.S. suffer from our humanity being destroyed to the degree that people believe we don’t deserve justice or repair for damages past and present. Remember, the slave owners received more reparations than the enslaved. And for the record we did NOT immigrate here, so most immigrants and their ancestors probably would not respect or understand that claim. Justice and repair.

Thanks for this. I was looking for something to give one of my students about reparations. Fascinating story about a man with some very interesting and rigorous ideas. And I like the way you write. Any more of these stories coming? – PG