"It's beautiful to me," says plant pathologist Abby Beissinger of specimens that would elicit "Oooh, gross!" sounds from 99% of the population. Commercial growers and home gardeners bring or mail her samples of plants they suspect are sick with pests or disease. She often goes microscopic, drilling down to a cellular level to make a diagnosis.

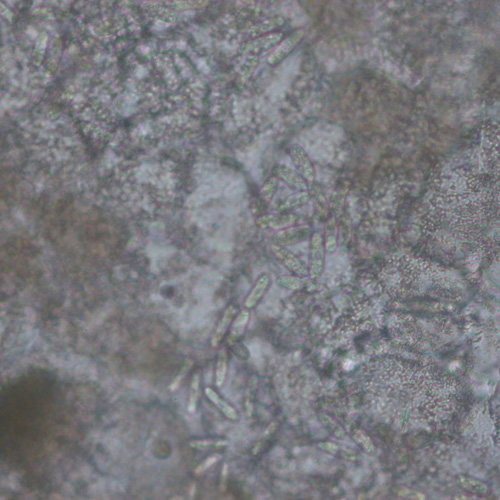

"Seeing what emerges is super exciting," she says. "And here's why. Each pathogen looks so different. With fungal spores, it's not that one's a circle and one's a zigzag; one will look like a tadpole, and one looks like a crystal ball. It's this whole world we don't have access to unless we have bionic eyeballs — or a microscope."

Related Links

Admittedly "exciting" and "beautiful" are not the first words a farmer receiving a diagnosis might utter. But it's important to know what is ailing their plants so they can remedy it. Recently, Beissinger, who runs the Plant Diagnostic Lab in the Ratcliffe Hicks building at Storrs, combed through some 500 leek samples looking for pupa she then raised in petri dishes. In so doing, she helped confirm that the commercial farmer who sent the leeks had one of the first known cases of allium leafminer in Connecticut. "Allium leafminer can completely decimate a leek field," says Beissinger. So knowing it's here is critical for controlling it this season and preparing for next.

The Lab collaborates with UConn's Home and Garden Education Center (HGEC); both are part of the College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources Extension program. You don't need commercial crops or even live specimens to take advantage of the Lab's expertise. As with so much else these days, Beissinger's work is increasingly digital — telemedicine for plants. As of mid-May, she'd received 120 digital samples, nearly double last year's tally. The shift is not solely a result of coronavirus.

"I've been really trying to ramp up my social media content for the Lab. It sparks people's minds. They'll think, 'Oh, I'm seeing something like that in my garden,' or 'Oh, I've always wondered about this.'" Which plays right into Beissinger's hand. "One of my main goals is to help people see how really interconnected we are to plants."

Sleuthing 101

Beissinger always felt that connection to some extent — growing up outside Chicago, she planted impatiens with her mom. But it wasn't until the end of her senior year at University of Wisconsin"“Madison that she found her pathological calling. Needing one more science class to graduate, the anthropology major who had also been drawn to environmental agriculture studies chose "Plants, People, and Parasites."

"It was just a 100 course, a gen-ed, but I was absolutely floored. It was just so thrilling to me." She went to grad school for plant pathology. "You could say it was a highly uninformed decision, but I just had this gut feeling that there would be a need for understanding how plant diseases affect people."

With people spending so much more time at home, demand for the Lab and HGEC services has been growing. "It's just this massive resource for home gardeners," says Beissinger. "What kind of tomato do you want to grow? What soil does your rhododendron need?" As for her Lab, you can snail mail or email to submit samples. For $20, you get testing, microscope photos, and instructions on what to do. And digital diagnoses are free.

Beissinger has some advice for all the people getting into gardening this summer. The greenhouse and nursery industry in Connecticut had to completely redo business models, going to curbside delivery, at their busiest time of year. She suggests finding garden centers in your area — you'll help the local economy and find people who really know their plants.

By lisa stiepock

Photo above by Max Kelley

Photos below by Abby Beissinger

Below: The plant detective's photos of bitter rot disease on an apple. From left: the naked eye view; views of fungal fruiting bodies where spores are emitted; a spore within the tissue viewed under a compound microscope; and spores free floating on a microscope slide.

Leave a Reply